Introduction

The Asia-Pacific region is entering the period of heightened uncertainty, driven by rising protectionism, intensifying geopolitics, and increased use of security exceptions to impose tariffs and non-tariff barriers. Against this backdrop, key questions arise: “What are the economic growth implications?”, “How are governments likely to respond, and what policies will they pursue?”, and “Which regional frameworks or institutions will they simultaneously leverage to advance economic cooperation?”

To shed light on these questions, the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC) conducted an expert opinion survey of more than 500 individuals from government, business, academic/thinktank, civil society, and media across 24 economies from June to August 2025. The survey showcases their views on several topics, including growth prospects, top 5 risks to growth, governments’ responses to protectionist measures, and the top priorities for APEC Leaders (see Annex A for details). Findings in Chapter 1 are presented both in aggregate and with breakdowns by subregion, affiliation, and age group where appropriate, offering additional insights for policymakers as they shape future strategies.

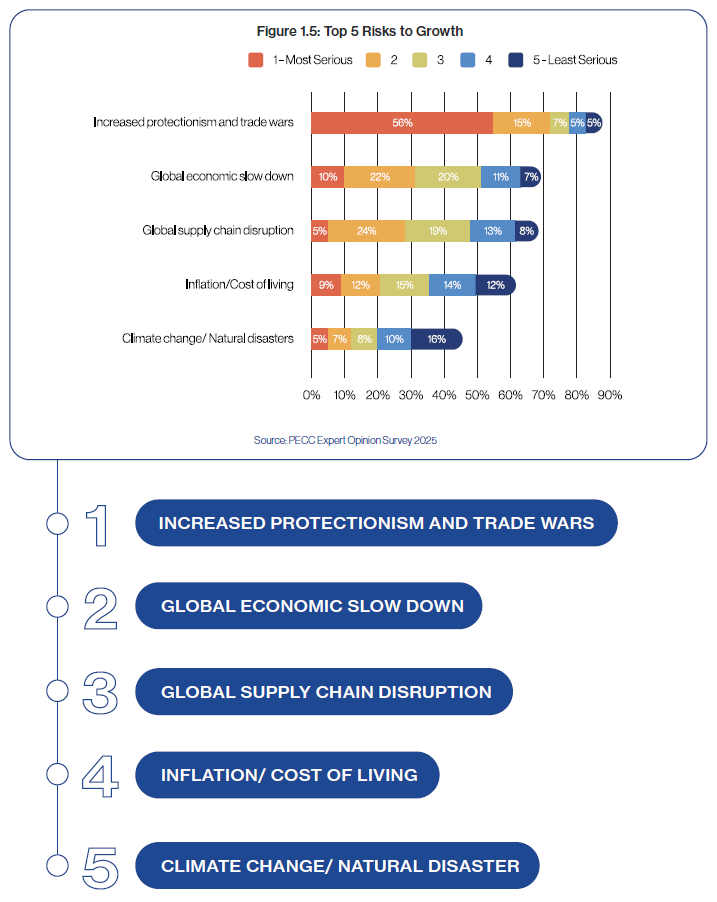

The findings reveal widespread concern about the global economy, with many respondents expecting it to be weaker or much weaker in the next few years. “Increased protectionism and trade wars” emerges as the most serious risk to their economy’s growth. Survey trends over recent years show a growing number of participants view this issue as a risk to growth. Other risks such as global supply chain disruption, inflation, and climate change are also cited, but with a more moderate level of concern.

At the same time, respondents anticipate governments pursuing varied approaches to respond to protectionism, adding complexity to the future of the international economic order. Amidst rising protectionism, some respondents believe the Asia-Pacific region will emerge stronger or much stronger in the next few years. Increased protectionism may serve as an impetus for some groupings of regional economies within APEC to deepen their trade ties, despite such agreements being regarded by many as the “second best option” relative to broader regional agreements.

Amidst mounting pressures on the rules-based trading system, respondents express hope for multilateral cooperation under Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), the World Trade Organization (WTO), and other regional arrangements. Survey respondents broadly agree that the highest priority for APEC Leaders when they meet in the Republic of Korea this fall should be to take collective action to lessen the risks caused by rising protectionism and trade wars. Other priorities should include: lowering geopolitical tensions, boosting supply chain resilience and efficiency, facilitating the adoption of emerging technologies and AI and managing risks arising from these technologies, and supporting the multilateral trading system. Because its initiatives are voluntary and non-binding, APEC has been able to build a strong track record of generating ideas and initiatives that feed into broader global discussions on topics – ranging from supply chain connectivity and structural reform to regulatory practices and the digital economy. APEC has also been constructive in its support for the WTO: in their 2025 Joint Statement, the APEC Ministers Responsible for Trade reaffirmed the WTO’s importance in advancing international trade cooperation, recognized its rules as an essential part of the global trading system, and pledged to contribute to the success of the 14th WTO Ministerial Conference (MC14) in 2026.

Looking ahead, the international economic landscape will remain challenging. This environment renders APEC’s principles of open regionalism and consensus-building more important than ever. By championing these values, APEC can help prepare the region for turbulent times and foster a more cooperative and integrated economic future.

Regional Economic Outlook

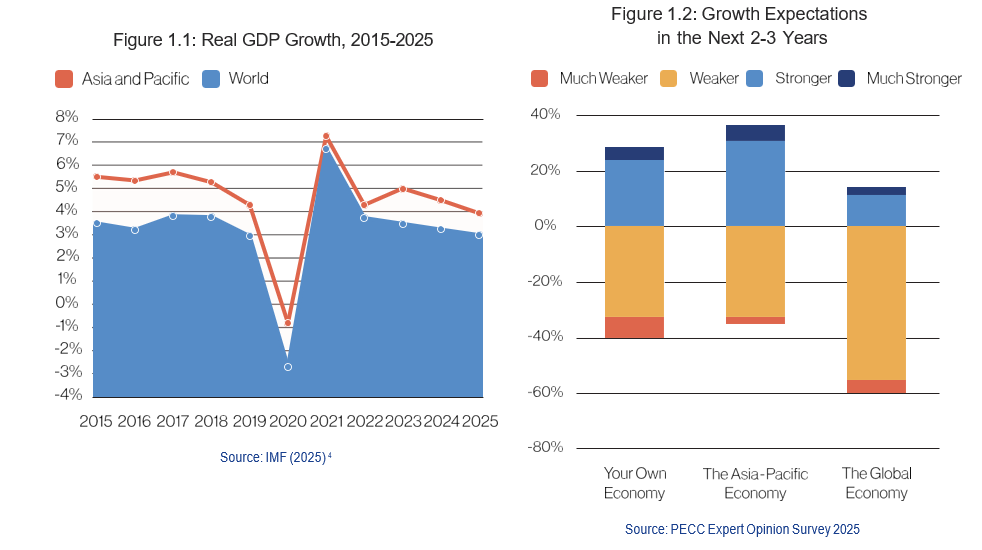

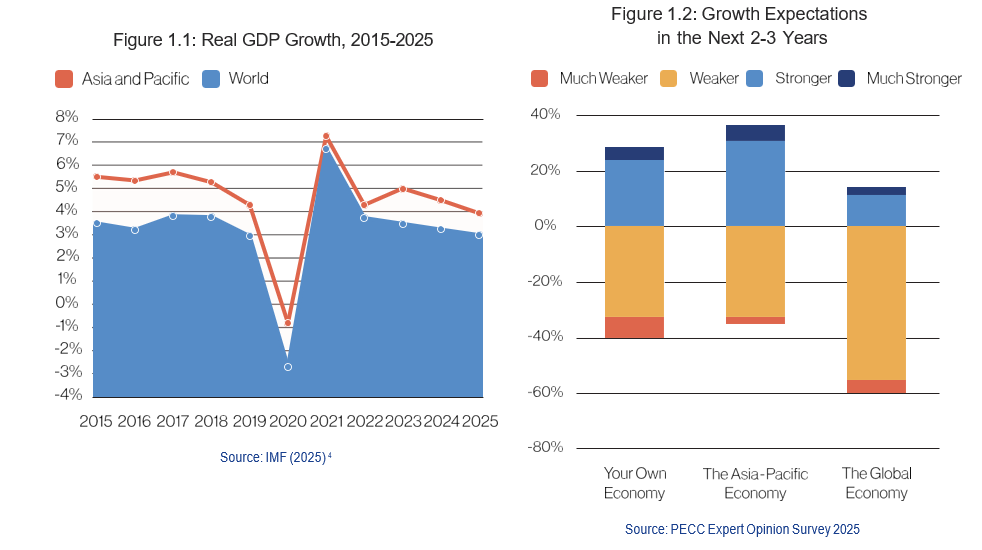

Global economic conditions are entering a period of heightened uncertainty. Governments around the world are reassessing their policy priorities against the backdrop of escalating trade tensions and volatile financial markets. Consequently, growth prospects have been adjusted down by various international organizations. Regarding the world economic outlook, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in July lowered its projection to 3.0%, a decrease from its January estimate of 3.3%.2 While the Asia-Pacific expected growth rate exceeds the global average, Asia-Pacific’s expected real growth rate is still below the pre-covid-19 years (Figure 1.1). The downward reassessment of growth includes developing economies as well, since the Asian Development Bank has also lowered its 2025 growth assumptions for Developing Asia, from 4.9% to 4.7%.3

These projections are echoed in the PECC expert opinion survey which shows that the majority of respondents believe that economic growth will slow over the next few years (Figure 1.2). Respondents generally believe, however, that their own economies and the Asia-Pacific as a whole will perform better than global economy. While 60% of them anticipate the global economy will be “much weaker” or “weaker” in the next few years, only 36% hold the same pessi- mistic view for the Asia-Pacific region and 40% for their own economies.

2 International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2025). World Economic Outlook, July.

3 Asian Development Bank (ADB) (2025). Asian Development Outlook, April.

4 IMF (2025). World Economic Outlook Database. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/NGDP_RPCH@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD

Several factors may explain these findings. For one thing, respondents likely anticipate that the positive growth impact from the frontloading of exports in advance of the anticipated US tariffs during the first half of 2025 will likely be unwound during the second half and beyond. Geopolitical tensions and conflicts, increased use of national security to justify protectionism, and new industrial policies further exacerbate market uncertainty and weaken global demand. No one can predict how the interactions among economies will transpire. Some analysts foresee collaboration on specific areas while others anticipate a virtual collapse of international trading system or something in between, a more fragmented version characterized by smaller and exclusive trading blocs.

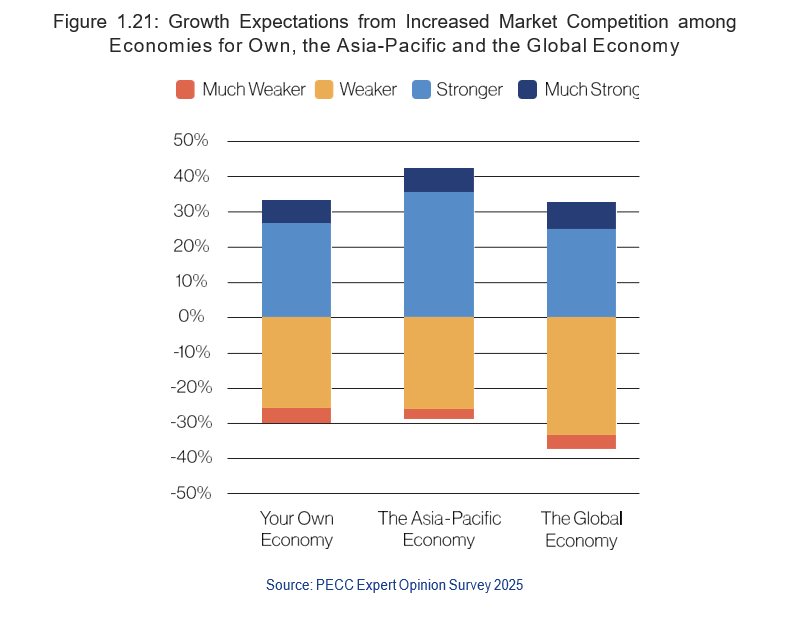

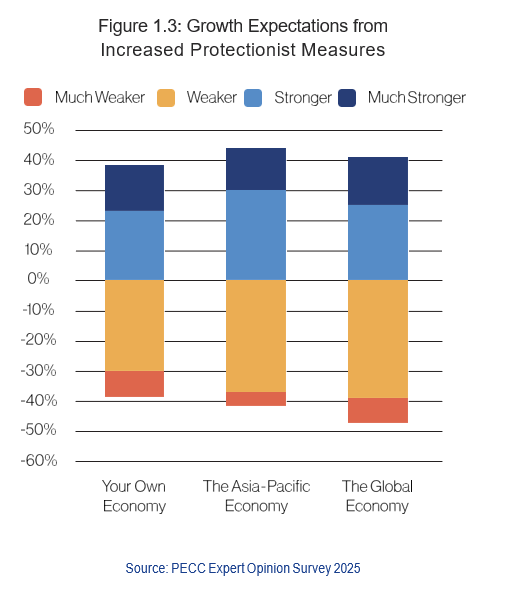

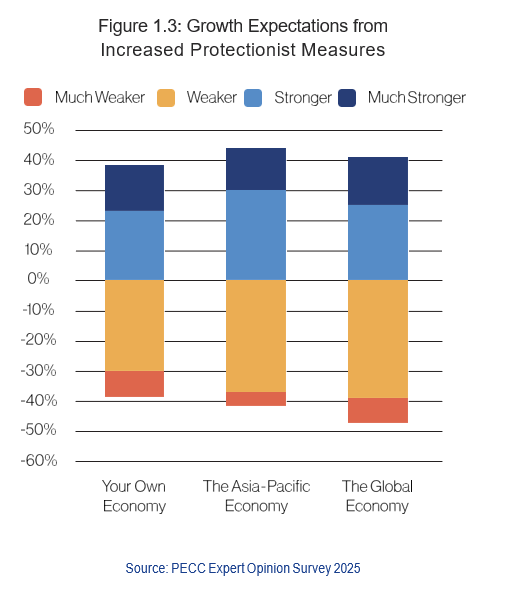

The effects of increased protectionism loom large on the prospects for future growth. According to the PECC survey, around 38% of participants believe increased protectionism will make their own economy grow “much weaker” or “weaker” in the next 2-3 years (Figure 1.3). About 42%, and 46% of them respectively see protectionism as a cause of the “much weaker” or “weaker” growth of the Asia-Pacific and global economy during the same period.

Even amidst rising protectionism, about 44% of respondents believe the Asia-Pacific’s GDP will expand in the next few years (Figure 1.3). Increased protectionism by some economies may act as the catalyst for regional econo- mies to deepen their trade relations among themselves, even though regional trade deals are considered the “second best option”.

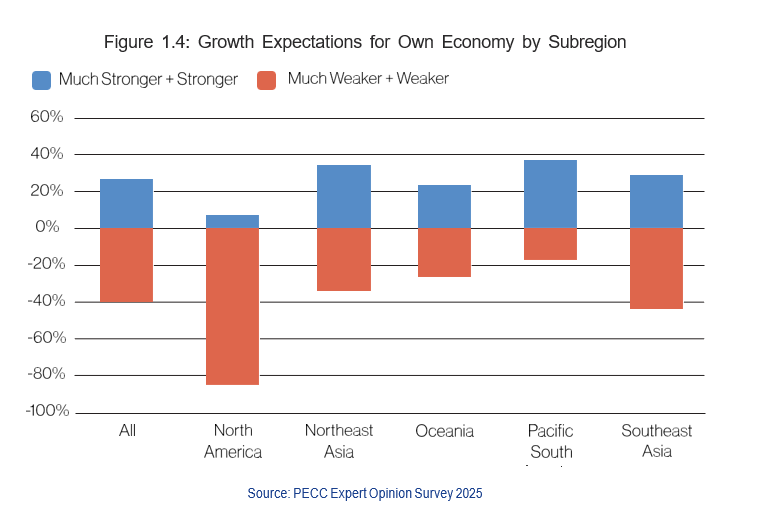

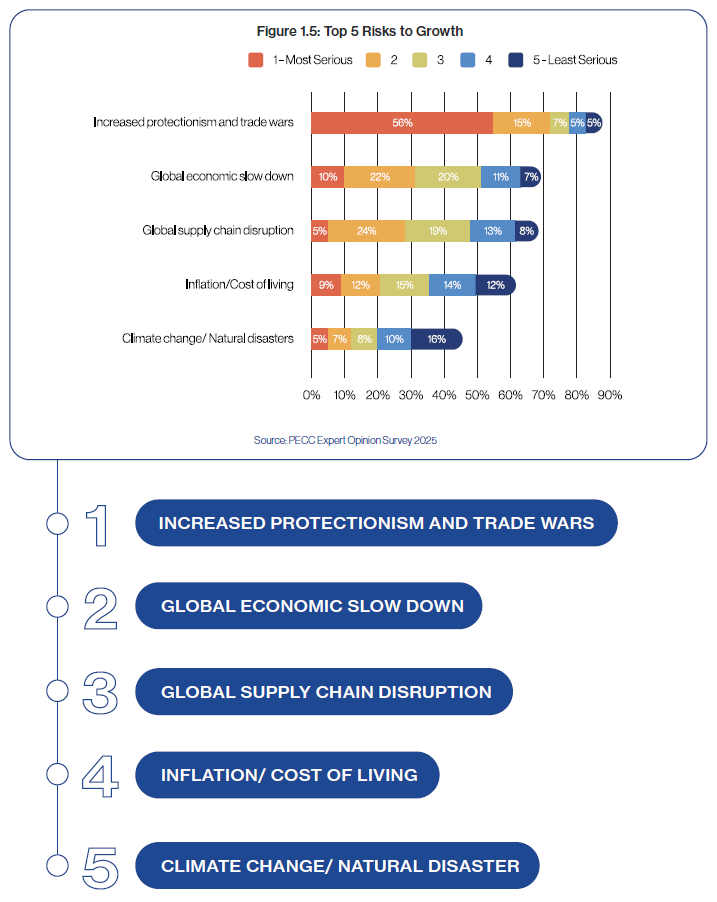

Regarding subregional variations, the individuals from North America are the most pessimistic about their own economic growth, with 85% of them expecting growth to be “much weaker” or “weaker” in the next few years (Figure 1.4).

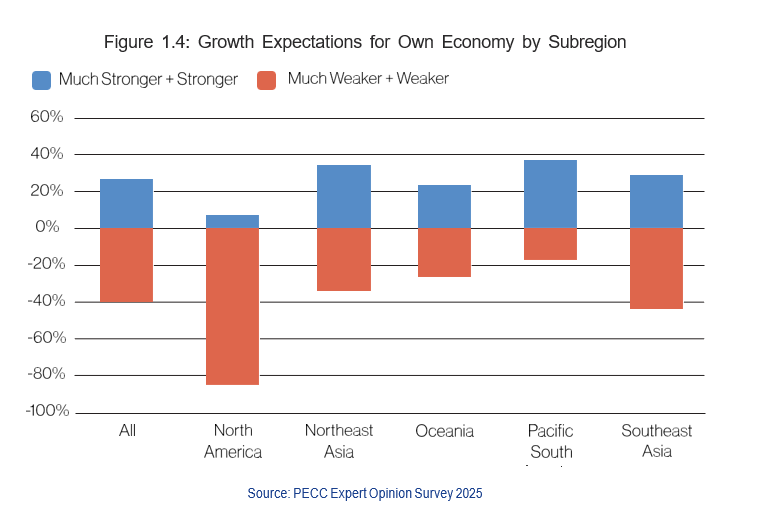

Top 5 Risks to Growth

The PECC survey shows that “increased protectionism and trade wars” emerges as the biggest risk to growth (Figure 1.5). 56% of participants cite it as the “most serious” risk. The sentiment is mainly caused by the Trump Administration’s “America First Trade Policy” which is seen by many economies as exhibiting a strong protectionist stance. The initiative leverages tariffs to address the US merchandise trade imbalances, protect and stimulate its domestic industries, and bring out-sourced jobs home. The policy has become one of the defining features of the current trade landscape. In the end of August 2025, the US average effective tariffs on the imports from the rest of the world stood at 17.41%, the highest since 1935.6 Higher duties were applied to specific products such as aluminum, steel, and copper, generally, and applied to products from particular economies.

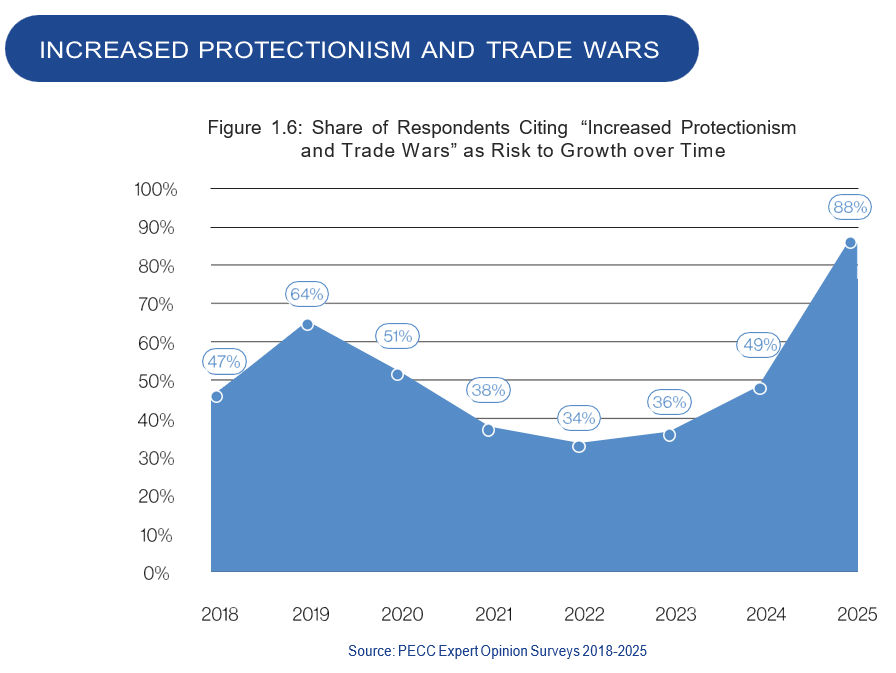

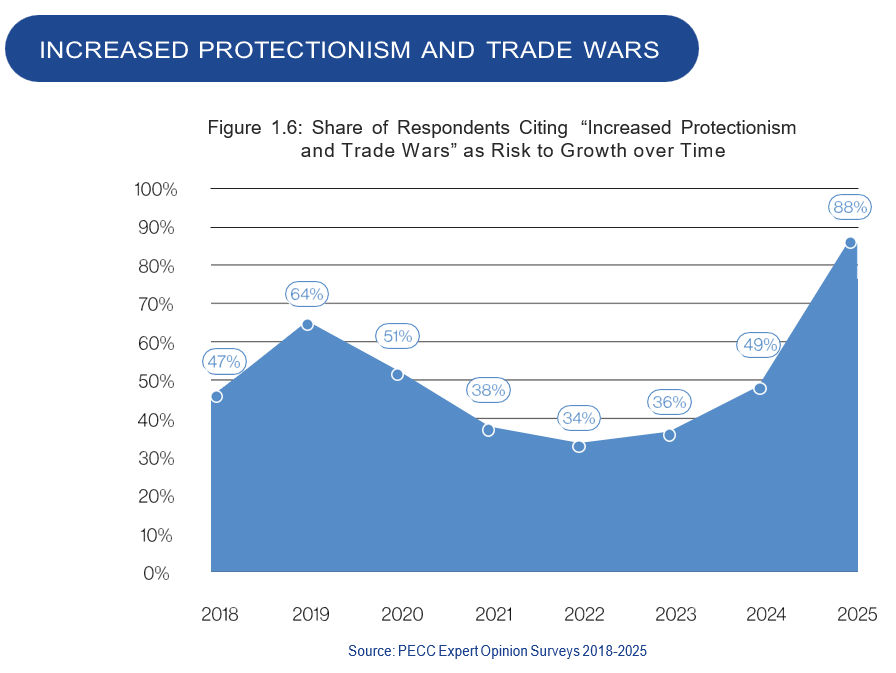

The PECC survey over the years has included “increased protectionism and trade wars” as one of the choices for respondents to select as a risk to growth. The longitudinal comparison reveals that the share of respondents that consider this risk to be among the top five risks to growth has risen sharply in recent years (Figure 1.6).

6 This percentage is a pre-substitution one which is before US consumers and businesses change their behaviors in response to the tariffs. For details, see The Budget Lab (2025). “State of U.S. Tariffs: September 4, 2025”, Yale University.

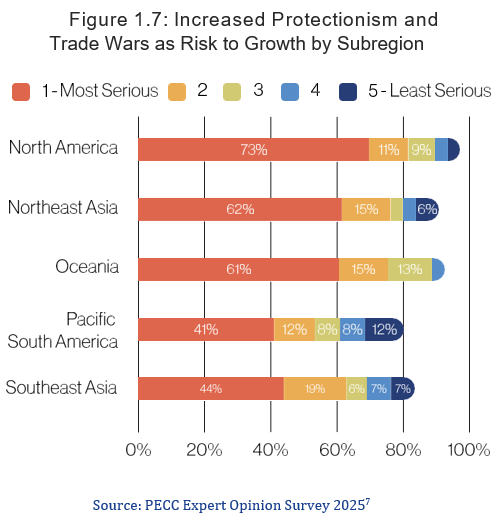

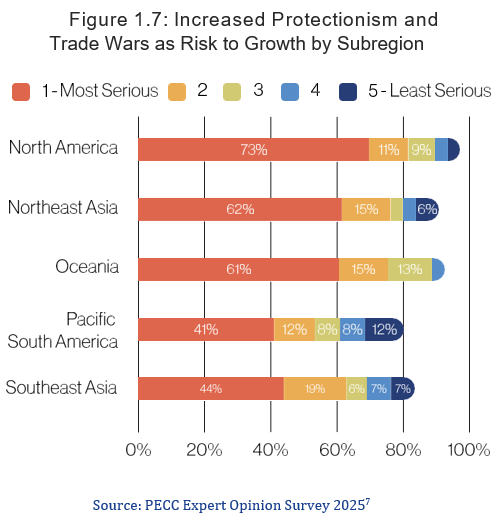

Different subregions possess divergent perspectives (Figure 1.7). For instance, 73% of respondents from North America choose “increased protectionism and trade wars” as their “most serious risk”. This may be because this subregion houses the economies most exposed to the US market. For example, Mexico’s and Canada’s goods exports to the US account for 28% and 19% of their GDP respectively. Also, 62% of survey subjects from Northeast Asia and 61% from Oceania consider the issue as their “most serious risk”, indicating serious concerns. This may be because the US remains one of their major trading partners.

Different subregions possess divergent perspectives (Figure 1.7). For instance, 73% of respondents from North America choose “increased protectionism and trade wars” as their “most serious risk”. This may be because this subregion houses the economies most exposed to the US market. For example, Mexico’s and Canada’s goods exports to the US account for 28% and 19% of their GDP respectively. Also, 62% of survey subjects from Northeast Asia and 61% from Oceania consider the issue as their “most serious risk”, indicating serious concerns. This may be because the US remains one of their major trading partners.

In contrast, only 44% of respondents from Southeast Asia and 41% from Pacific South America pick the issue as “the most serious risk”. Some of them have the US among their biggest trading partners. For example, Vietnam’s goods exports to the US account for 30% of its GDP. Despite the exposure, these economies are advancing their own cooperation and integration under entities such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the Pacific Alliance. Such mechanisms may provide them with more opportunities to diversify or leverage subregional markets amidst rising protectionism.

APEC initiatives promote a free, open, and rules-based trading system. The Putrajaya Vision 2040 aims to build an “open, dynamic, resilient and peaceful Asia-Pacific community by 2040,” and the Aotearoa Plan of Action outlines specific policy measures and prioritizes strengthening the multilateral trading system with the WTO at its core. Moreover, APEC economies are advancing the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) agenda through the Ichma Statement and FTAAP Agenda Work Plan. PECC has also advanced regional thinking on inclusive growth and economic cooperation in the region through its Signature Project on FTAAP. 8

7 Percentages are shown if they are 5% or greater.

8 PECC Signature Project on “FTAAP: Pathways to Prosperity” focuses on Services and Good Regulatory Practice, Professional Services and Mutual Recognition, and Trade and Climate Change. For details, see https://www.pecc.org/pecc/204-issues/957-ftaap-pathways-to-prosperity

GLOBAL ECONOMIC SLOW DOWN

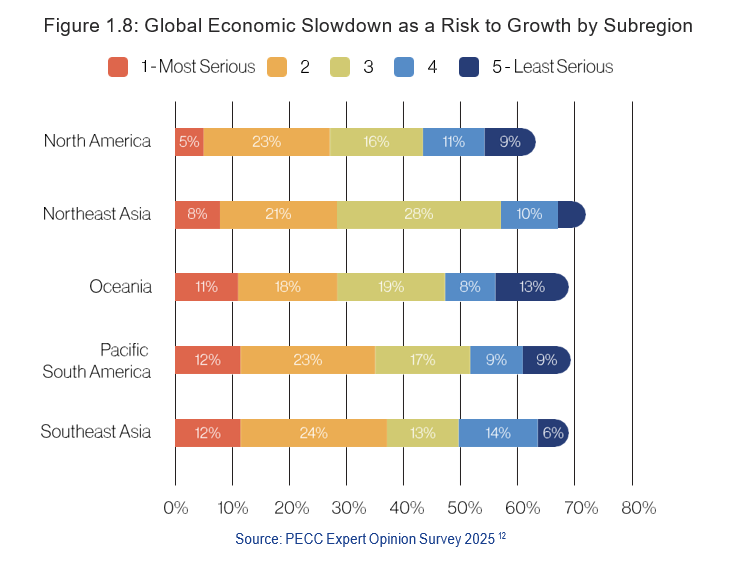

A “global economic slowdown” is cited the second biggest risk to the growth of individual economies, underscoring the transmission channels through which weaker global demand affects exports and investment (Figure 1.5). As mentioned in the Introduction, global output is expected to decelerate. Key drivers of this perception include increased number of trade barriers, economic policy unpredictability, and geopolitical dynamics. The World Bank’s report attributed its downgraded growth projections to a sharp rise in trade restrictions and policy- related unpredictability.9 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) links the economic slowdown to protectionism and economic policy uncertainty.10

In a similar vein, the IMF highlights that persistent uncertainty and geopolitical tensions are undercutting world’s economic growth.11

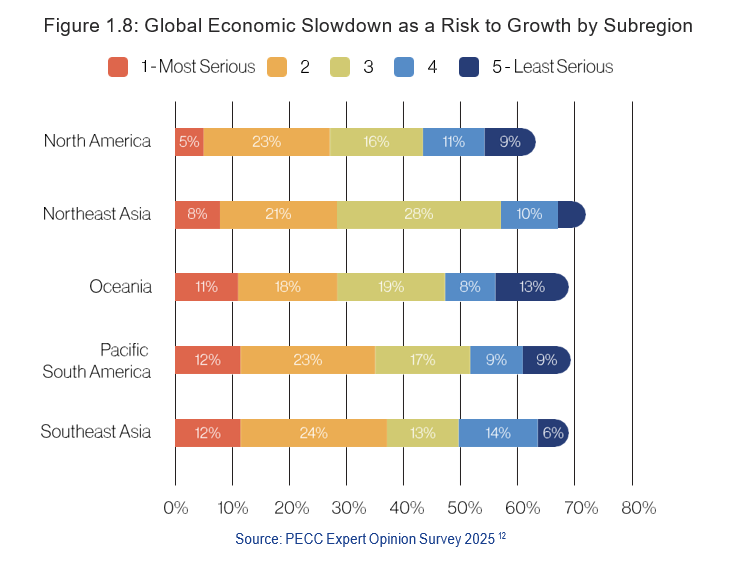

The global economic slowdown is transmitted to individual economies via a subdued investment climate, cautious consumer behavior, and pressures on employment, affecting both advanced and developing economies. In the PECC survey, more than 63% of respondents from all subregions identify the issue as a key risk to their economy’s growth (Figure 1.8).

9 World Bank Group (2025). “Global Economic Prospects”, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/global-economic-prospects

10 The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2025). “OECD Economic Outlook: Tackling Uncertainty, Reviving Growth”, June 2025, Volume 2025/1, No. 117.

11 IMF (2025), “Global growth expected to decelerate as trade-related distortions wane”, World Economic Outlook Update, July.

12 Percentages are shown if they are 5% or greater.

GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAIN DISRUPTION

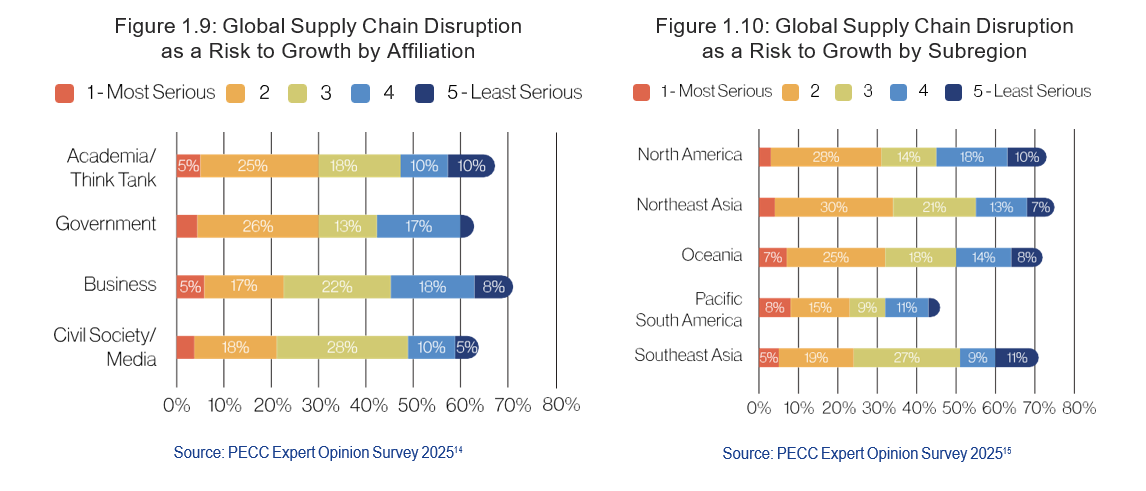

“Global supply chain disruption” is ranked as the No. 3 risk to growth (Figure 1.5). The concern may stem from multiple considerations such as situations in key flashpoints and natural disas- ters. Also, geopolitical tensions have prompted firms to pursue diversification. Companies are scrambling to move their production lines back home (i.e. onshoring) or closer to home (i.e. nearshoring) to mitigate risks.

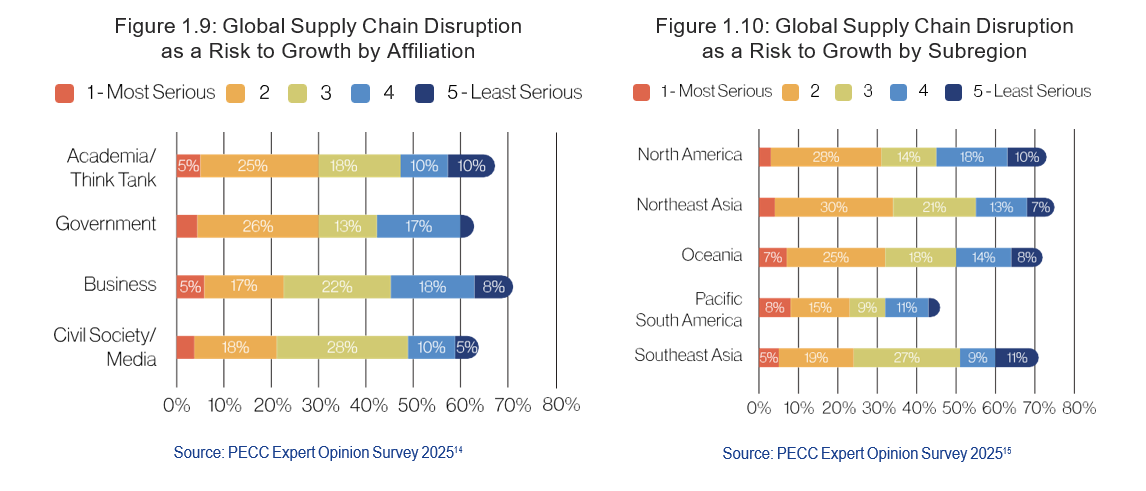

Business participants express more concern in the survey about supply chain disruption than their non-business counterparts, with more than 70% of the former picking it as their risk to growth (Figure 1.9). The former are facing mounting challenges to diversify. For example, unwinding from certain markets or suppliers can be infeasible and financially risky especially when done during a period of heightened market uncertainty.

Global supply chain disruption is a shared concern across all subregions, but some varia- tions exist (Figure 1.10). More than 70% of survey subjects from North America, Northeast Asia, Oceania, and Southeast Asia cite it as a risk to growth. However, less than half (46%) of participants from South Pacific America do so. This wide margin may be explained by the latter’s export composition. As primary exporters of commodities and agricultural products, they are less vulnerable to supply chain shocks. In contrast, manufacturing-heavy economies rely on intermediate goods. They have longer value chains with parts and com- ponents sourced from various locations, making them susceptible to the disruptive effects of tariffs on their operations.

14 Percentages are shown if they are 5% or greater.

15 Percentages are shown if they are 5% or greater.

INFLATION/ COST OF LIVING

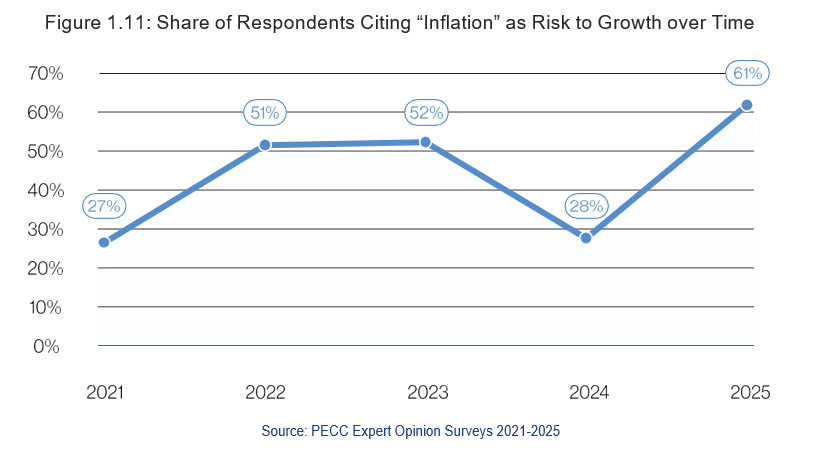

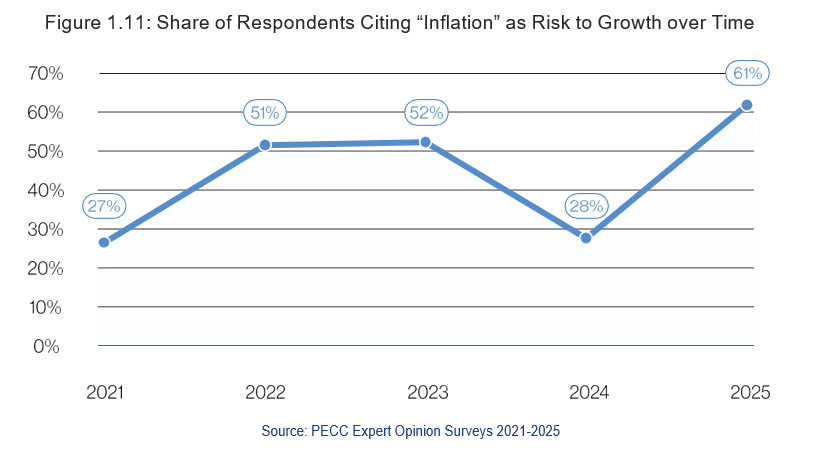

Survey respondents identify “inflation/cost of living” as the No.4 risk to growth (Figure 1.5). The result contrasts with the IMF’s estimation that global headline inflation will drop from 4.2% in 2025 to 3.6% in 2026.16 “Inflation” has been a choice for this question in the PECC survey over the years. The longitudinal comparison shows a higher percentage of participants this year choose inflation as a risk to growth, indicating a rising regional concern about the issue over the years (Figure 1.11).

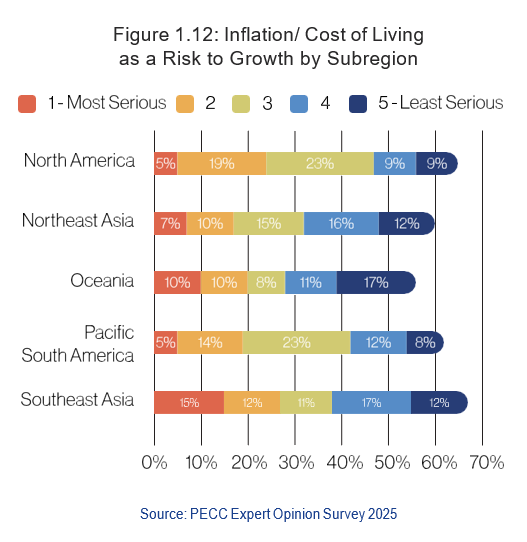

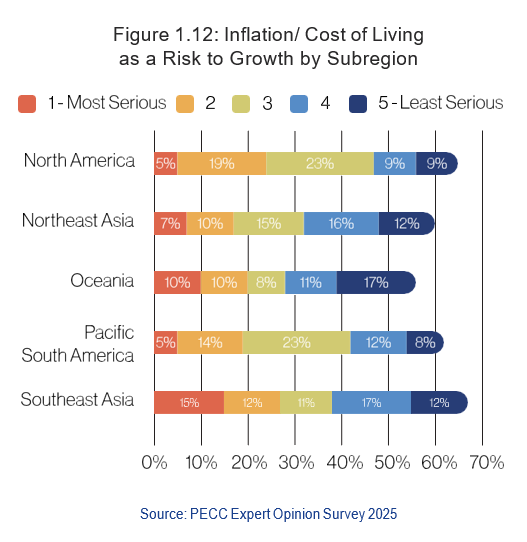

A close look at the PECC survey reveals that perspectives on inflation differ across subregions (Figure 1.12). Southeast Asian and North American individuals are most concerned, with 67% of the former and 65% of the latter pick it as their risk to growth.

A close look at the PECC survey reveals that perspectives on inflation differ across subregions (Figure 1.12). Southeast Asian and North American individuals are most concerned, with 67% of the former and 65% of the latter pick it as their risk to growth.

CLIMATE CHANGE/ NATURAL DISASTER

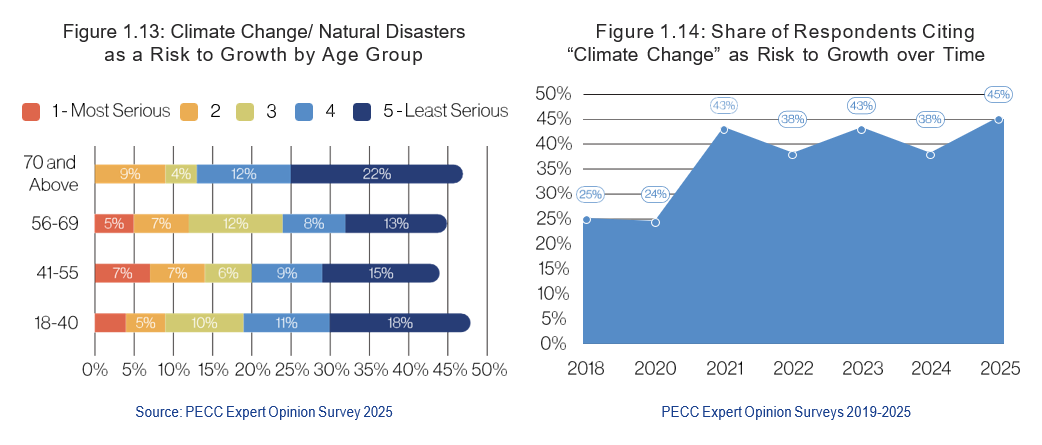

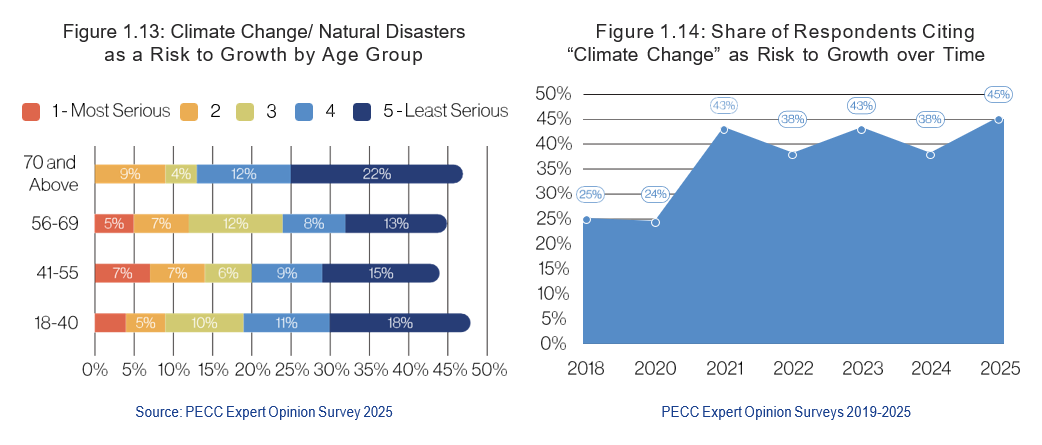

“Climate change/natural disasters” emerges as No.5 risk to growth (Figure 1.5). Contrary to conventional belief, older generations (especially those over 70) are as likely as younger ones to regard it as a serious problem (Figure 1.13).

“Climate Change” has been a choice for this question in the PECC survey over the years. The longitudinal trend shows increased percentage of participants selecting it as risk to growth (Figure 1.14). This indicates that the effect of climate change has been more widespread and hence felt by more individuals over time.

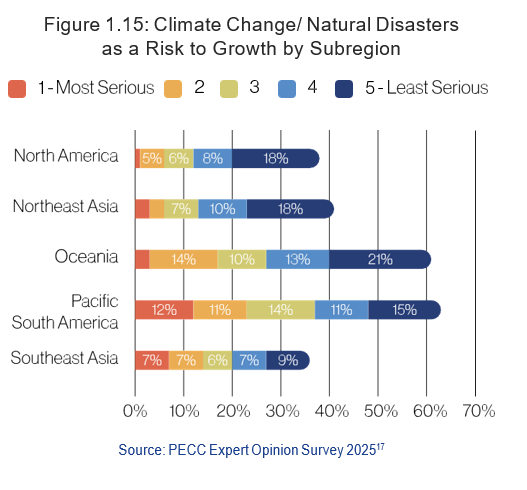

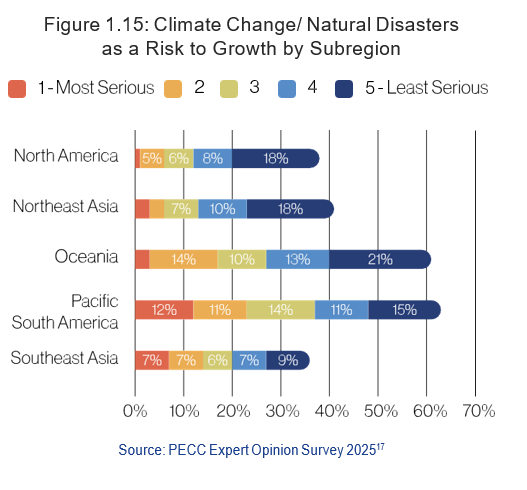

The PECC survey uncovers cross-subregional variations (Figure 1.15). Respondents living in Pacific South America and Oceania are the most worried. About 60% of these individuals cite the issue as their risk to growth, as compared to about 36-42% of their counterparts elsewhere. This result may be attributed to the two subregions’ unique geographical vulnerabilities. Illustratively, Oceania has several low-lying islands or communities. Rising sea levels cause coastal erosion and freshwater contamination, threatening their livelihood and existence.

The PECC survey uncovers cross-subregional variations (Figure 1.15). Respondents living in Pacific South America and Oceania are the most worried. About 60% of these individuals cite the issue as their risk to growth, as compared to about 36-42% of their counterparts elsewhere. This result may be attributed to the two subregions’ unique geographical vulnerabilities. Illustratively, Oceania has several low-lying islands or communities. Rising sea levels cause coastal erosion and freshwater contamination, threatening their livelihood and existence.

Regarding Pacific South America, rising temperatures accelerate the melting of tropical glaciers, jeopardizing the freshwater supply for the populations and water-reliant agricultural sector. Furthermore, the subregion is prone to the negative impacts of El Nino and La Nina phenomena, making them suffer from severe floods, landslides, and droughts.

APEC tackles climate change and natural disasters through bolstering sustainability and resilience. For example, the Bangkok Goals on Bio-Circular-Green (BCG) Economy encourages trade and investment in environmental goods and services, as well as circular economy practices. The San Francisco Principles on Integrating Inclusivity and Sustainability into Trade and Investment Policy strengthens regional cooperation to supports sustainable growth. Moreover, PECC has explored the relationship between trade and climate change through its Signature Project on FTAAP.

17 Percentages are shown if they are 5% or greater.

18 The PECC’s Policy Brief argues that the current trading system worsens and cites two main reasons, which are environmentally harmful subsidies and tariffs and non-tariff measure escalation in developed economies. For details, see Rory McLeod (2024). “Trade and Climate Change”, Policy Brief, PECC Signature Project: FTAAP Pathways to Prosperity, June.

The Era of Uncertainty

UNDERSTANDING UNCERTAINTY

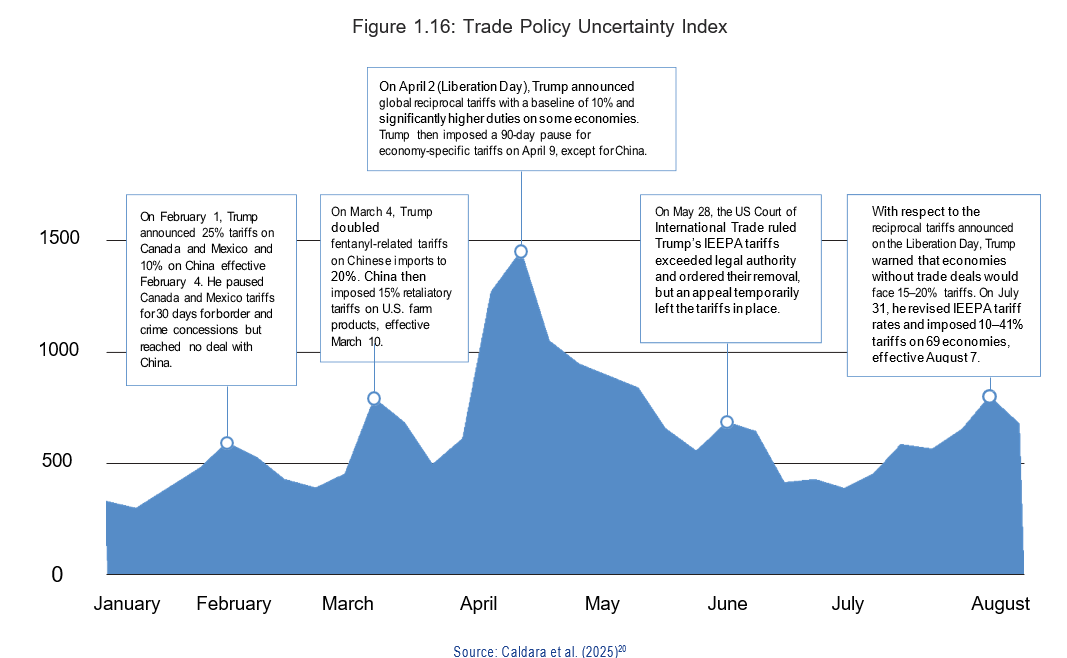

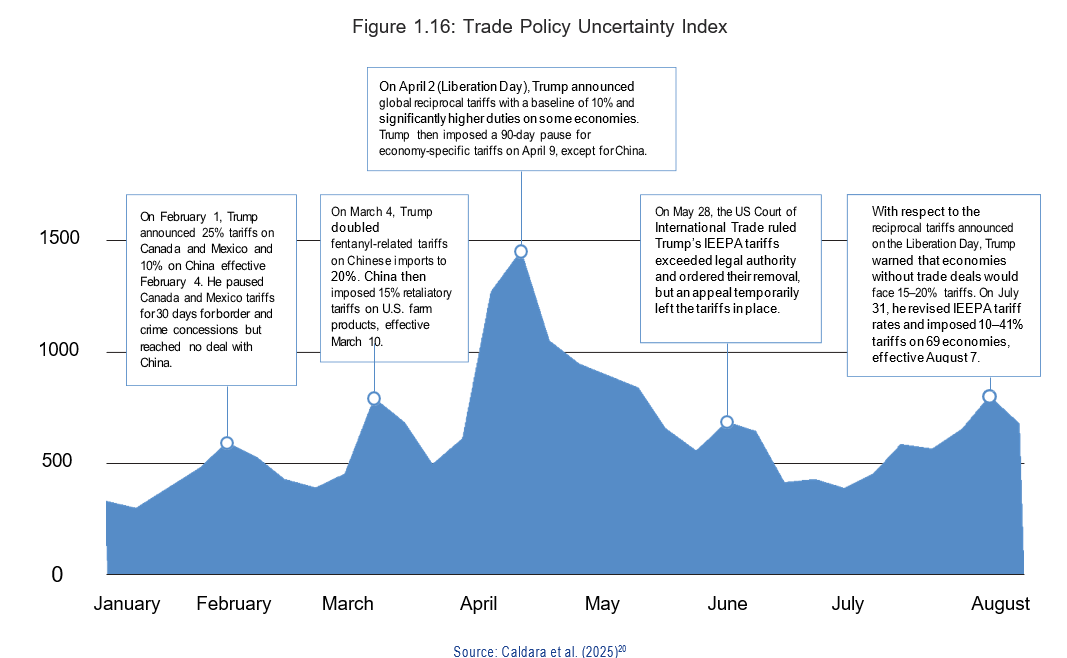

The current environment is characterized by high level of uncertainty. Rising protectionism and abrupt policy changes have injected unpredictability into the world economy. The Trade Policy Uncertainty Index reveals that trade policies became more unpredictable since January 2025 (Figure 1.16). According to the Yeouido Declaration adopted at the PECC Standing Committee meeting in August 2025, the Asia-Pacific is facing “the most consequential challenges to the rules-based open and liberal trading system in the 21st century, marked by rising economic uncertainty and a resurgence of protectionism.”19

19 Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC) (2025). The Yeouido Declaration, August 13. https://www.kiep.go.kr/boardDownload.es?bid=0053&list_no=22507&seq=1

20 The Index tracks the frequency of the discussion surrounding the policy unpredictability by major newspapers. For detail, see Caldara, Dario, Matteo Iacoviello, Patrick Molligo, Andrea Prestipino, and Andrea

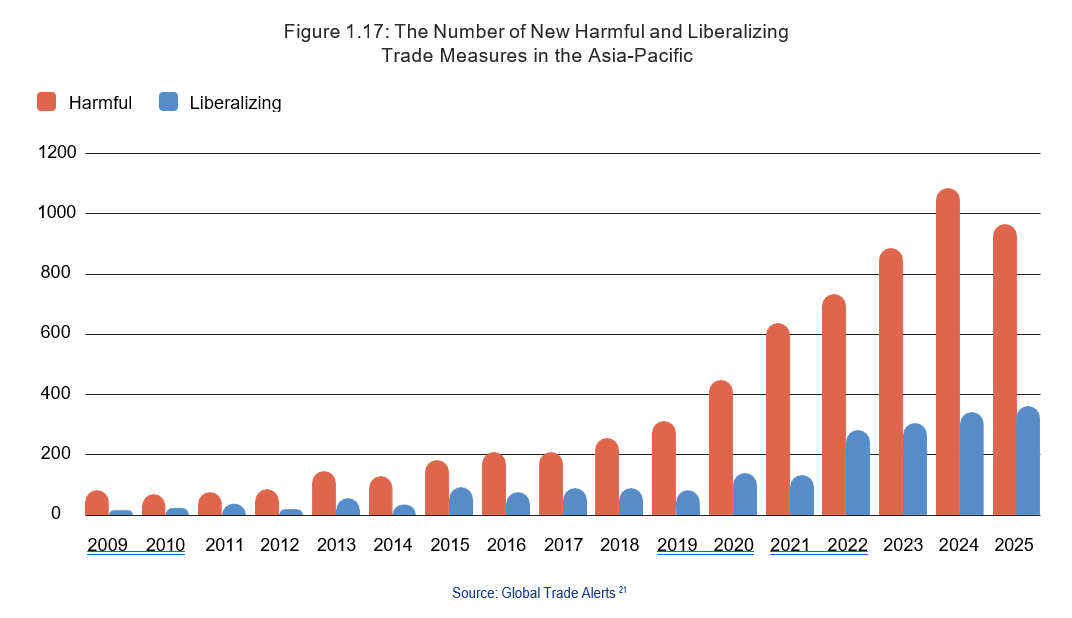

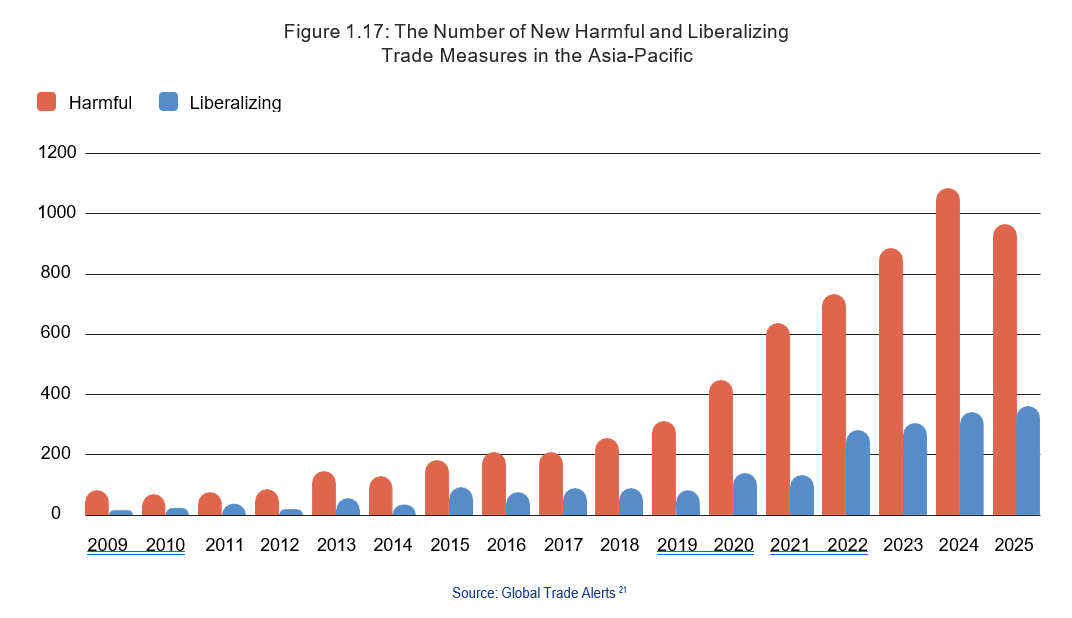

The Asia-Pacific has witnessed a consistent rise in new harmful trade measures since 2017, outnumbering new liberalizing ones and adding greater complexities for companies (Figure 1.17). This renders supply chains more prone to sudden interruptions. Consequently, firms are struggling with long-term planning due to the unpredictable nature of these new economic barriers.

To understand more about what has fueled this trend, the PECC survey probes the underlying causes behind the negative sentiments towards trade and globalization.

Raffo (2025), “Does Trade Policy Uncertainty Affect Global Economic Activity?” Data reporting cut-off date was 8 August 2025.

21 Global Trade Alert (2025). GTA Data Center. https://globaltradealert.org/data-center. Data reporting’s cut-off date was 12 August 2025.

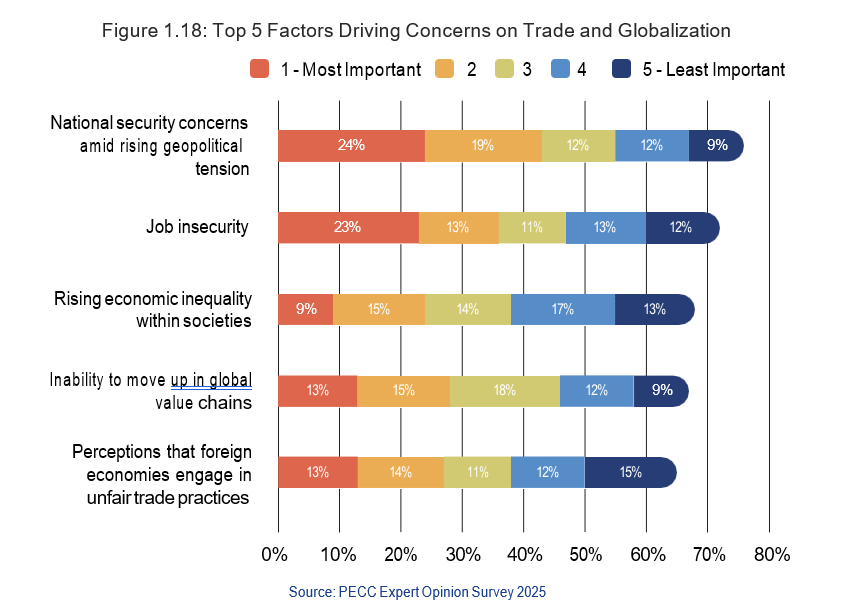

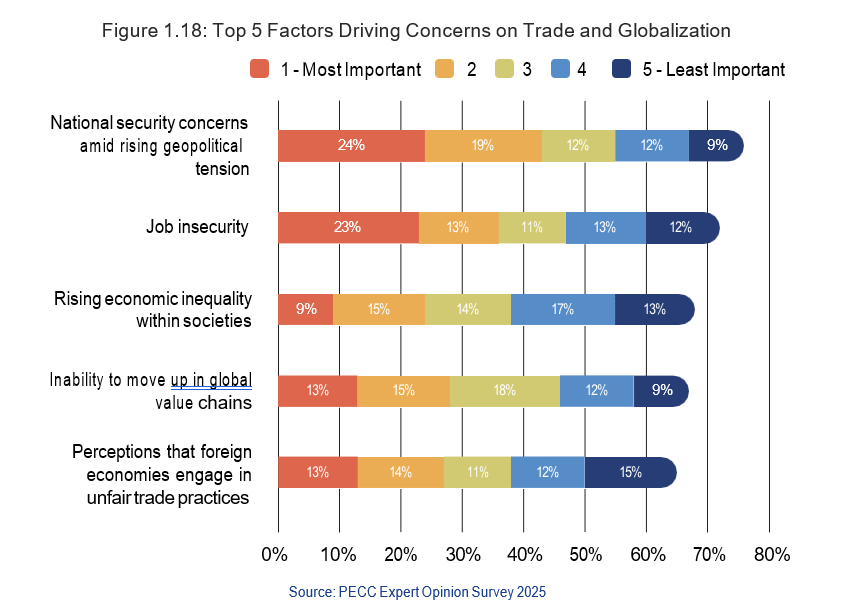

The most important reason for the opposition to trade and globalization is “national security concerns amid rising geopolitical tensions”, with 76% of survey subjects citing it (Figure 1.18). As geopolitical tensions intensify, economic issues are increasingly viewed through a securi- ty lens. Subsequently, policymakers prioritize security over market efficiency. The advanced technology sector illustrates this point. Governments are using export controls and restric- tions to achieve technological leadership and prowess and reduce dependency on their rivals and adversaries.

The second most important root cause of opposition to trade and globalization is the fear of unemployment. From the PECC survey, 72% of participants are concerned about “job insecurity” (Figure 1.18). One possible explanation may be that workers are concerned about losing the jobs they have, even if it is possible to obtain another job, albeit less attractive job, in otherwise robust economy. Workers may also fear that emerging technologies, such as artificial intel- ligence (AI), will cause their jobs to be replaced by machines. These advancements are re- shaping labor markets and may in the future contribute to recent layoffs. The World Economic Forum’s survey finds a significant skill-job mismatch, with 63% of the organizations identifying skills gaps in the labor market as the biggest factor hindering their transformation.22

22 WEF (2025). The Future of Jobs Report 2025.

“Rising economic inequality within societies” emerges as the third most important concern about trade and globalization, with 68% of survey subjects choosing it (Figure 1.18). The issue has worsened in the past three decades. During this period, income inequalities in more than half of all economies and close to 90% of advanced ones were widened.23 This phenomenon may be explained by various elements ranging from new technological innovations, unequal access to finance, to stringent labor markets.

“Rising economic inequality within societies” emerges as the third most important concern about trade and globalization, with 68% of survey subjects choosing it (Figure 1.18). The issue has worsened in the past three decades. During this period, income inequalities in more than half of all economies and close to 90% of advanced ones were widened.23 This phenomenon may be explained by various elements ranging from new technological innovations, unequal access to finance, to stringent labor markets.

Another reason fueling worries about trade and globalization is a decline in international competitiveness. The PECC survey show that 67% of respondents select “Inability to move up in global value chains” as the fourth most important factor (Figure 1.18). The finding may reflect the struggles faced by many economies in advancing their positions within global value chains. Climbing the value chains is vital for economic growth and development. Historically, an economy’s success hinged on its ability to produce and export the entire goods. However, today’s success is increasingly determined by its ability to perform specific tasks within complex cross-border value chains.

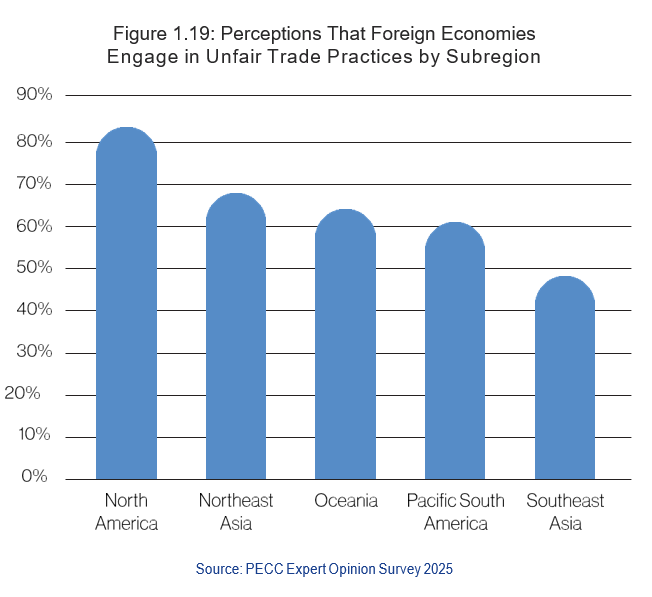

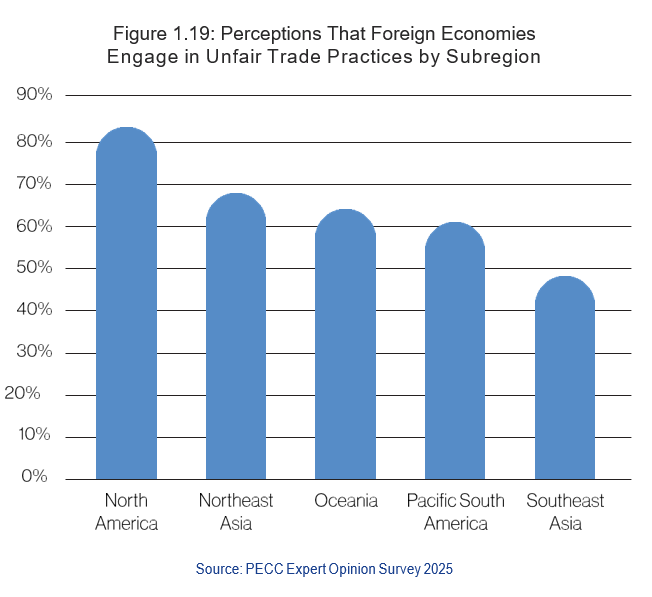

Concerns about trade and globalization also stem from “perceptions that foreign economies engage in unfair trade practices” which is ranked as the fifth most important factor by 65% of survey subjects (Figure 1.18). This view is most pronounced in North America as compared the other subregions (Figure 1.19).

23 IMF (2025). “Income Inequality”, https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/Inequality/introduction-to-inequality

The Era of Uncertainty

IMPACT OF UNCERTAINTY

Impact on Economic Outlooks

Uncertainty is clouding the economic outlook. The remaining part of 2025 will be driven by multiple headwinds. The effects of front-loading trade in advance of tariffs and other risk- mitigating strategies are set to fade, and the future interactions between economies are becoming increasingly unpredictable. For one thing, protectionism can trigger a new cycle of retaliation and formation of new trade and investment groupings, ultimately causing greater market fragmentation.

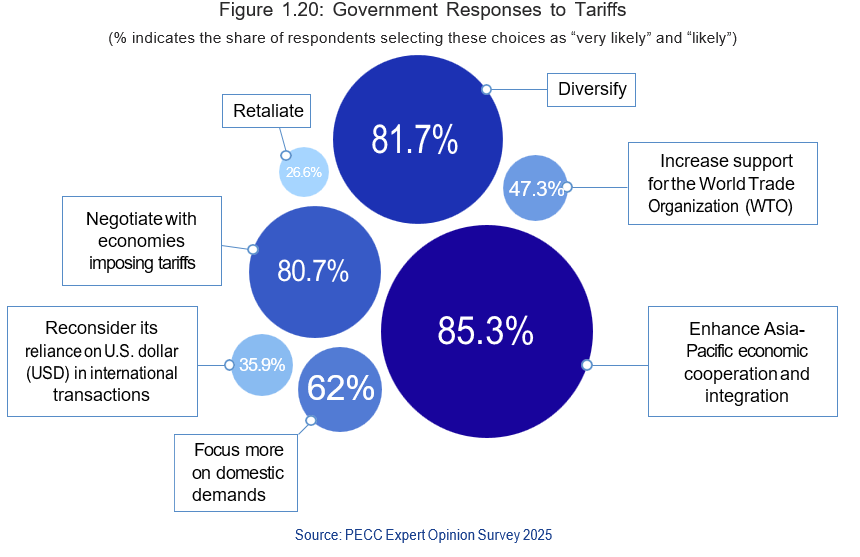

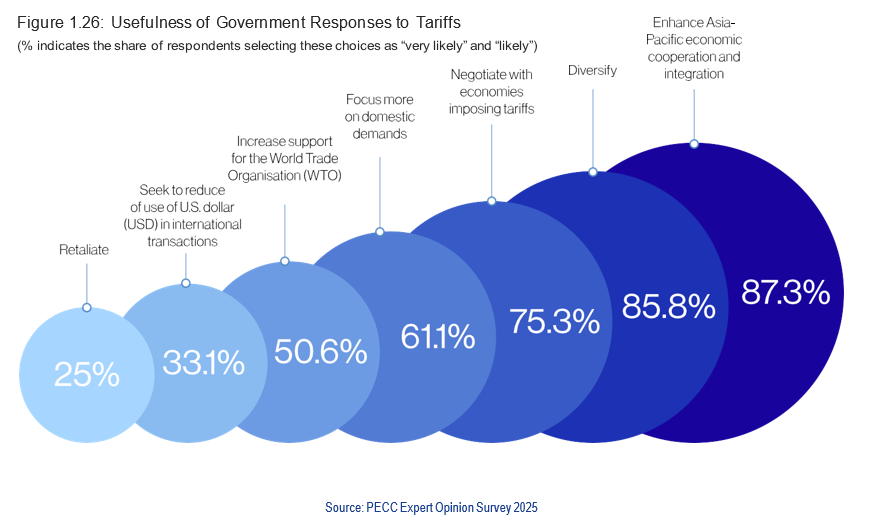

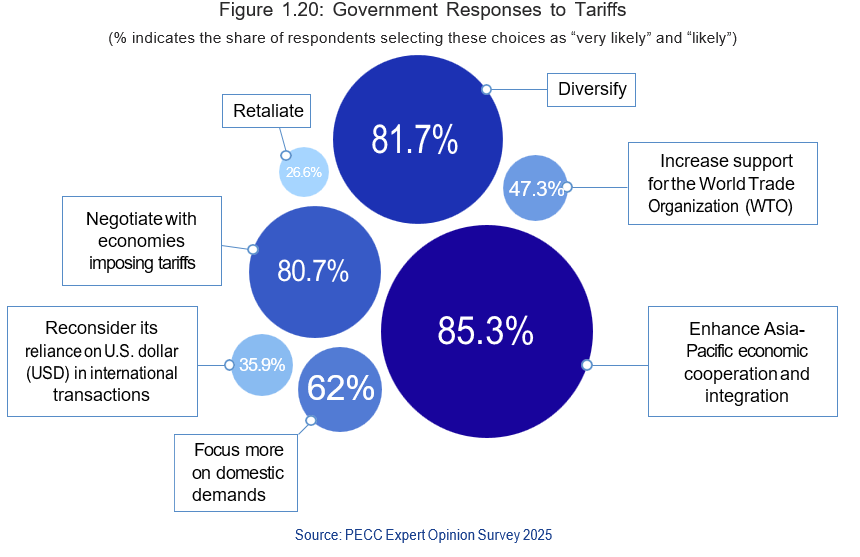

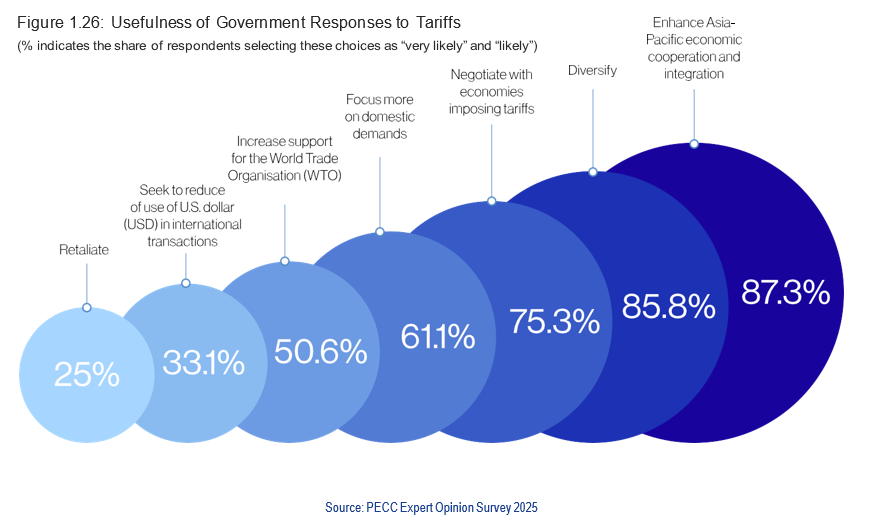

The imposition of tariffs by some economies may prompt other economies to respond in one way or another. As the PECC survey demonstrates, responses to tariffs on their exports vary (Figure 1.20). The most common policies are regional collaboration and integration, negotiation, and diversification. Over 85% of survey subjects believe their governments would “enhance Asia-Pacific economic cooperation and integration”. Furthermore, about 80% of them anticipate their authorities would “negotiate with economies imposing tariffs” or “diversify”. Despite being a less common response, “retaliate” is seen as a policy alternative. More than a quarter (27%) of participants suppose it to be their governments’ responses.

These findings concur with recent developments. Different economies have employed different approaches. Many governments have chosen negotiation to resolve their trade tensions. Other policies include more reliance on domestic demand, diversification, and regional economic cooperation and integration. In addition, some economies have retaliated. For example, China increased trade barriers on the US products. Also, Canada retaliated with 25% duties on several American goods ranging from agricultural products to cars in March 2025, but removed them in September 2025 following the US decision to grant a duty-free to most Canadian products under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

A variety of responses not only adds complexity to the world economy but also lessens one’s ability to predict the future, making it even more uncertain for businesses to navigate. This element may shape survey subjects’ views on the economic outlooks. As mentioned above, the PECC survey reveals that the majority (60%) of respondents anticipate the world economy to be weaker or much weaker in the next few years (Figure 1.2).

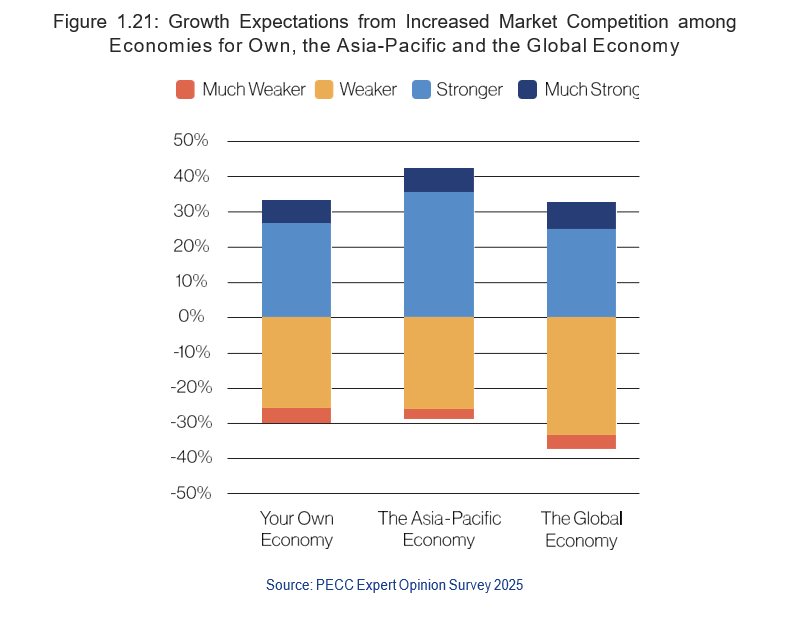

The increase in market competition among economies is also dimming to their outlooks. When economies become entangled in a zero-sum game, the potential for mutually beneficial cooperation diminishes. Supply chain fragmentations and the reduction in foreign direct investment result, impeding growth. Referring to the PECC survey, due to the competition, around 30%, 27%, and 36% of participants respectively expect the decreased GDP for their own economy, the Asia-Pacific, and the global economy within the next few years (Figure 1.21). This outlook is shared by WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala. She contends that the WTO’s analysis reveals the US-China trade escalation could lead to a reduction of as much as 80% of their bilateral goods trade and risk breaking the global economy into two separate blocs. If the latter happens, the WTO estimates that world’s real GDP to be lower than it would be otherwise by nearly 7% by 2040 as a result.24

24 World Trade Organization (WTO) (2025). Statement by the Director-General on escalating trade tensions, April 9. https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/news25_e/dgno_09apr25_e.htm; and WTO (2025). Global Trade Outlook and Statistics, April.

Impact on Cross-Border Trade and Supply Chains

Protectionist measures diminish cross-border trade. For example, duties make imports more expensive, discouraging demand for them. Tariffs also tempt exporting economies to turn inward and focus more on propping up their internal markets instead of accessing external ones. The PECC survey shows that 62% of participants expect their policymakers to focus more on domestic demand if tariffs are applied to their exports (Figure 1.20). A similar percentage of respondents regard this strategy as a useful response (Figure 1.26).

As mentioned above, different responses to protectionism and the subsequent interactions among economies amplify market uncertainty, further suppressing global trade. The IMF’s analysis unveils a strong relationship between the uncertainty in the global economy and international trade. When uncertainty rose by one standard deviation, bilateral trade was found to drop by 4.5%.25 This resonates with the PECC survey finding that 54% and 35.3% of survey subjects anticipate their exports and imports respectively will decline in the next 2-3 years in the protectionist scenario (see survey question 4 in Annex A for details).

High tariffs can negatively affect employment in export-led economies. Exporters may find their products are less price-competitive. If they are unable to secure alternative markets, they may need to reduce their production and workforce to stay afloat. This can soften labor markets and worsen unemployment. The PECC survey supports this logic, with about 61% of participants anticipating that tariffs will increase unemployment in their economies (see survey question 4 in Annex A for details).

Fueled by geopolitical tensions and national security concerns, protectionism is reconfiguring global supply chains. This trend is already prominent in some sectors where governments are implementing new industrial policies to gain a competitive edge and bring certain production lines vital to their national interests back home (i.e. “reshoring”). For instance, US policies are geared towards galvanizing homegrown capacities in semiconductors and AI. Trade patterns and mining investments in critical mineral sector are increasingly influenced by security calculations. Launched in 2022, the Mineral Security Partnership is aimed at strengthening critical mineral supply chains among trusted partners.

Formal agreements can alter trade and supply chain patterns. Illustratively, the recent US- Vietnam deal charges a 20% duty on most of the latter’s exports to the former. However, the higher 40% levy is applied on “transshipped” good passing through Vietnam to the US market. The deal could lead to trade pattern shifts and supply chain fragmentations between these two economies and beyond. In addition to binding deals, enterprises are changing supply chains to de-risk from the US and China. Because their bilateral talks to resolve their trade conflict have yet finalized, companies are scrambling for “backup” suppliers and markets to mitigate overexposure to the risks associated with any single economy. The PECC survey confirms this trend. About 80% of survey subjects expect their governments to very likely or likely diversify (Figure 1.20), and 86% of them consider it as a useful response (Figure 1.26).

Impact on Cross-Border Investment

Protectionism affects cross-border investment. Import duties can disrupt supply chains and press firms to relocate, altering their decisions on where they will place their investments. Also, protectionism can manifest in various forms of investment restrictions such as rigorous investment screening, suppressing cross-border investment. This logic is echoed by the PECC survey. About 41% and 30% of respondents expect that their economy will suffer from decreased inward and outward investments respectively in the next few years due to rising protectionism (see survey question 4 in Annex A for details).

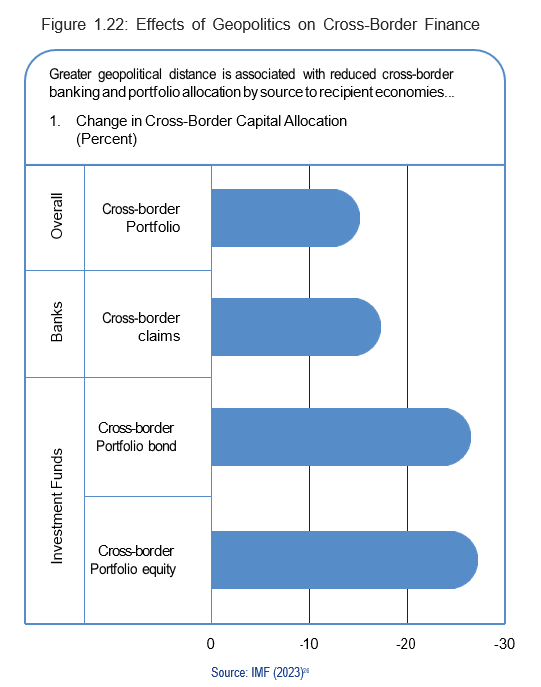

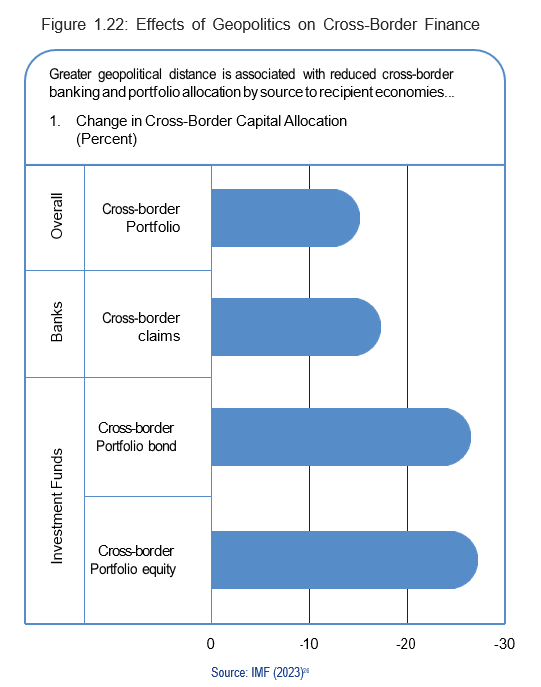

Rising geopolitical tensions are causing econmies to tighten restrictions on foreign investment, particularly in key sectors with national security implications. This climate of uncertainty leads entrepreneurs to pause or postpone new investments. Additionally, the risk of conflicts in global flashpoints is increasing insurance premiums and costs for investors, further discouraging them from investing. According to the IMF (2023), a one-standard- deviation increase in geopolitical tensions between investing and recipient economies dwindles the reduction of cross-border portfolio and bank allocation by about 15%, and cross- border portfolio bonds and equities by about 25% between the individual economies (Figure 1.22).

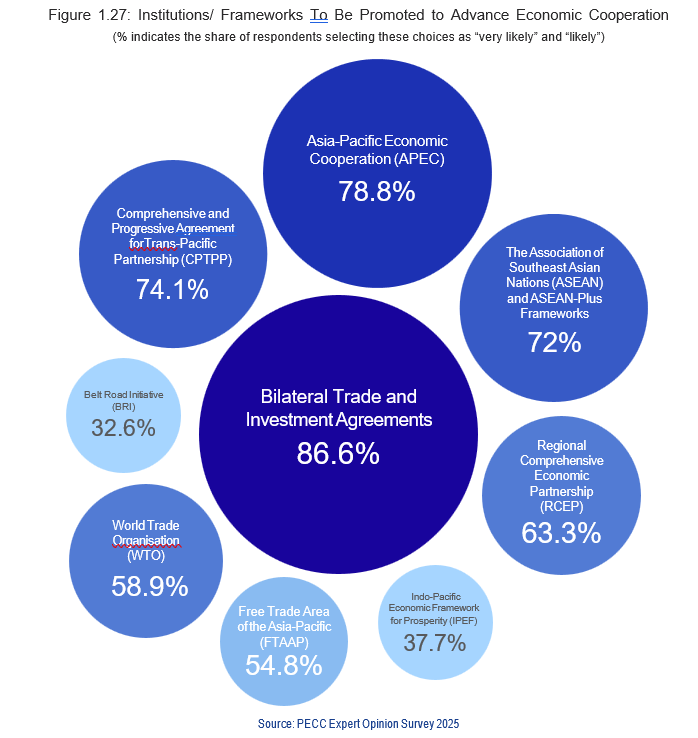

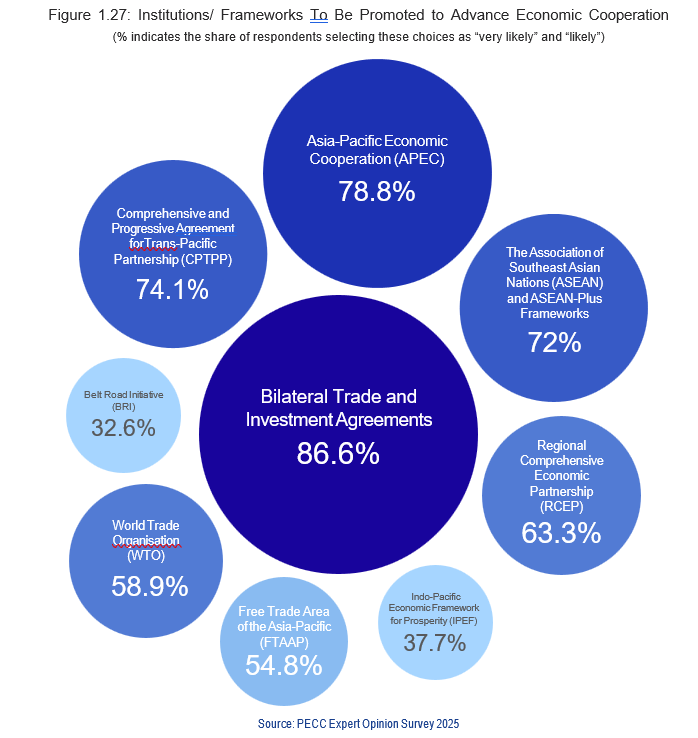

As the PECC survey reveals, about 87% of participant anticipate that their governments would “very likely” or “likely” resort to bilateral trade and investment arrangements (Figure 1.27). This suggests that the world may witness the burgeoning of new bilateral investment treaties to promote mutual investments, exacerbating cross-border investment fragmentation.

26 IMF (2023). “Chapter 3: Geopolitics and Financial Fragmentation: Implications for Macro-Financial Stability” in Global Financial Stability Report: Safeguarding Financial Stability amid High Inflation and Geopolitical Risks (pp. 81-101), April.

Impact on Financial Markets

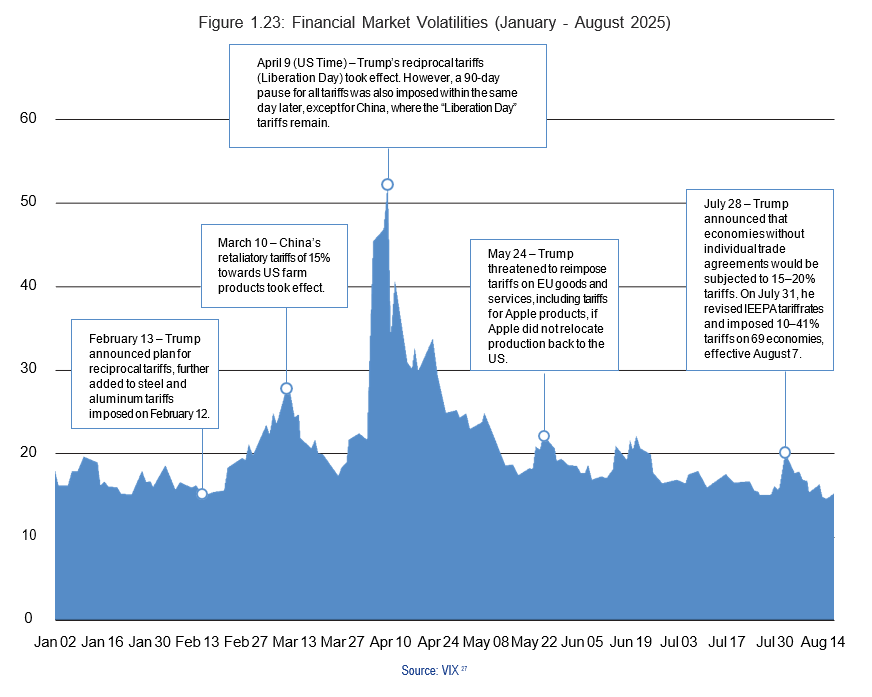

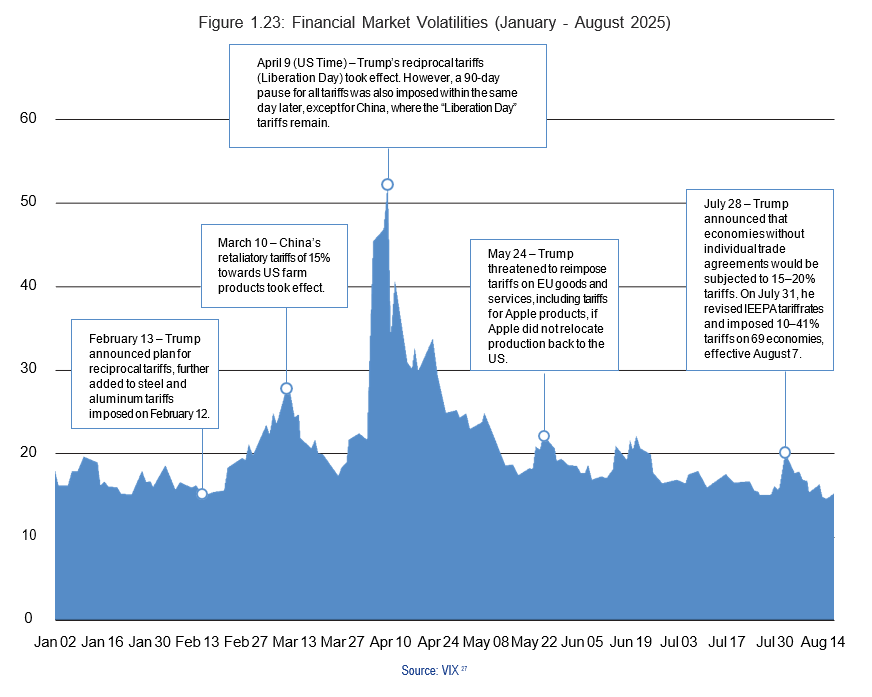

The era of uncertainty is bringing disruptions to the financial markets. While the compounding effect of factors ranging from geopolitical conflicts to shifts in investment regimes by major economies can cause market volatilities, one should not dismiss a direct link between trade policies and financial market turmoil. In early April, Trump unveiled the “Liberation Day” tariff imposing the 10-41% universal levy on all imports (except Canada and Mexico) and higher sector-specific duties. China immediately and equivalently retaliated with its 34% tariffs on the American goods. These incidents sent shockwaves through financial markets, making it plunge by 10.5% in the S&P 500 Index. This explains the biggest uptick in the VIX Index occurred in that month (Figure 1.23). Although the US-China truce brought some calm, there were other less dramatic new episodes of market nervousness.

Moreover, geopolitical dynamics are affecting cross-border financial flows. Pressured by a desire to prevent competitors or adversaries from accessing the sectors with national security implications, several governments alter rules governing inward and outward investments. Abrupt policy shifts will further complicate the investment climate and worsen financial market volatilities.

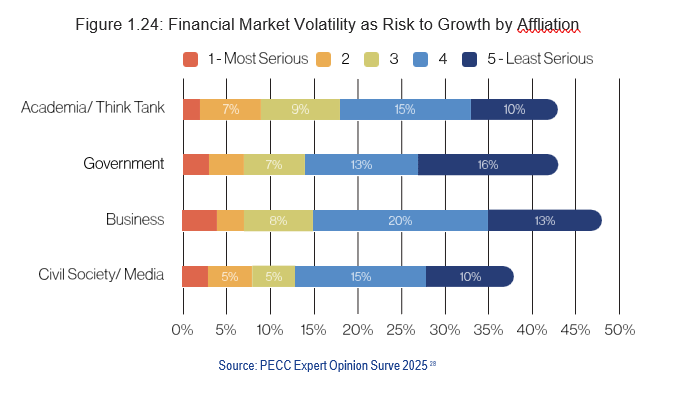

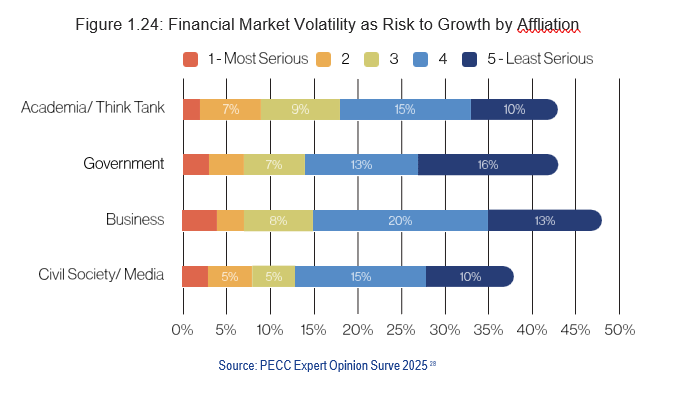

The PECC survey reveals that risk perceptions of financial market volatility differ across affiliates (Figure 1.24). While government, academic/thinktank, and civil society/media participants recognize this issue as risk to growth, a higher proportion (48%) of the private sector participants feel it. Being on the front lines, companies directly experience how financial market turmoil hinders their access to capital, investment plans, and day-to-day operations. Also, sudden market swings can significantly alter the valuation of a company’s assets, complicating their merger and acquisition plans. Consequently, enterprises tend to adopt a “wait-and-see” approach by delaying or cancelling investments.

The PECC survey shows that more than one-third (36%) of survey subjects believe their policymakers will “very likely” or “likely” to “reconsider its reliance on the U.S. dollar (USD) in international transactions” as a response to rising protectionism (Figure 1.20). Despite some efforts to de-emphasize the importance of the dollar, the greenback dominates the global reserves holdings, export invoicing, and cross-border transactions (Figure 1.25).

It is worth noting that financial markets have shown resilience as seen by the fact that recent instabilities were short-lived. The stock markets in the US, the European Union, and Japan quickly bounced back from the “April shock” following the announcement of the US Reciprocal Tariffs, and have remained steady since. This resilience may reflect a cautious reassessment by investors who have postponed large-scale sell-offs. Nevertheless, risks should not be underestimated. In the current climate of uncertainty, even a single event could rattle confidence and send markets tumbling again.

Importance of APEC & Priorities for APEC Leaders

IMPORTANCE OF APEC

There are no easy solutions to the problems generating by this era of uncertainty. Protectionism threatens the international rules-based trading system by undermining the non-discrimination principle enshrined by the WTO. Rapid shifts in economic or economic- related policies are adversely impacting market sentiment. Deepening geopolitics and market competition continue to cloud growth prospects. These developments work against collective efforts to foster a more stable and resilient global and regional economy. Against this backdrop, the PECC survey surfaces respondents’ views on how to propel economic cooperation in this challenging time. Many participants consider regional collaboration as a buffer against protectionism. The overwhelming majority (85%) of them believe that their governments will “very likely” or “likely” to augment “Asia-Pacific economic cooperation and integration” as part of their responses to tariffs on their exports (Figure 1.20). 87% of them also consider this action a useful response in this situation (Figure 1.26).

In terms of specific institutions or frameworks to be simultaneously promoted to advance economic collaboration, the PECC survey suggests the need for bilateral trade and investment agreements, with 87% of respondents expecting their governments will resort to them (Figure 1.27). With respect to regional forums, APEC is seen as the most relevant regional framework, with about 79% of respondents believing their policymakers will lean on it. Despite its non- binding characteristic, APEC’s values lie in its ability to convene multi-stakeholder dialogues allowing different players to exchange views on pressing regional economic matters and experiment with joint solutions to tackle them. As a result, APEC is dubbed as “an incubator of ideas” and has played a significant role in advancing discussions regarding regional economic cooperation.

The PECC survey reveals the usefulness of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), ASEAN and ASEAN-Plus frameworks, and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Overall, 74%, 72%, and 63% of respondents think their authorities will leverage CPTPP, ASEAN and ASEAN-Plus frameworks, and RCEP (Figure 1.27). These results align with developments in recent years. For instance, Indonesia formally applied for CPTPP membership in September 2024. Furthermore, RCEP parties are increasingly pursuing the implementation of the arrangement to cushion their economies against the effects of rising protectionism. In addition, the ASEAN Leaders’ Statement on Responding to Global Economic and Trade Uncertainties issued in May 2025 unveils the Organization’s plans to boost intra-ASEAN trade and investment.

It should be emphasized that participants’ preference for regional frameworks is not an indication that the WTO is irrelevant. 47% of survey subjects anticipate their authorities will “very likely” or “likely” increase support for the Organization amidst substantive tariffs on their exports (Figure 1.20). 50% of them consider it a suitable government response (Figure 1.26). Moreover, 59% of respondents think their policymakers would leverage the WTO to advance economic collaboration (Figure 1.27). Regional forums are set up to support the WTO. For example, APEC’s principle of “open regionalism” is deemed to complement the WTO system. By providing a platform for voluntary commitments and technical cooperation, APEC enhances its members’ capacity and political will to implement and adhere to the WTO rules. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted as a reflection of APEC’s success in its supportive role, rather than a sign of the WTO’s declining usefulness.

PRIORITIES FOR APEC LEADERS

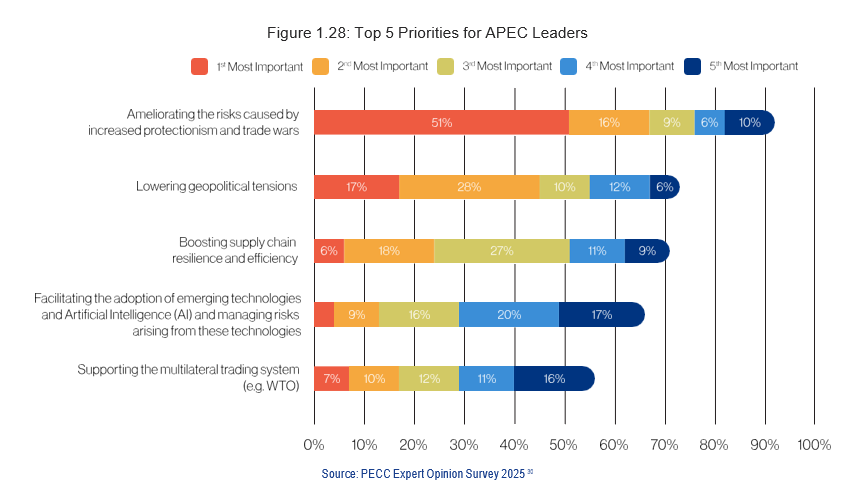

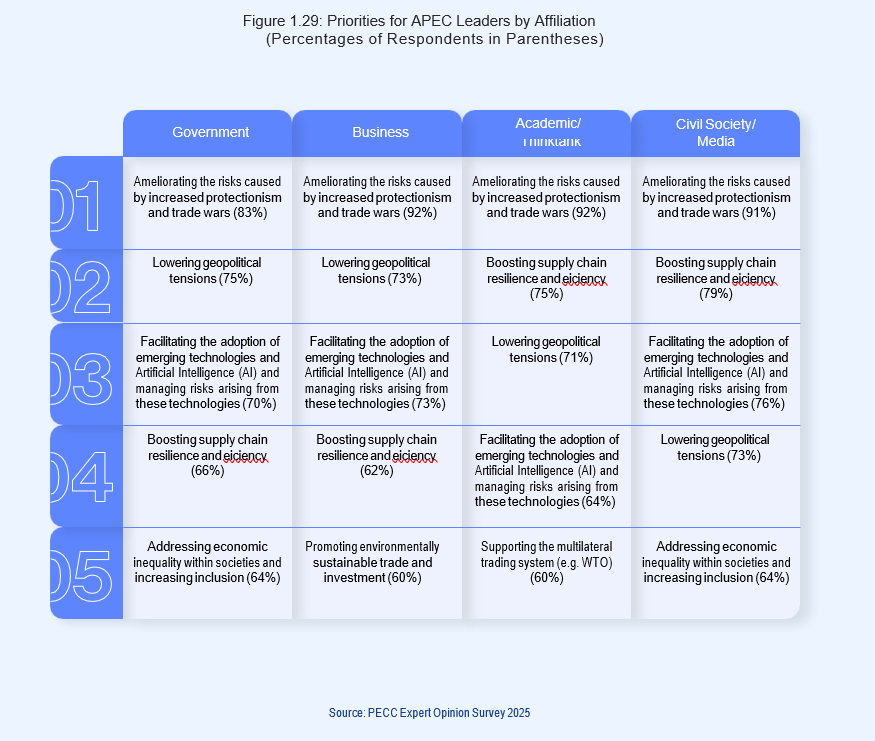

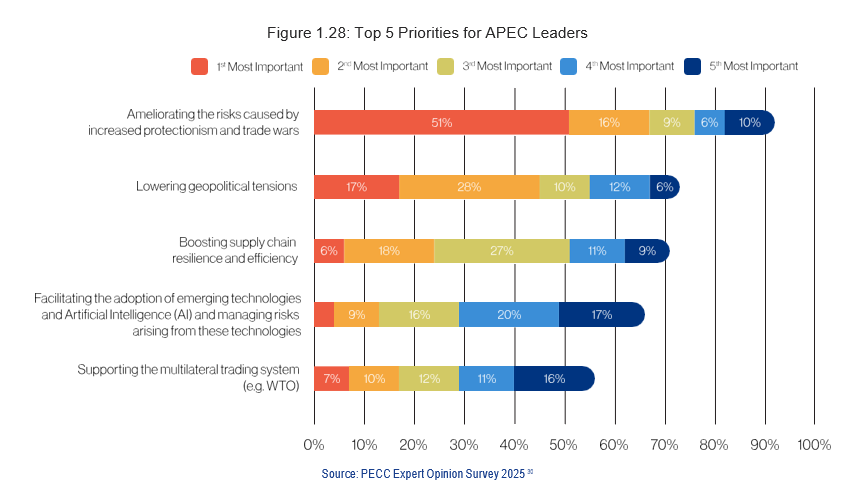

To tease out participants’ specific demands for APEC Leaders to push forward cooperation on certain issues, the PECC survey asked them to rank the priorities that APEC Leaders should address at their meeting (Figure 1.28). The top 5 priorities are:

- Ameliorating the risks caused by increased protectionism and trade wars;

- Lowering geopolitical tensions;

- Boosting supply chain resilience and efficiency;

- Facilitating the adoption of emerging technologies and AI and managing risks arising from these technologies; and

- Supporting the multilateral trading system (e.g. WTO).

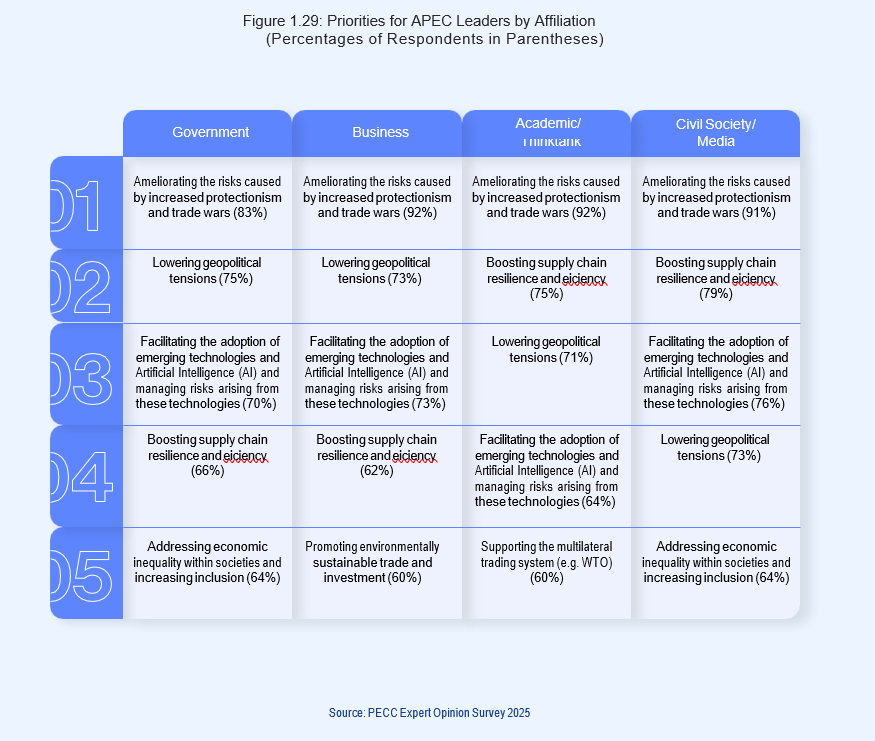

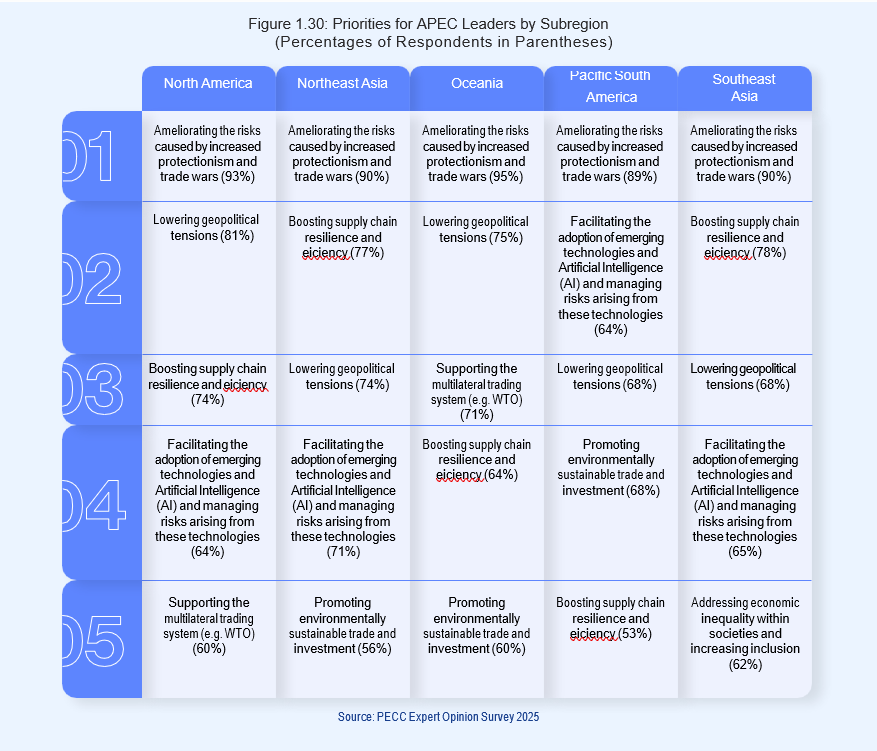

Priority No. 1: Ameliorating the Risks Caused by Increased Protectionism and Trade Wars

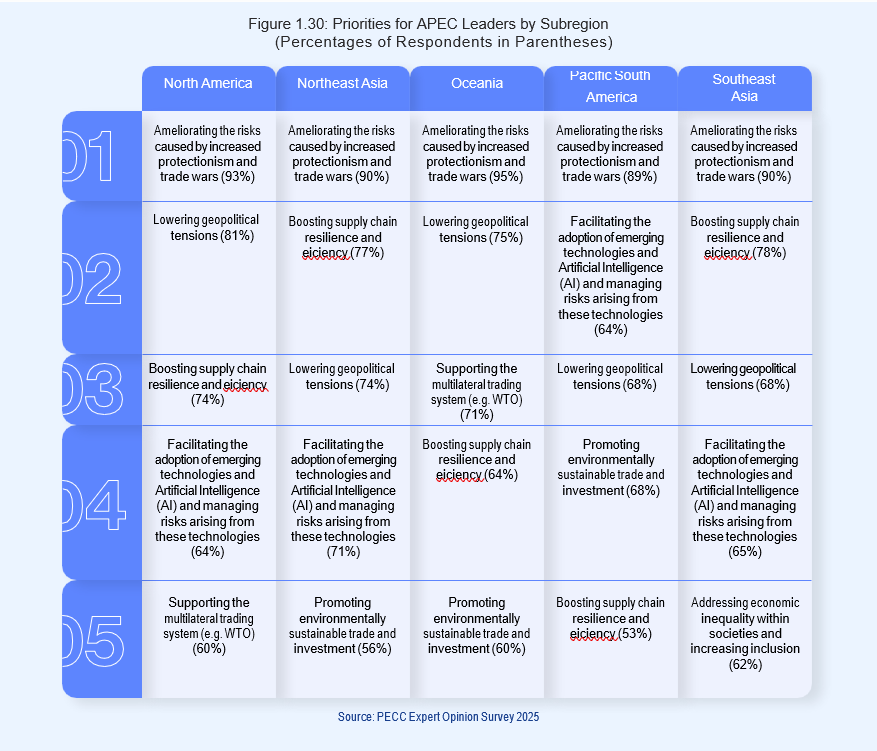

More than 90% of respondents pick “Ameliorating the risks caused by increased protectionism and trade wars” as the No.1 most important priority for APEC Leaders (Figure 1.28). All affiliations and subregions shared a similar perspective. In other words, this first priority is selected by more than 80% of participants from the government sector, as well as more than 90% of business, academic/thinktank, and civil society/media participants (Figure 1.29). About 90% of respondents from all subregions concur that this issue needs to be addressed immediately (Figure 1.30). These views resonate with the severity of a risk to growth earlier revealed by the PECC survey. 88% of respondents cite “increased protectionism and trade wars” as No. 1 most serious risk to growth (Figure 1.5).

APEC possesses unique characteristics which can be leveraged to alleviate rising protectionism and trade wars. For one thing, its role as a convenor of diverse economies in the Asia-Pacific is notable. The platform brings together members to exchange perspectives on pressing global and economic challenges or reveal justifications underlining their actions in a non-binding way. Also, APEC’s initiatives have advanced discussions on regional collaboration in several areas such as goods and services trade, regulatory coherence, trade facilitation and customs procedures as well as on policy approaches to micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs), digital economy, and sustainability. Furthermore, APEC enhances policy transparency through the Individual Action Plans which are regularly submitted by the member economies. The documents detail specific policy measures taken to accomplish the goals for free and open trade and investment. The information revealed can be used as a basis for talks to reduce protectionist impulses or a full-blown trade war.

Priority No. 2: Lowering Geopolitical Tensions

“Lowering geopolitical tensions” emerges as the No. 2 priority for APEC Leaders by the PECC survey participants, with 73% of them choosing it (Figure 1.28). Affiliation breakdowns show convergence on this view. More than 70% of survey subjects from all affiliations (i.e. government, business, academic/thinktank, and civil society/media) identify this issue as APEC Leader’s priority (Figure 1.29).

APEC can be used as a forum for diplomacy and negotiation to lessen geopolitical tensions. Each year, APEC hosts a meeting of foreign leaders and a meeting of Heads of State. Beyond the formal APEC meetings, bilateral talks on the sidelines of the official gatherings are also valuable. They not only unlock opportunities to reap mutual benefits from their bilateral collaboration but also resolve tensions, including geopolitical ones. Moreover, holding these bilateral talks concurrently with APEC meetings allows for issue linkage. In short, economies can trade concessions or gains across different platforms, using a less-important issue from one negotiation to secure a more-important one in another. This strategic flexibility enhances the likelihood of reaching more favorable outcomes than would have been possible in a single, isolated deal.

Priority No. 3: Boosting Supply Chain Resilience and Efficiency

“Boosting supply chain resilience and efficiency” is ranked as the No. 3 priority for APEC Leaders, with 72% of survey subjects choosing it (Figure 1.28). This matter is considered particularly important by individuals from North America, Northeast Asia, and Southeast Asia, where over 73% of them select it (Figure 1.30).

This prioritization appears to be driven more by respondents’ risk perception. The Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (GSCPI) has shown little pressure since the beginning of 2025.31 Nevertheless, “Supply chain disruptions” comes in as the No. 3 risk to growth (Figure 1.5) and this sentiment is shared across different subregions (Figure 1.10). In a climate of uncertainty, people may be less optimistic about the future of supply chains, resulting in their call for greater resilience to be a top priority for APEC Leaders.

31 Federal Reserve Bank of New York. “Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (GSCPI)”, https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/policy/gscpi#/interactive

Priority No. 4: Facilitating the Adoption of Emerging Technologies and AI and Managing Risks Arising from these Technologies

“Facilitating the adoption of emerging technologies and Artificial Intelligence (AI) and managing risks arising from these technologies” comes in as the No. 4 priority for APEC Leaders. 66% of participants choose it (Figure 1.28). The issue is equally important for business, government, and civil society players, with more than 72% of each of the groups citing it as a priority, as compared to 64% of their academic/thinktanks counterparts (Figure 1.29). This focus on technology shows up among Top 5 priorities in all subregions except Oceania (Figure 1.30).

The APEC Roadmap on Internet and Digital Economy (AIDER) promotes innovation, investment in digital infrastructure, and research. Also, PECC’s project on AI has advanced multi-stakeholder discussions on several topics, including AI ethics and responsible AI, SMEs’ AI adoption, inclusive sectoral transformation, socio-economic impact of AI, skill training and capacity building, and cooperation in AI governance.32

32 PECC Statement to the APEC Digital and Artificial Intelligence Ministerial Meeting August 4-6, 2025, Incheon, Republic of Korea, https://www.pecc.org/resources/statements/2799-pecc-statement-for-apec-dmm-2025/file

Priority No. 5: Supporting the Multilateral Trading System (e.g. WTO)

57% of respondents select “Supporting the multilateral trading system (e.g. WTO)”, making it the No. 5 priority for APEC Leaders (Figure 1.28). But a deeper look at the survey data reveal that the academic/thinktank respondents are the only group placing it among the Top 5 priorities (Figure 1.29). Regarding cross-subregional variations, only individuals from North America and Oceania include “Supporting the multilateral trading system (e.g. WTO)” in the Top 5 priorities (Figure 1.30).

In response to its critics, the WTO has made some recent headway. At the 13th Ministerial Conference (MC13), the members agreed to add new members and extend the moratorium on customs duties on electronic transmissions. They were also committed to restoring the full dispute settlement mechanism and enhancing the multilateral trading system. These outcomes demonstrate the Organization’s continued relevance.

APEC is supporting the WTO in various ways. In their 2025 Joint Statement, the APEC Ministers Responsible for Trade recognized “the importance of the WTO to advance trade issues and acknowledge the agreed upon rules in the WTO as an integral part of the global trading system.” The APEC members also pledged to “work collaboratively through APEC’s role as an incubator of ideas and support Members working together to deliver a successful Fourteenth WTO Ministerial Conference (MC14) in March 2026 in Cameroon”.33 Moreover, the APEC members expressed collective support for the Investment Facilitation for Development (IFD) Agreement and called for its integration into the Organization’s legal framework.34 Despite its voluntary and non-binding nature, APEC has a track record of being an idea incubator for advancing cooperative initiatives on many fronts ranging from supply chain connectivity and structural reform to good regulatory practices and the digital economy. This creates opportunities for cross-fertilization between APEC and the WTO.

The road ahead for the international economic system is fraught with challenges, making the principles enshrined by APEC more important than ever. Open regionalism provides a powerful antidote to protectionism and market fragmentations. The entity’s role as a platform for building consensus and discovering mutual benefits remains crucial. By upholding these values, APEC can help regional economies navigate this uncertain era and foster a more cooperative economic landscape. The longer-term effects of the complex interplay of multiple forces on the future economic system will be explored in greater detail in Chapter 2.

33 The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) (2025). The 2025 APEC Ministers Responsible for Trade Joint Statement, Jeju, Republic of Korea, May 16.

34 APEC (2025). “APEC Backs Global Push for WTO Investment Facilitation for Development Agreement”. News Release, May 13, https://www.apec.org/press/ news-releases/2025/apec-backs-global-push-for-wto-investment-facilitation-for-development-agreement

Different subregions possess divergent perspectives (Figure 1.7). For instance, 73% of respondents from North America choose “increased protectionism and trade wars” as their “most serious risk”. This may be because this subregion houses the economies most exposed to the US market. For example, Mexico’s and Canada’s goods exports to the US account for 28% and 19% of their GDP respectively. Also, 62% of survey subjects from Northeast Asia and 61% from Oceania consider the issue as their “most serious risk”, indicating serious concerns. This may be because the US remains one of their major trading partners.

Different subregions possess divergent perspectives (Figure 1.7). For instance, 73% of respondents from North America choose “increased protectionism and trade wars” as their “most serious risk”. This may be because this subregion houses the economies most exposed to the US market. For example, Mexico’s and Canada’s goods exports to the US account for 28% and 19% of their GDP respectively. Also, 62% of survey subjects from Northeast Asia and 61% from Oceania consider the issue as their “most serious risk”, indicating serious concerns. This may be because the US remains one of their major trading partners.

A close look at the PECC survey reveals that perspectives on inflation differ across subregions (Figure 1.12). Southeast Asian and North American individuals are most concerned, with 67% of the former and 65% of the latter pick it as their risk to growth.

A close look at the PECC survey reveals that perspectives on inflation differ across subregions (Figure 1.12). Southeast Asian and North American individuals are most concerned, with 67% of the former and 65% of the latter pick it as their risk to growth.

The PECC survey uncovers cross-subregional variations (Figure 1.15). Respondents living in Pacific South America and Oceania are the most worried. About 60% of these individuals cite the issue as their risk to growth, as compared to about 36-42% of their counterparts elsewhere. This result may be attributed to the two subregions’ unique geographical vulnerabilities. Illustratively, Oceania has several low-lying islands or communities. Rising sea levels cause coastal erosion and freshwater contamination, threatening their livelihood and existence.

The PECC survey uncovers cross-subregional variations (Figure 1.15). Respondents living in Pacific South America and Oceania are the most worried. About 60% of these individuals cite the issue as their risk to growth, as compared to about 36-42% of their counterparts elsewhere. This result may be attributed to the two subregions’ unique geographical vulnerabilities. Illustratively, Oceania has several low-lying islands or communities. Rising sea levels cause coastal erosion and freshwater contamination, threatening their livelihood and existence.

“Rising economic inequality within societies” emerges as the third most important concern about trade and globalization, with 68% of survey subjects choosing it (Figure 1.18). The issue has worsened in the past three decades. During this period, income inequalities in more than half of all economies and close to 90% of advanced ones were widened.23 This phenomenon may be explained by various elements ranging from new technological innovations, unequal access to finance, to stringent labor markets.

“Rising economic inequality within societies” emerges as the third most important concern about trade and globalization, with 68% of survey subjects choosing it (Figure 1.18). The issue has worsened in the past three decades. During this period, income inequalities in more than half of all economies and close to 90% of advanced ones were widened.23 This phenomenon may be explained by various elements ranging from new technological innovations, unequal access to finance, to stringent labor markets.