Section 2 - Prospects for transpacific natural gas trade

Energy use in Asia-Pacific economies

Compared to the markets in oil and coal, the natural gas market has traditionally been the least integrated, with the global market effectively segmented into three regions (Asia, Europe and North America) and trade largely occurring within these regions3. The scale of transpacific natural gas trade is particularly small in relation to global gas trade (0.3%), as opposed to 1.2% for oil and 4.6% for coal. Moreover, existing gas flows from North America to Asia were largely from the Kenai LNG export terminal in Alaska, which is scheduled to shut down later this year.

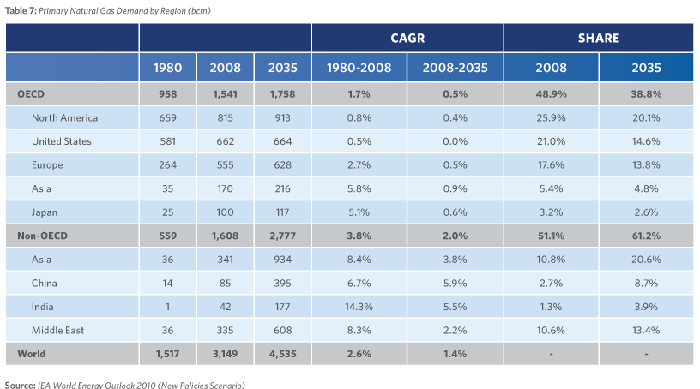

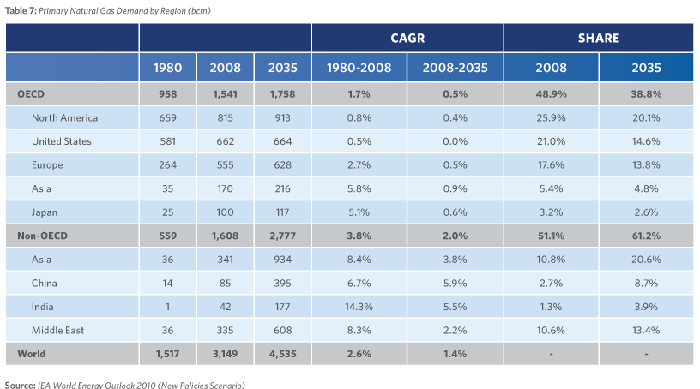

Recent developments in both gas demand and supply have led to a scenario where significant growth in LNG exports from North America to Asia has become a distinct possibility. On the demand side, natural gas demand in Asian economies is projected to grow substantially in the next 25 years, as Table 7 above illustrates. One reason is simply the strong economic growth forecast for Asia’s developing economies, in particular China and India, which consequently are expected to experience a higher than average CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) in gas demand of over 5%. Indeed, recent estimates of China’s future natural gas demand by the Institute for International Oil Politics are even more bullish, with demand projected to reach 450 bcm by 2020, compared to IEA’s estimate of 395 bcm by 2035. Moreover, the implementation of greenhouse gas policies, even at a modest level (as in IEA’s New Policies scenario), favors natural gas over other fossil fuels, which explains why the share of natural gas in Asia’s energy mix is expected to nearly double by 2035.

Two other factors could further boost Asia’s future demand for LNG imports. First, Indonesia and Malaysia, two of the largest gas exporters in the region, are both experiencing dwindling supply from aging fields. Coupled with increasing domestic natural gas demand, both countries appear set to be transformed into LNG importers. Indeed, Indonesia’s first import terminal is expected to begin operating in 2012, and private firms have already been given permission to import LNG. Malaysia has planned the construction of 3 LNG receiving terminals, and expects to begin importing LNG from 2014. As such, other Asian/Oceania economies that currently import gas from Indonesia and Malaysia may well have to scout for new import sources in the future.

Second is the impact of the earthquake in March this year on Japan’s LNG demand. The earthquake not only resulted in the shutdown of much of Japan’s nuclear generating capacity, in the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster, but also damaged oil and coal-fired thermal power stations. As Japan seeks to replace its lost thermal and nuclear capacity by running all its gasfired units, Japan’s LNG demand has increased and may be expected to continue to do so in the short-run. Whether Japan’s LNG demand will grow even further beyond the next 5 years is less clear- while Wood Mackenzie forecasts relatively flat LNG demand for Japan in the next decade, Ziff Energy expects strong growth in demand.

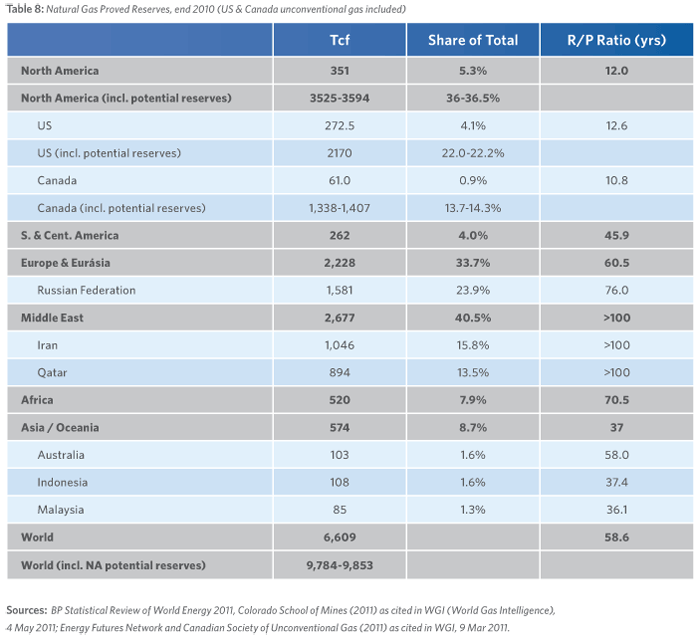

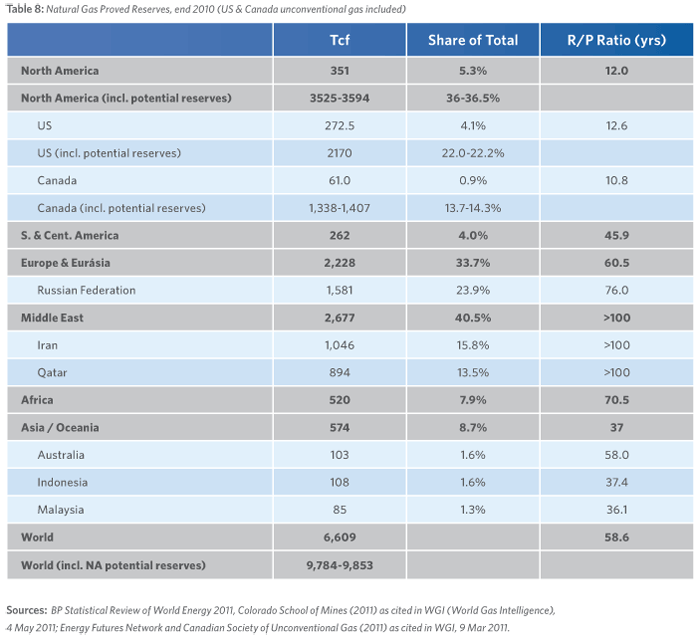

Growing demand in Asia for natural gas is also set to be accompanied by a large increase in North American gas production, driven by the shale gas revolution which has made feasible the extraction of vast reserves of unconventional gas in the US and Canada. An indication of the ‘game-changing’ nature of shale gas is provided by Table 8 below, which presents the proved reserves of natural gas at the end of 2010. While proved dry-gas reserves of the US only amount to 273 tcf (4% of the world’s total), the addition of potential gas reserves (as estimated by the Colorado School of Mines) inflates that figure to 2170 tcf (22% of the world’s total); shale gas accounts for 687 Tcf of that figure. Similarly, Canada’s recoverable gas reserves jump from 61 tcf to 1338-1407 tcf (14% of the world’s total) if unconventional gas reserves are included. Thus, whereas the US was once expected to be a major LNG importer, the EIA now expects US LNG imports to decline progressively as gas demand is increasingly met by domestic production.

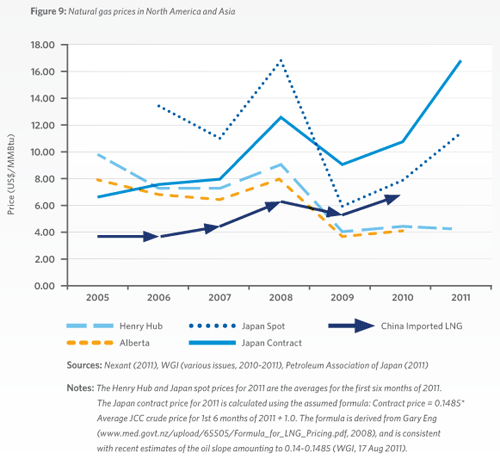

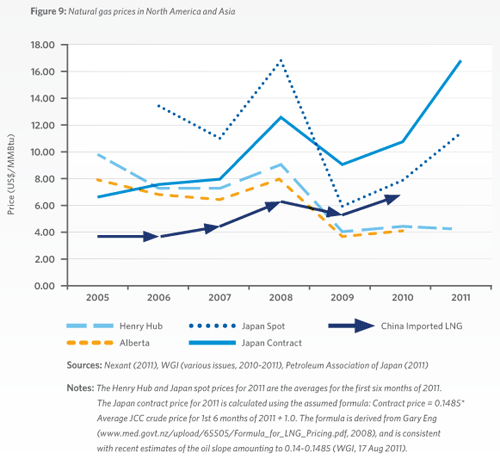

The effect of the North American gas glut coupled with the Asian demand surge has been to widen natural gas price differentials between North America and Asia. Historically, natural gas in the Asia-Pacific region has been priced at a premium relative to North American natural gas (see Figure 9). Several factors have contributed to the Asian premium- the absence of multiple import sources, the fact that gas is purchased under long-term contracts and finally the use of oil-indexed formulas to determine the prices of natural gas contracts. As Figure 9 illustrates, however, in the last few years the price differentials have widened considerably. The difference between the Japan contract price and the Henry Hub price in 2010 was approximately $6.40, and is estimated to have increased even further in 2011 to around $12.50 due to the oil price hike as well as the increase in Japan’s LNG demand following the Fukushima

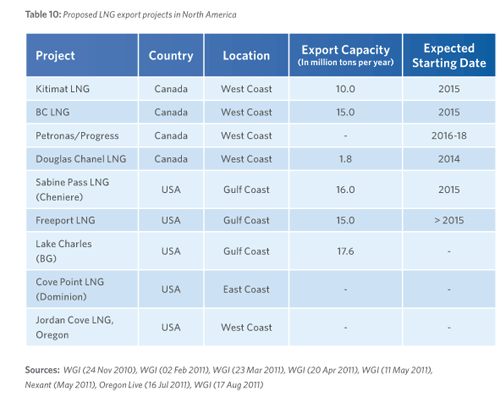

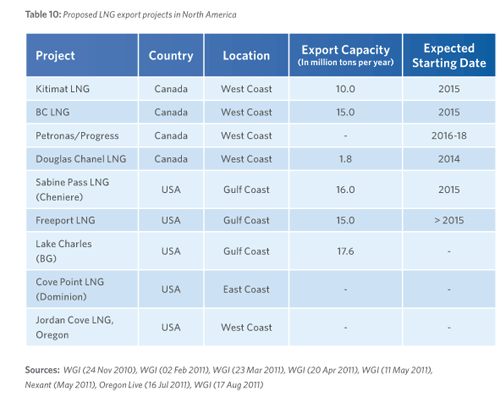

The effect of the North American gas glut coupled with the Asian demand surge has been to widen natural gas price differentials between North America and Asia. Historically, natural gas in the Asia-Pacific region has been priced at a premium relative to North American natural gas (see Figure 9). Several factors have contributed to the Asian premium- the absence of multiple import sources, the fact that gas is purchased under long-term contracts and finally the use of oil-indexed formulas to determine the prices of natural gas contracts. As Figure 9 illustrates, however, in the last few years the price differentials have widened considerably. The difference between the Japan contract price and the Henry Hub price in 2010 was approximately $6.40, and is estimated to have increased even further in 2011 to around $12.50 due to the oil price hike as well as the increase in Japan’s LNG demand following the Fukushima  disaster. With such large price differentials, gas exports from North America to Asia are increasingly attractive to investors, resulting in a number of export projects in both the US and Canada (Table 10). All of the projects proposed in Canada are new terminals to be located on the West Coast in British Columbia, with access to the vast reserves of mostly unconventional gas in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB) that span over the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia. In contrast, the US export projects largely involve re-purposing existing import terminals on the Gulf and East Coast into bi-directional terminals that can both export and import LNG.

disaster. With such large price differentials, gas exports from North America to Asia are increasingly attractive to investors, resulting in a number of export projects in both the US and Canada (Table 10). All of the projects proposed in Canada are new terminals to be located on the West Coast in British Columbia, with access to the vast reserves of mostly unconventional gas in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB) that span over the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia. In contrast, the US export projects largely involve re-purposing existing import terminals on the Gulf and East Coast into bi-directional terminals that can both export and import LNG.

Sources: Nexant (May 2011), Platts (13 Apr 2011), WGI (various issues, 2011), Petroleum Association of Japan (2011)

Notes:

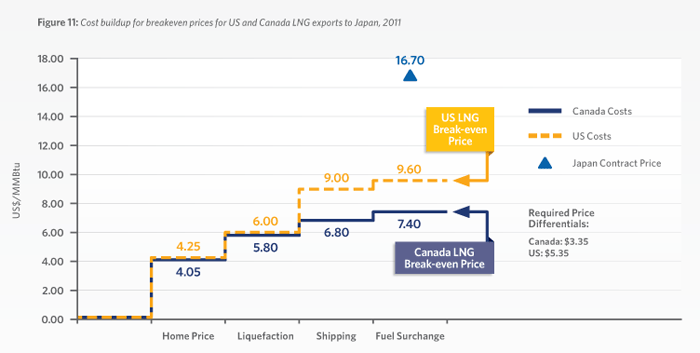

The Japan contract price and the Henry Hub price (i.e. home price for the US) refer to 2011 and are calculated as described in the notes to Figure 9. The home price for Canada refers to the Alberta average spot price for 2010 (Nexant, 2011). The costs of liquefaction, shipping and fuel surcharge are estimated by Barclays (Platts, 13 Apr 2011). The fuel surcharge is a fee paid to the hauler to cover the fuel costs incurred while shipping and is calculated as a fixed percentage of fuel prices so as to cushion the hauler from changes in fuel prices.

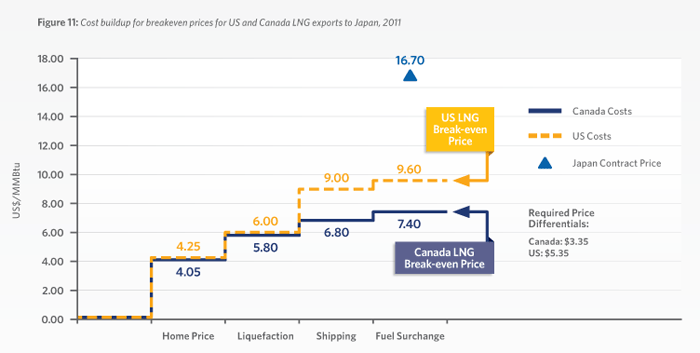

In evaluating the outlook for North American LNG export projects, a key question is whether exports from the USA or Canada to Asia are economically viable. The step-chart in Figure 11 illustrates the estimated prices at which LNG exported by US and Canada break even, and compares it to the actual price that LNG exporters can hope to obtain if they sell LNG to Japan under long-term contracts. At current prices, the break-even export price is approximately $9.60/MMBtu for US Gulf Coast terminals and $7.40/MMBtu for Canadian export terminals, both of which are considerably less than the estimated Japanese contract price of $16.70. Thus, at current prices it makes economic sense for gas producers in North America to export LNG to Asia as opposed to selling the gas domestically, with estimated profit margins of $9.35/MMBtu for Canadian exporters and $7.15/MMBtu for US exporters.

Independent of the price of natural gas in North America and Asia, it is estimated that US terminals will require a minimum price differential of US$5.35/MMBtu (between Henry Hub prices and Asian LNG prices) for US LNG exports to be economically feasible4, while the corresponding price differential required for Canadian terminals (i.e. the difference between Alberta prices and Asian LNG prices) is US$3.35/MMBtu. Canadian terminals (and any terminals on the US West Coast) thus have a substantial cost advantage over terminals on the US Gulf Coast due to the difference in shipping distances to Asia -- transportation costs for West Coast export terminals are only $1/MMBtu versus $3/ MMBtu for the Gulf Coast terminals. The impetus for Canada to export gas is also greater than for the US due to the presence of domestic push factors. Most of the gas demand in North America is in the U.S., and with US gas production increasing Canada’s gas exports to the US have been steadily declining.

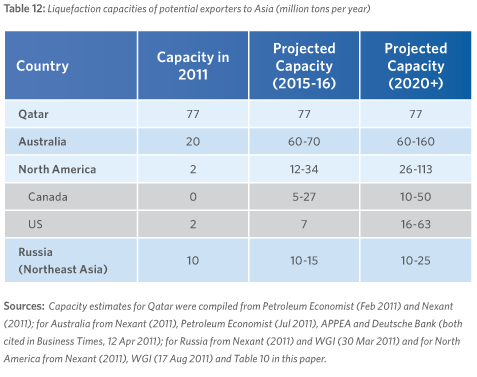

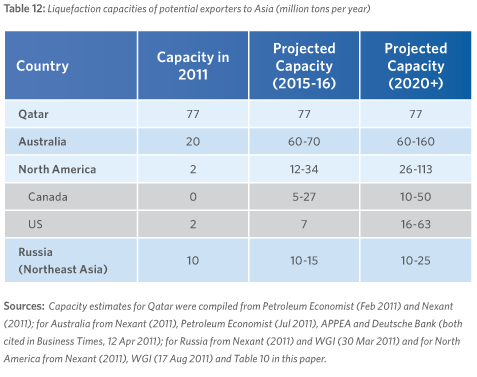

In view of the large reserves of unconventional gas in both Canada and the US (Table 8), there are unlikely to be any physical constraints on gas production. Liquefaction capacity, however, is the key capacity constraint. Projected liquefaction capacities of Canada and the US are presented in Table 12 together with those of Qatar, Australia and Russia (which are likely to be the other key competitors in the Asia-Pacific LNG market).

Despite the wide variability in the estimates, it is clear that the liquefaction capacity of Qatar and Australia will exceed that of North America in the medium-term (i.e. up to 2016) and quite likely in the long-run as well. Nevertheless, even conservative estimates of North America’s liquefaction capacity represent a sizeable chunk of the total liquefaction capacity that is to be used to direct LNG exports to Asia5. Thus, the possibility of profitable exports to Asia, coupled with growing liquefaction capacity, underscores the significant potential for large volumes of transpacific gas trade.

Despite the wide variability in the estimates, it is clear that the liquefaction capacity of Qatar and Australia will exceed that of North America in the medium-term (i.e. up to 2016) and quite likely in the long-run as well. Nevertheless, even conservative estimates of North America’s liquefaction capacity represent a sizeable chunk of the total liquefaction capacity that is to be used to direct LNG exports to Asia5. Thus, the possibility of profitable exports to Asia, coupled with growing liquefaction capacity, underscores the significant potential for large volumes of transpacific gas trade.

The actual volume of transpacific LNG trade in the mediumterm may be constrained by the cost advantage of existing LNG suppliers such as Qatar (and to a lesser extent, Australia), who have the luxury of reducing their prices to aggressively compete against North American exporters as well as the “first mover” advantage of existing suppliers to enter into long-term contracts for the rapidly growing demand for LNG, especially for Japan, in the wake of the Fukushima disaster. However, a desire for energy security on the part of Asian buyers might lead to significant North American LNG exports despite higher prices compared to existing supplies. Buying North American gas would allow Asian buyers possibilities for diversification by including multiple indices in their gas portfolio, and might further reduce risks for buyers given that North American gas prices (e.g. Henry Hub prices) are less volatile than the JCC crude price.

There are also regulatory risks in Canada and the United States related to environmental concerns around the hydraulic fracking process that is used in the recovery of shale gas, and opposition from large buyers of natural gas in the US, including Dow Chemical and American Public Gas Association, which have opposed LNG export plans on the grounds that they would lead to higher domestic prices and expose the domestic gas market to the potentially unstable global crude oil market.

Impact on gas and oil price differentials

Regardless of actual export volumes, the prospect of significant North American LNG exports is likely to have an impact on gas price differentials and oilgas price differentials in the region.

Asian LNG importers currently do not have access to a competitive market. Japan and South Korea source their LNG imports from a limited number of countries which hold significant market power. This market power is further enhanced by the pricing formulas of most long-term LNG contracts, which tie natural gas prices to the price of crude oil. While oil indexing was logical in the 1960s when natural gas used to be a substitute for home heating oil, natural gas today tends not to be a substitute for oil and the earlier logic behind indexation no longer holds. Instead, oil-indexed prices allow suppliers to assert their market power by charging high prices, partly because of high crude prices but also because such formulas can serve to aggregate the market power of a number of producers by providing an implicit collusive mechanism -- if all suppliers utilize oil-indexation (and crude oil prices are high enough), LNG prices will be maintained at high levels, to the benefit of all LNG exporters and LNG exporting countries.

Given the oligopolistic nature of the Asian LNG market and the high Asian gas price, the entry of North American producers into the Asian LNG market will challenge the market power of existing producers and threaten to capture some of their market share. At the same time, though, the break-even prices for North American producers are higher than those for producers from countries such as Qatar. In such a scenario, a rational response by existing producers will be to reduce the price they charge Asian buyers, so as to price North American producers out of the market while continuing to maintain their share of the market (albeit with lower prices and therefore lower profits). There are already indications that Qatari gas producers behave in the manner described above. In response to the growing threat of Australian competition, Qatar has recently reduced its price demands towards Japan even in spite of the post-Fukushima surge in Japan’s LNG demand.

One way Asian prices might decrease, in response to the entry of North American producers, is through adjustments to oil-indexation formulas (e.g. a decrease in the slope in a typical formula). What is unique about the North American gas supply push, however, is that it may eventually challenge the very basis of Asian LNG pricing- the use of oil-indexed formulas. North American gas prices are not oil-indexed and thus provide their own alternative benchmarks for pricing (e.g. Henry Hub pricing). Given the large differential between oil and gas prices in North America, prices of North American LNG based on gas-hub indices are likely to be much lower than prices determined using traditional oil-indexed formulas, which could lead buyers to increasingly explore alternative pricing mechanisms for contract LNG. Although oil-indexation formulas are likely to stay, if pricing based on North American gas-hub prices is adopted at some point in the future due to the influx of North American exports, Asian prices (and therefore price differentials between Asia and North America) are likely to fall, independently of whether sellers pursue a strategy of lowering prices in order to maintain market share.

Furthermore, price differentials can be expected to decline because of a potential shift in the balance between contract and spot LNG prices used by Asian buyers. While contracted LNG has been the traditional mainstay, a number of economies have recently demonstrated an increased openness to purchasing spot LNG. For instance, in the aftermath of the March earthquake, Japanese buyers have tended not to rush into new long-term contracts, relying instead on spot LNG and LNG from short-term contracts to cover up for lost nuclear and thermal capacity. North America’s entry into the Asian LNG market, by providing Asian buyers with an additional source of LNG supplies, might persuade them to buy a greater proportion of their LNG from spot markets. The fact that Henry Hub spot prices are far lower than contract LNG prices would mean that the average price paid by Asian buyers for their LNG would decline (even if contract prices remained the same).

<< Previous

Next >>

The effect of the North American gas glut coupled with the Asian demand surge has been to widen natural gas price differentials between North America and Asia. Historically, natural gas in the Asia-Pacific region has been priced at a premium relative to North American natural gas (see Figure 9). Several factors have contributed to the Asian premium- the absence of multiple import sources, the fact that gas is purchased under long-term contracts and finally the use of oil-indexed formulas to determine the prices of natural gas contracts. As Figure 9 illustrates, however, in the last few years the price differentials have widened considerably. The difference between the Japan contract price and the Henry Hub price in 2010 was approximately $6.40, and is estimated to have increased even further in 2011 to around $12.50 due to the oil price hike as well as the increase in Japan’s LNG demand following the Fukushima

The effect of the North American gas glut coupled with the Asian demand surge has been to widen natural gas price differentials between North America and Asia. Historically, natural gas in the Asia-Pacific region has been priced at a premium relative to North American natural gas (see Figure 9). Several factors have contributed to the Asian premium- the absence of multiple import sources, the fact that gas is purchased under long-term contracts and finally the use of oil-indexed formulas to determine the prices of natural gas contracts. As Figure 9 illustrates, however, in the last few years the price differentials have widened considerably. The difference between the Japan contract price and the Henry Hub price in 2010 was approximately $6.40, and is estimated to have increased even further in 2011 to around $12.50 due to the oil price hike as well as the increase in Japan’s LNG demand following the Fukushima  disaster. With such large price differentials, gas exports from North America to Asia are increasingly attractive to investors, resulting in a number of export projects in both the US and Canada (Table 10). All of the projects proposed in Canada are new terminals to be located on the West Coast in British Columbia, with access to the vast reserves of mostly unconventional gas in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB) that span over the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia. In contrast, the US export projects largely involve re-purposing existing import terminals on the Gulf and East Coast into bi-directional terminals that can both export and import LNG.

disaster. With such large price differentials, gas exports from North America to Asia are increasingly attractive to investors, resulting in a number of export projects in both the US and Canada (Table 10). All of the projects proposed in Canada are new terminals to be located on the West Coast in British Columbia, with access to the vast reserves of mostly unconventional gas in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB) that span over the provinces of Alberta and British Columbia. In contrast, the US export projects largely involve re-purposing existing import terminals on the Gulf and East Coast into bi-directional terminals that can both export and import LNG.

Despite the wide variability in the estimates, it is clear that the liquefaction capacity of Qatar and Australia will exceed that of North America in the medium-term (i.e. up to 2016) and quite likely in the long-run as well. Nevertheless, even conservative estimates of North America’s liquefaction capacity represent a sizeable chunk of the total liquefaction capacity that is to be used to direct LNG exports to Asia5. Thus, the possibility of profitable exports to Asia, coupled with growing liquefaction capacity, underscores the significant potential for large volumes of transpacific gas trade.

Despite the wide variability in the estimates, it is clear that the liquefaction capacity of Qatar and Australia will exceed that of North America in the medium-term (i.e. up to 2016) and quite likely in the long-run as well. Nevertheless, even conservative estimates of North America’s liquefaction capacity represent a sizeable chunk of the total liquefaction capacity that is to be used to direct LNG exports to Asia5. Thus, the possibility of profitable exports to Asia, coupled with growing liquefaction capacity, underscores the significant potential for large volumes of transpacific gas trade.