CHAPTER 2 - AN ASIA-PACIFIC AGENDA FOR THE DIGITAL ECONOMY

Dr. Mari Pangestu and Dr. Peter Lovelock

INTRODUCTION

Internet-based technologies are rapidly changing the way in which businesses, consumers and governments interact with each other. The extent to which this transformation is taking place is leading some to conclude that the digital economy is not only the future of our economy, it is the economy. Goods and services are being digitized, not only in how they are developed, but also in how they are delivered and consumed, transforming how the economy works, and how individual sectors, such as health, education, security, finance, and even governance, work.

Some refer to the process as ‘digital DNA’2 - referring to how information and communication technologies have become the underlying, or fundamental building block, driver that is changing business models, the way in which the economy and government work, and the way people live. At one level it is about how billions of everyday online connections among people, businesses, devices, data, and processes are being connected, re-connected, and constantly interacting in a word, hyper-connectivity. It is about converting things in the physical world to a piece of information, a digital representation. But to convert the physical to the digital, requires having the basic infrastructure: affordable, open and safe hyper-connected access.

The pace and extent of this change varies both among and within economies. This is a result of both the underlying infrastructure and of the integrated policies put in place to develop the digital economy. Some economies in the APEC region, for example, have very high internet penetration rates while others are still lagging. Moreover, within economies, rural and low-income groups are often less well served raising the risk of a growing digital divide. The recent UN Broadband Commission “State of Broadband” Report notes that while 48 percent of the global population (3.6 billion) is online, internet penetration in the developing world is projected to reach only 41.3 percent by the end of 2017. There is also a gender divide, with men still outnumbering women in terms of internet usage, and the gender divide is becoming wider in many developing economies.3 Policy discussions tend to revolve around addressing ‘the backbone’, but in addition to ensuring that backbone access is there, it is now very apparent that at the heart of a digital economy is the absolute need for the backbone to be a platform that can interoperate with all other platforms both within an economy and between different economies.

The current pace of change offers enormous opportunities for more inclusive growth; potentially even providing the opportunity for economies to leapfrog stages of development by promoting more inclusive access along with economic and social participation. Previous development models required enormous capital expenditure. Digital technologies at reasonable cost – especially mobile-enabled interoperable platforms – open opportunities for previously underserved communities to engage in broad ranges of economic activities through the provision of access. For example, healthcare and banking services can now be provided without the need for building new physical infrastructure, or even having practitioners or service personnel on location.

The digital economy is also changing the nature of business. In the past the corporation was the center of the commercial system; now increasingly it is the individual. This throws into question how governments and societies are organized and the way in which value is created. There is a certain degree of ambiguity on the nature of service providers such as Uber, Didi, Grab, Airbnb: are they taxi and hotel firms, transportation and hospitality businesses, or are they software companies? Are they platforms? This is neither a banal or a semantic series of questions. Is the driver of an Uber car an Uber employee or self-employed? Such designations can have profound implications for the tax system, for labor protection and the social security system. As we look to progress the digital economy therefore, a further and perhaps fundamental challenge lies in how we deal with the consequences of the associated disruptions, and to create a trusted environment to cooperate globally.

Three immediate questions for policy makers and trade officials are thus apparent:

• What is the digital economy and what are its implications?

• What are the opportunities and risks?

• What are the implications for local, domestic and international policy?

DIGITIZATION: REDUCING FRICTIONS, INCREASING TENSIONS?

Globalization is deeply intertwined with technological change. The first era of globalization began with the steam engine. Improvements in communications technology allowed regional production networks to evolve. Today, the digital economy is again reducing traditional market frictions. The time and the costs required to find information, to meet people, to access market data, to buy something, are all coming down. Moreover, while the previous era of globalization was about companies, today we are talking about individuals – micro and small enterprises benefitting from access to global markets.

Thus, individuals and small enterprises (often with outsized influence, or ‘power’), need to be collaborated with, if the platform economies are to be successful. But for this transition to be successful and sustainable, those being collaborated with, need to be empowered to benefit also. For the Uber platform to be successful, the consumers need to want to consume from the platform, and the drivers need to want to participate. And, not only now, but on an ongoing and sustainable basis. This is true too of the Khan Academy platform, the YouTube platform, and so on. If customers, consumers, participants, traders do not feel that they are benefitting and empowered, if they instead feel exploited, or increasingly insecure, then the welfare gains will prove to be shortlived and unsustainable.

This means that it is not enough to have physical connectivity. Looking at Indonesia as an example, it may appear to be one of the most highly connected economies in the region. As the fourth most populous Facebook community, and the “Twitter capital of the world,” Indonesians have adopted new technology usage at a rapid rate. However, not only is such connectivity highly and disproportionately concentrated on urban or wealthier environments, the connectivity itself is disproportionately focused on social media and social connectivity – some 80-90 percent of digital activity – with far less usage directed towards economic, trade or social development activity. And thus, Indonesia’s connectivity hasn’t been translated into significant economic value yet. Developing in parallel the human capacity to use connectivity to have and to generate economic value – that is, true digital literacy - is a requirement.4

This points to the issue of governance and the need to rethink both the approach and the coordination mechanisms required to create a successful digital economy framework. It also points to two further complicating challenges in the digital era: regulation and cross-border trade.

As has been repeated in many different contexts, the Internet knows no borders. This is a strength in providing access to a global market, in lowering costs, and in accelerating and democratizing innovation. But increasingly the challenges are becoming apparent: differences in the levels of market development when coupled with digital opportunity have rapidly challenged the ability of policy makers to effectively control policy and regulatory levers in everything from cybersecurity to privacy, piracy, tax regimes and even identity. The ability of domestic policymakers and regulators to stipulate and enforce decisions has been challenged and eroded. The recent release of the latest Apple iPhone has again brought into stark relief the opportunities that become apparent with a digital – and therefore global – footprint, and the practical enforcement requirements that emerge alongside the opportunities. Every new Apple product line announced on September 12 was given the same price in pounds sterling and dollars, from the cheapest Apple TV (£149 or $149) to the most expensive iPhone X ($1,149 or £1,149) – this despite a 25 percent foreign exchange difference between the dollar and the pound. Numerous articles pointed out that this made it potentially cheaper for a UK resident to fly to New York and buy an iPhone than at home. But to do so, even for personal use, is illegal.5

Similar issues are emerging in multiple domains accelerating the requirements for cross-border accountability. But does this also mean cross-border enforcement and cross-border regulation? And, if so, how? It is clear that we need to not only promote but to ensure cross-border data flows, and to make these as seamless as possible, but how to enforce such requirements? And, how to promote such benefits domestically and the necessary cooperation internationally?

What has become increasingly clear is that at the domestic level this requires a fundamental change in approach to regulation, and a change in the mindsets and the capacity of the regulating authorities. Beyond being a risk manager, and an enforcer of sectoral regulation, the regulating authority needs to become an advocate for, and an enabler of, digital inclusion and innovation. Thus, one of the first steps to promoting digital economy growth needs to be in understanding the disruptive challenges of the digital economy to sectoral regulation, and providing regulators with the tools to manage these disruptions rather than blocking them.

CHANGING BUSINESS MODELS?

The accelerating pace of technological change in recent years compounds these challenges and the pressures upon policymakers and regulators: beginning with the internet, followed by the disruption of the Web and later the App economy, and most recently the development of cloud computing and platform economies. These waves of change progressively extended access at fractional cost, with greater flexibility to act and respond to consumer demand.

The digital economy is also changing economic systems6 to become increasingly peer-to-peer, i.e., crowd-centric rather than corporatecentric, as noted above. Airbnb, for example, has some 640,000 hosts and two million available spaces in 34,000 cities under active consideration, without the corporate body owning a single piece of property. This crowd-centric model challenges our existing notions of employee and employers, hence the emerging regulatory and legislative grey areas regarding whether Uber is or isn’t a transport company: are Uber drivers working for a company or are they partners? Do they have worker rights? If not, then what kind of rights do they have? These are not one-off questions but are arising with increasing frequency across sectors as platform economies move more and more into mainstream commercial activity. To date, the income growth, or at least the income opportunities, for people working in this space have been quite tremendous. But is that always the case, and as more people move into the space and the platforms look to maximize profits, will income growth stay positive? Fundamentally: is this a case for the market or for regulators? And how should regional trade officials be looking at such developments?

An Asian example is Go-Jek, providing motorcycle taxi rides in Indonesia. Within just three years, the operation has grown to 300,000 drivers earning an average of four million rupiah per month – double the minimum wage. Moreover, having started out with ride sharing services, the company has used the same platform to provide an increasing multitude of other services that “share” under-used access to idle resources, including Go-Food, Go-Massage, Go-Glam, and most recently payment services through Go-Pay.

Together, these developments are transforming business models. In particular, the digital economy overturns our concepts of ‘the uneconomic citizen’: someone for whom the cost of connectivity, of being put onto the network, is simply not justifiable because of meagre economic and social returns. With the communications networks now a ‘horizontal’ enabler and not simply a ‘vertical’ sector, the benefits generated from providing someone with network access include the education, healthcare and broader participative (voting, welfare dissemination, tax, etc.) rights that accrue. This is because interoperability of networked platforms can enable all manner of service delivery: e-education, e-government, e-health, and so on, and in so doing transform almost all sectors, including agriculture, aquaculture, energy, logistics, and transportation.

INCLUSION

In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis the need for future growth to encompass both inclusiveness and innovation was emphasized by APEC leaders. Innovation inevitably entails change, but so too does inclusion, as the existing business models which see certain parts of the community as ‘uneconomic’ need to be challenged.

The impact of recent technology change, and particularly of cloud computing, has been to enable access to enterprise grade tools for micro and small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) at fractional cost. Thus, small businesses, like big enterprises, can now increase or decrease technology deployment as needed and without incurring sunk costs. When combined with mobile access, it has made business models supporting for example, remote healthcare and distance education (or MOOCs), not only feasible, but sustainable. No longer are such programs being driven solely by donor organizations or as corporate social responsibility programs. Hence fintech, healthtech, edutech, and so on, have emerged, targeting market gaps or failures.

Moreover, it is not just the private sector, but government too that has been enabled to take advantage of the outsourcing of technology cost while retaining the innovation benefits, extending government reach and enabling the timely delivery of all kinds of services.

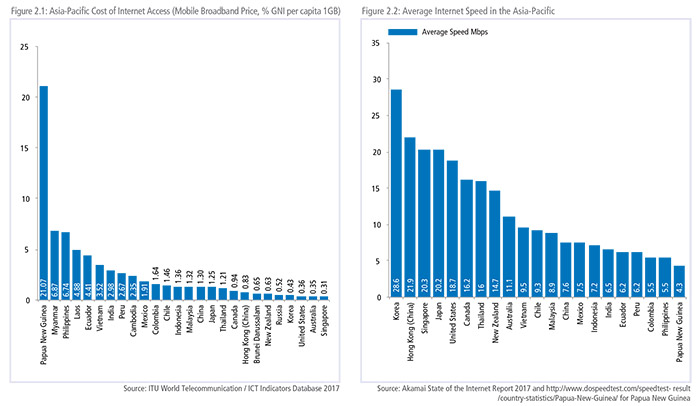

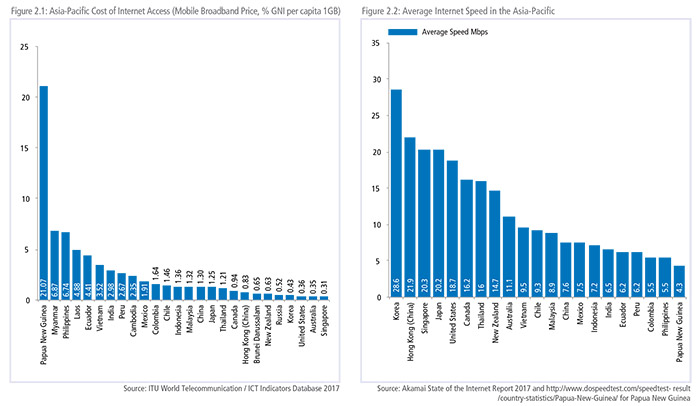

Given the opportunities from the digital economy, access to the internet needs to be improved, especially for emerging economies and remote areas. However, as was already mentioned above, it is not simply about access. Accessibility has to be affordable, secure, reliable and fast. As shown in Figure 2.1, the cost of accessing the internet varies considerably in the region but the costs as a percentage of GNI per capita, are considerably higher in emerging economies which also tend to have lower average internet speeds.

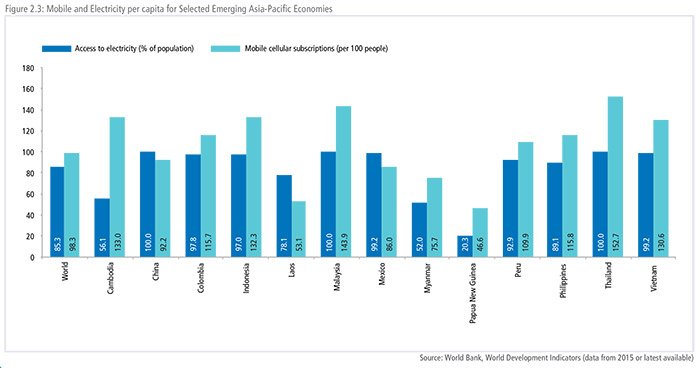

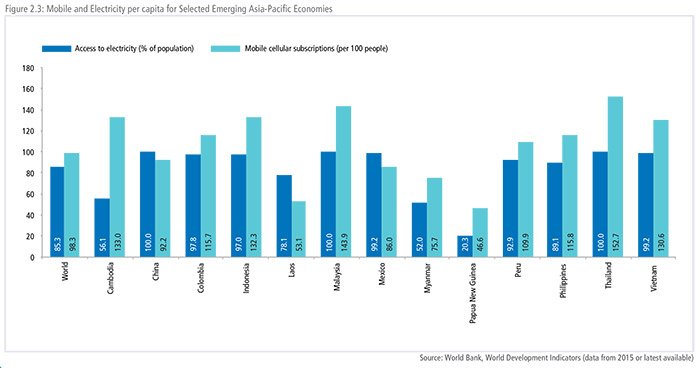

Moreover, while there has been an extremely successful ‘mobile first’ trend with many users first accessing the internet only through mobile, this also requires having electricity. Electrification rates are lower than mobile penetration. Emerging economies should therefore deal with three issues sequentially and if possible in parallel: electrification, telecom infrastructure, and the cost of access to smartphones.

DIGITAL ECONOMY AND JOBS

The impact of the digital economy on labor markets will be large. Routine and more mechanical type of works are already being replaced by machines, by automation, by robots, and by systems. This means that workers need to be transitioned to jobs that are either of low productivity but with some complexity, or increasingly to higher productivity tasks. This is emerging as a significant political issue for many economies, and is only likely to increase dramatically in the near future unless policymakers begin to plan for and promote such transitions. For example, in the United States, estimates suggest that from 2000 to 2010, some 85 percent of jobs

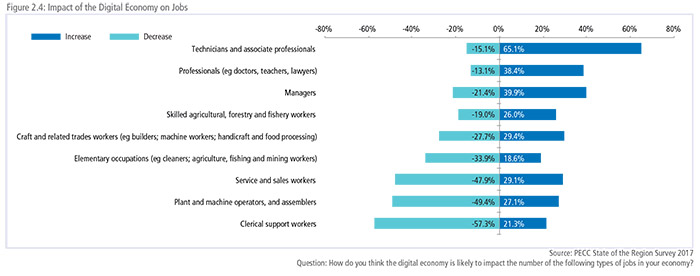

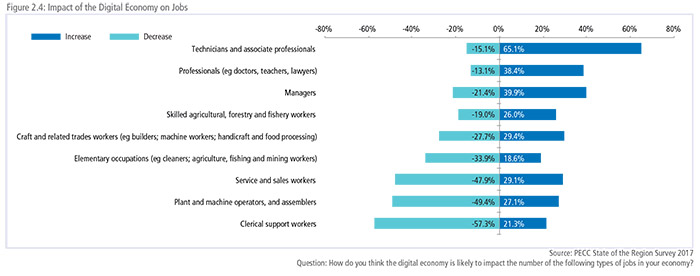

lost were due to productivity gains and on average only 13 percent of job losses due to trade competition.7 The ILO, among others, is attempting to track the impact on jobs resulting from automation and the so-called 4th industrial revolution, but without proper, consistent, and comparable measurements of the digital economy it remains a fraught task. According to the results of PECC’s 2017 State of the Region survey, while people expected some types of jobs to decrease, such as clerical and assembly line work, others were expected to increase such as technical and professionals. Those jobs expected to increase tend to be associated with higher levels of education but not necessarily those with university degrees.

EDUCATION

Education has been seen by many to be the last information-based industry to undergo a technological revolution. Before the digital economy a single teacher was limited to teaching in a physically defined classroom. Today that same teacher can reach, hundreds or thousands online. In some cases, as with viral YouTube or TED lectures, the online audience can be in the millions. And online teaching is proving to be extremely effective.8

Udacity, for example, will refund their graduates 100 percent of tuition from certain streams of their courses if they don’t secure a job at Facebook, Google, Oracle or similar firms. There are studies showing that 71 percent of chief academic officers in US institutions now view online teaching as being “equal to, or better than, ‘offline’ courses” at many institutions. Thus, the challenge is no longer one of results and recognition – top ranked universities are increasingly recognizing units taught online so that students can study via these channels and secure a full degree.

More importantly in many parts of the region is the use of technology to resolve accessibility issues for education. For example, Bridge Academies provides a good quality curriculum of studies for $6 per month, which includes the provision of tablets as the access device. This model is being scaled across India and Asia, as are a variety of others both similar and distinct. Facebook has been attempting something similar with its variously named ‘zero package’ initiative in several economies. Smart phones are provided for $39 and connectivity is free within a certain ‘selected garden’ of content. While these initiatives have proved to be controversial from a competition and net neutrality perspective, with many questioning Facebook’s motivations, the model aims to enable everybody to access online internet content – including education.

On the teachers’ side of the equation, online education platforms are helping to address the lack of qualified teachers by extending the access and reach of qualified and talented teachers, and in so doing are creating online ‘superstars’ in the education profession – teachers making millions of dollars a year teaching. Platforms are now available that allow a teacher to log on during their spare time and teach for even just a few minutes. One initiative for example, brings in retired teachers to teach children English, leveraging underutilized capacity and creating a market. It also enables teachers to focus on just teaching, while grading, administration, class preparation and of course materials can be outsourced.

THE POLICY AGENDA

Given the above trends and developments in digital economy in the Asia-Pacific region, we need to continue to prioritize capturing the potential of digital dividends and digital development as broadly as possible. The digital economy, if successful, can promote efficiency, innovation, and inclusion9. The lower cost of accessing and utilizing ICT makes economic activities more productive and innovative, for example enabling farmers to get information on the weather, their own field and crop conditions and watering requirements, and on market prices, while SMEs can get access to e-commerce platforms. Public services can be improved leading to better governance and, potentially, better democracy.

As in previous phases of globalization, there is a tendency to try to ‘protect’ the domestic development of the data economy or the digital economy. In the past this took the form of tariffs on goods or services trade, today these protectionist moves often focus on requiring data to be processed or stored locally, and creating other restrictions of data flows. Increasingly, the blocks to free trade are centered upon data flows.

But data has different characteristics from traditional goods and services. While the value of data can be difficult to define (and this is in itself a topic now attracting a lot of attention), there is little doubt that the value of data overall is increasing as data networks continues to grow.

This focus on data is, for example, changing the thinking around comparative advantage with the focus shifting, on the one hand, to the individual, as noted above, and on the other, to new forms of collaborative enterprise. Simply put, the people who need the data have to collaborate with those that have the data. Thus, telecom firms are taking on some banking functions, airlines are working with crowd-sourced accommodation providers, and so on.

Emerging from this are new and complex questions around the ownership of data, around data privacy, protection and access, and around data security. Three policy issues that have yet to be properly addressed at either the domestic or international levels are: cloud computing, data localization, and cyber security. But there are also questions around the changes in the nature of competition with “the winner takes all” business model, around market participation and tax issues. There are emerging and fraught questions on the accuracy of data and of information: with so much information available – some of it real, other information perhaps less so – is it now more difficult to ensure the reliability and authenticity of information?

So, some questions for thought in developing the necessary policy framework can be identified: How can we have systems that establish trust in cross-border transactions? How can we capture the gains from trade and investment in a data driven environment? Avoiding the costs of data localization policies, particularly for local firms, is very much a trade argument, and yet this has not begun to be dealt with by trade policy officials. The stalled Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement framed some of these issues, but even in as forward looking an agenda as that, it remained light on details. Then there are the security and privacy issues.

These challenges are very real, and as we have seen with developments such as the WannaCry malware, the Equifax data breach, and the Swift cybertheft of up to USD1 billion from a Bangladesh bank. All these events imply that immediate thought and, preferably, some increased degree of cooperation is much needed. However, given the potential for harm resulting from poor regulation or uniformed regulatory application in such a dynamic and nascent period, should regulators actually regulate or should we be relying more on self-regulation, as with for example, trip advisories which provide information on service providers, and allow people to rate, rank or yelp without there being a regulator? Instead, what we are seeing now is the emergence of a lot of protectionism – because regulators faced with uncertainty often try first to regulate to protect.

AN ASIA-PACIFIC AGENDA

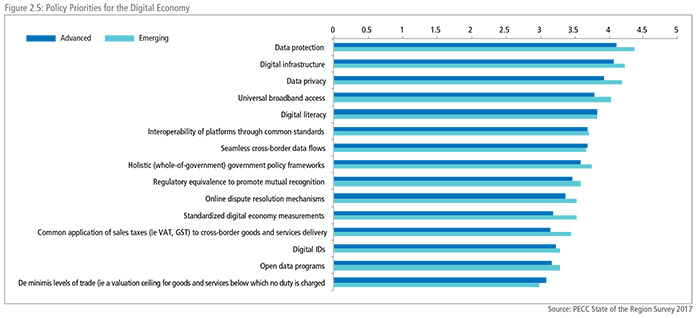

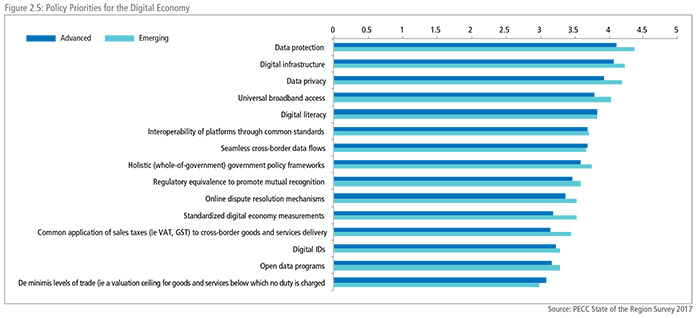

APEC could play a significant role in addressing these issues, precisely because of its convening and coordinating role and its nonbinding nature. To begin with, APEC could, and should, establish principles for the digital economy that individual economies could then review and implement. This would be much like the work APEC did to socialize investment and competition policy in the 1990s. As shown in Figure 2.5, there was little disagreement among respondents from emerging and advanced economies on the priority issues that need to be addressed for the growth of the digital economy.

One finding from the PECC survey is that respondents from emerging economies tended to give a slightly higher degree of importance to all issues compared to those from advanced economies. Indeed, the only issue on which respondents from advanced economies gave a higher degree of importance was on de minimis levels of trade. As discussed above, given the cyber attacks that have taken place in recent months, respondents from both emerging and advanced economies gave a high priority to data protection and privacy issues. This should spark a higher degree of interest in initiatives such as the APEC Cross Border Privacy Rules Framework.

A few issues jump straight to mind given the preceding discussion. First, a ‘whole of government’ approach is needed. Some economies now have a digital or an ICT ministry. At the very least those responsible for ICT policy need to be coordinated or represented at a high level of government. The digital economy cuts across all aspects of the economy and therefore, there needs to have political understanding and political support at the highest level of government as well as technical expertise. This is critical to minimizing unintended consequences from policy decisions and regulatory application. The risks are large. Should governments formulate polices on the basis of the interests of one sector of the economy, the risk is missing out on the development of new growth sectors.

Given the rapid pace of change taking place, the temptation as we have seen is for regulators to immediately step in to set market place rules. The problem is that the regulations tend to favor established interests, reducing the potential for innovation. This is not to say that there should be a free for all, simply that because of potential, but rather that the impact of innovations in markets and on consumers’ needs to be better understood. To this end, some economies are deploying ‘regulatory sandboxes’. Sandboxes permit innovators to pursue their businesses, working with regulators to enable greater understanding of both the technology and the business model, providing safeguards (minimizing systemic risk) before establishing regulations and placing new products or services under regulation. A number of financial regulators around the world have adopted the sandbox approach to launch innovative financial products that have extended inclusion or driven greater opportunity. The purpose of the sandbox is to minimize legal uncertainty; improve access to investment; adapt to test and learn approaches; and create rules for new products and services. These measures involve relaxing specific legal and regulatory requirements for new innovative products and often for a period of time, that market players would otherwise be subjected to.

Another critical ingredient is ‘trust’: how do governments build trust into the adoption of the new systems. One critical ingredient that needs to be looked at proactively by APEC economies is to have digital identification (ID) programs. Ideally, such a system would resolve to a single number or indicator that would be able to travel across both domains and jurisdictions. Without a digital representation, an individual can’t be connected in this hyperconnected world. But equally, many connected individuals now have multiple online identities (passwords, numbers, accounts, passports, etc.) which are not interoperable and often not interconnected.

Cross border e-commerce is a trade facilitation issue requiring harmonization of customs regulation and logistics for last mile delivery. The APEC SME Working Group has an SME Online to Offline (O2O) initiative to help promote SME trade engagement. While the Asia-Pacific region has become the fastest growing market for the digital economy, only a relatively few SMEs in APEC are currently taking full advantage of new digital opportunities. Relatedly, another area for international cooperation in the digital economy is in cross-border payment systems. This again depends on the sharing of data across platforms and across jurisdictions, so a logical starting point could be in trade finance – where much of the data is already shared.

Talent, human capital, capacity, and the future of jobs also need to be addressed. We need to consider the training and recruitment of workers, identifying the future skills needs, developments required, and of course, the tech education programs. APEC meetings, especially the Human Resources Development Working Group, already have programs on digital literacy and education. But how connected are these to other digital development and digital economy work programs? How well suited are they for the future opportunities and, importantly, do they address the need for the movement of people – talented and otherwise – around our region?

INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION

International trade discussions and agreements are slowly beginning to address rules for the digital economy. The Trans- Pacific Partnership included rules on the free flow of data across borders. Not all APEC members were part of the TPP negotiations so one part of the cooperation agenda would be to understand what such rules mean for the other economies. Similarly, the WTO has a temporary moratorium on the imposition of customs duties on e-commerce. There are moves to make this a permanent feature of trade rules – the TPP text agreed to this but other economies need to consider what the impact would be if such an arrangement were to become permanent. The TPP also dealt with a commitment to not require source code of software, and data localization.

The future of these policies agreed to in the TPP remain in the balance. Should TPP-11 or another variation of TPP proceed, it would set some international baselines among a still significant group of economies. Another approach advocated is to consider the TPP as an “organ donor”, that is for the text to be imported into other agreements with modifications or adjustments in accordance to the needs of the members.

CONCLUSION

Much of the ground we have covered has been addresssed in previous policy papers such as the telecoms reference paper. Many of the elements of the international policy regime needed to facilitate the growth of the digital economy already exist. The first imperative should be to build on and from those regimes, without becoming hidebound to them. Some progress has been made among groups of economies such as the TPP negotiating economies. But given the potential of the digital economy to promote inclusive and innovative growth, policy makers need to move much faster. The stakes are large – the sector is estimated to already be at around US$4 trillion.

A key principle is the need for flexibility and ongoing dialogue – but not at the expense of action-oriented steps. Technology is changing rapidly, and policies, frameworks, rules and regulations need to not just to have the room to adapt, but also to be agile. Agile implies that one has to be anticipatory, and be quick to respond and adapt in a continuous way since the changes are happening so much more rapidly.

The one final point worth making in this context is that for these developments to be successful requires trust. The process of building norms for the internet and digital economy will require bringing together regulators, politicians, businesses, negotiators and civil society to shape common understanding on these issues in a concerted fashion. APEC did this in the early 1990s on what were then difficult issues such as investment and competition policy; it needs to do so now for the internet/digital economy. In today’s terminology, we would call it “crowd wisdom.”