Chapter 1: Impact of the Covid-19 Crisis Update

Eduardo Pedrosa and Christopher Findlay

This year was supposed to be a milestone for the Asia-Pacific region when APEC members reached the target date of the Bogor Goals and agreed on a new vision to drive economic growth and integration moving ahead. The Covid-19 pandemic came perhaps as a black swan event. Not because it was a new virus per se, experts have been warning of the threat from viruses for some time, with SARS and MERS serving as just two prior examples, but because it was so infectious and spread so quickly around the world. We live in a world that is more connected than ever, this has brought tremendous benefits in terms of improved livelihoods, but the Covid-19 crisis has underscored the frailties of international systems of cooperation to address pandemics and our responses to them. We need to learn from this experience.

This report updates PECC’s Special Report on the Impact of the Covid-19 Crisis. That report was largely based on a survey of stakeholders and policy experts from May to June 2020. One finding from that survey was the significantly greater levels of pessimism on the economic outlook among respondents compared to official forecasts. While official forecasts have improved we highlight that growth remains supported by unprecedented government stimulus. That support remains crucial as does well-laid out exit strategy. The policy recommendations we laid out in our earlier report remain relevant and in this report we thresh them out in more detail.

One central recommendation was the role that a post-2020 vision can play in providing a framework for recovery. Without such a framework there is a risk that the recovery will be much slower than need be, opportunities to sustain reform will not be taken, inefficient policies adopted for short term goals will remain stuck in place, and investment plans put on hold. While APEC remains a relatively informal organization through which relationships of trust are built, it must allow for genuine dialogue at all levels.

A central role that APEC has traditionally played is building understanding on international trade and support for the multilateral trading system. Our survey results identified slowing trade growth and rising trade protectionism as the highest risks to growth over the next 2 years after the immediate problems of the pandemic and jobs. We provide a special focus on challenges facing the World Trade Organization at the moment.

The Covid-19 crisis is accelerating change, economies will be taking different approaches in response to it. For example in Chapter 2 we address the different choices being taken to address the digital economy, APEC provides an essential platform to exchange views on the motivations behind those policy choices and the international implications that they often have.

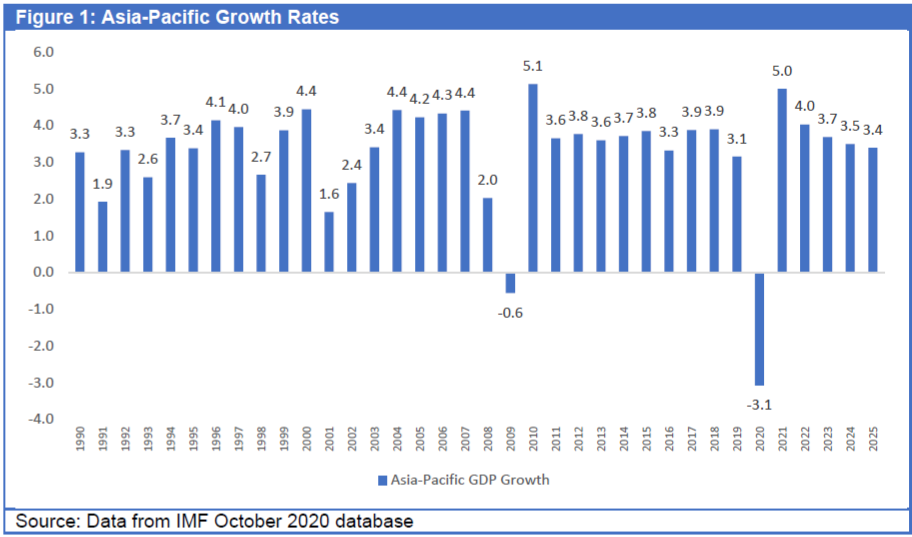

Economic Outlook

The economic outlook for the Asia-Pacific1 has improved somewhat in recent months, but recovery will be uneven and fragile as the global pandemic has deepened in some places. Asia-Pacific economies are expected to shrink by about 3.1 percent in 2020 – less than the 4.7 percent contraction forecast in July’s State of the Region Report: Impact of the Covid-19 Crisis. Growth of 5 percent is now expected next year (see Figure 1). Growth in the Asia-Pacific is then expected to decline towards 3.5% in subsequent years.

The reasons for the improved 2020 picture are China’s return to growth (it reported 4.9 percent expansion for the third quarter) and the less severe-than-expected downturns in several advanced economies.2 However, achieving significant and sustainable gains is contingent on reduced global volatility and on multilateral cooperation – which has been sorely lacking - to contain the global pandemic.

While the regional economy is coming out of the depths it fell to in the first half of 2020, the cost of the pandemic in terms of lives, sickness, livelihoods, and businesses is huge. Complicating matters, the Covid-19 crisis hit at a time the region was already facing an array of challenges. Among those spelled out

last year in PECC’s task force report on a post-2020 vision for the region were:3

- Urgent questions about the quality and sustainability of economic growth;

- Growing concerns about increasing inequalities in income and wealth distribution;

- Existential challenges of environmental sustainability and climate change; and

- Rapid technological change with the potential to both contribute to an acceleration of the spread of prosperity, but also to intensify social strains and tendencies toward fragmentation

These challenges have led to growing skepticism in some sections of Asia-Pacific societies toward the value of openness and interconnectedness. That undermines political support for regional economic cooperation, which in turn has complicated joint efforts to tackle Covid-19. This update will address some related concerns in dealing with the crisis as well as medium to longer-term issues. This agenda for cooperation includes restoring a sense of confidence in the future, that involves responding to the issues that had already beset the region before Covid-19 upended the world.

Big gains, big challenges

For a quarter of a century, regional economic integration and indeed growth have been driven by the vision set by APEC leaders when they first met in Blake Island in 1993 and then in Bogor in 1994 and agreed to pursue the goal of:

“free and open trade and investment in the Asia-Pacific no later than the year 2020.”

Given the manifold challenges facing the region and world today, it is worth remembering that the commitment to openness was not an ‘add on’ but was, at the time, central to APEC’s vision. Leaders also pledged that:

“our people share the benefits of economic growth, improve education and training, link our economies through advances in telecommunications and transportation, and use our resources sustainably.”

Such a vision is once again required against a background of fragile relationships and tenuous commitments to multilateral principles. The gains that the region has made in the pursuit of this vision have been impressive, average incomes rose from USD 10,258 in 1990 to USD 22,000 in 2017. In 1990, the highest per capita GDP in the region was more than 58 times the lowest; by 2017, this was down to 22 times.4

Even though the emerging economies now account for about 43 percent of regional GDP in current USD terms, over the next 5 years, they are expected to account for as much as 73 percent of the region’s growth. This process was recognized by APEC leaders in Bogor when they stated:

“the narrowing gap in the stages of development among the Asia-Pacific economies will benefit all members and promote the attainment of Asia-Pacific economic progress as a whole.”

The point is that the narrowing creates benefits for all members. Such a commitment to openness remains critical to the region’s future and the delivery of shared benefits that is in APEC’s DNA. On this platform we build other suggestion for cooperation. Over the period, annualized growth of consumption expenditure for emerging economies has been growing at about twice the rate of that of the region’s advanced economies.

A shift towards a greater role of domestic demand in driving growth has been a long-term trend in the region and an important part of rebalancing growth after the Global Financial Crisis. This is to do with longer term demographic trends, for example in 2019, McKinsey estimated that there “soon” would be about 3 billion Asian middle-class consumers.5 The impact of the Covid-19 crisis may slow that trend temporarily but in the longer term, the trend remains important, based on solid demographics and it will be an important changing structural feature of the Asia-Pacific economy.

The mutual benefits of this process is likely to change as the nature of flows change, from traditional goods to GVC networks to greater trade in services. APEC has begun to address these issues through its work on services and the digital economy. However, as with the earlier phase of the region’s liberalization, much of the reform that took place was seen as mutually beneficial – these were individual action plans, rather than negotiations. APEC provided a confidence building platform, and assurance that others were moving in the

same direction.

Stimulus Measures

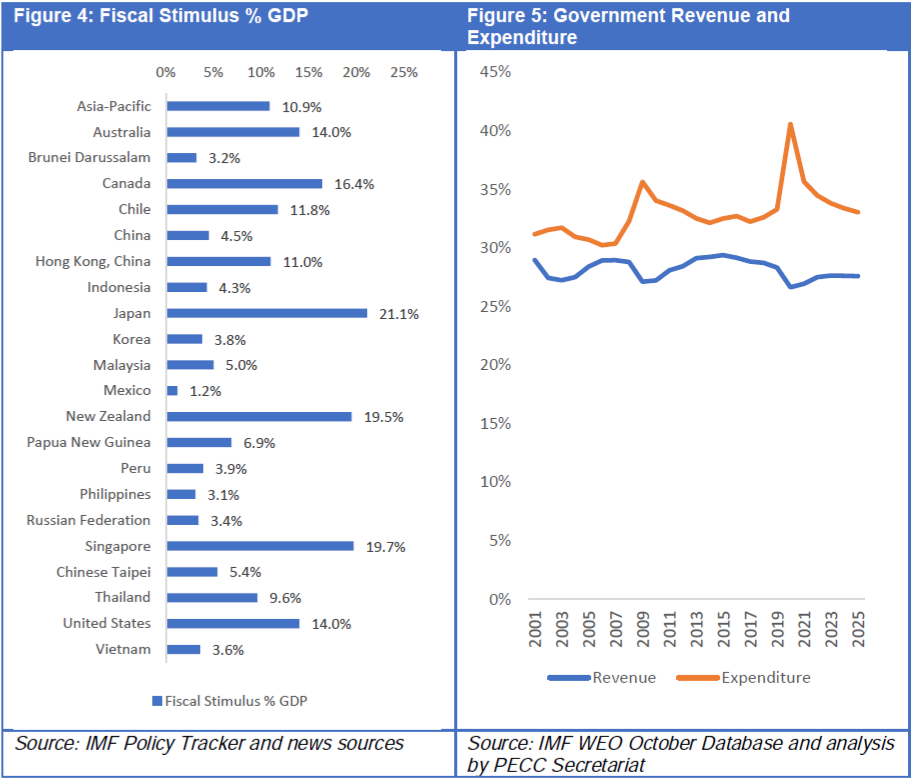

To counteract the supply and demand shocks associated with COVID-19, governments across the region have been implementing monetary and fiscal stimulus measures. These have prevented an economic freefall, saved millions of jobs and forestalled the possibility of a financial crisis. As seen in Figure 4, the percentage of stimulus has varied from economy to economy, from less than 1 percent to more than 20 percent of GDP.

In 2020, Asia-Pacific economies have implemented combined stimulus measures worth about US$6.0 trillion, or 11 percent of GDP and about half of all global stimulus.6 This does not include central bank funding nor support from what the IMF calls ‘below the line’ measures - loans and equity injections. Other examples have included easing insolvency requirements, arranging rent and bank loan reductions or repayment deferrals.7 In spite of the massive stimulus, there remain deep concerns in financial markets about the trajectory of growth and jobs.8

Overall government expenditure this year as a percentage of GDP is expected to increase from 33 percent to a record high 40.6 percent, according to calculations based on IMF data. (Figure 5) This is significantly larger than the increase following the GFC in 2009.

Unwinding this year’s massive increase in government expenditure will involve difficult choices. The current forecasts assume that regional government expenditure in 2021 will drop from 40.6 to 35.7 percent of GDP. Expectations are that revenue will decline by 2 percentage points this year and barely increase as a percentage of GDP in 2021.

As important as stimulus measures continue to be, economies cannot rely on them indefinitely. Growth is the answer to this challenge, and a coherent framework for growth that provides a sense of direction will be important to managing the transition.

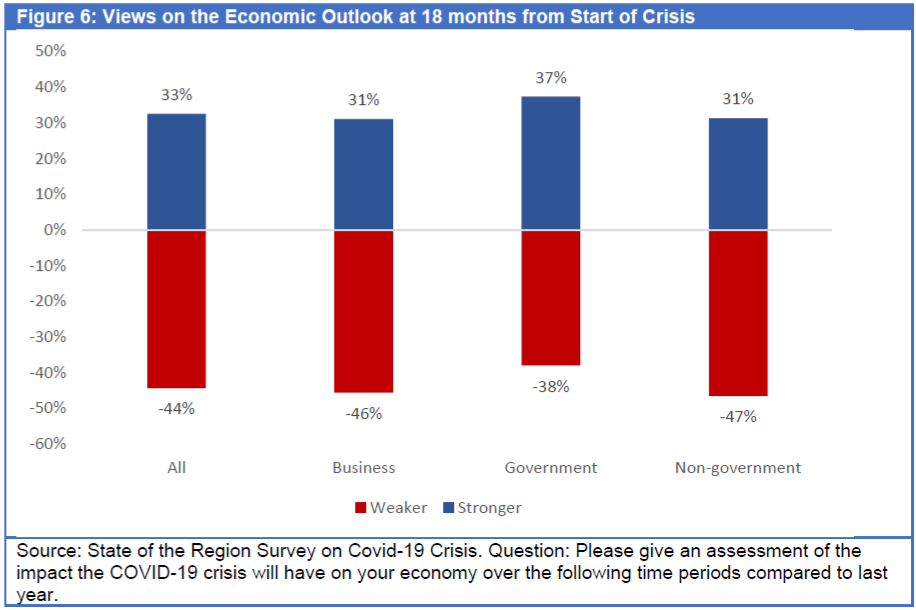

PECC’s survey in May showed divisions on timing of a sustainable recovery: 46 percent of business respondents still expected growth to be weaker 18 months on from the start of the crisis compared to 31 percent who expected stronger growth (Figure 6). This does not bode well for a sustainable recovery, especially as stimulus measures are withdrawn.

Impact on Income Inequality

Covid-19 is impoverishing many people. World Bank estimates suggest the number in extreme poverty (living on less than US$1.90 a day) will increase from 595 million – a number contingent on a relatively swift recovery -- to between 684 million and 712 million.9 Should the worst-case scenario materialize, the pandemic will wipe out all poverty reduction achievements over the past 5 years. The Covid-19 crisis is already having a clear impact on global ambitions to reduce poverty and efforts to make growth more

inclusive.

This exacerbates income inequality in both advanced and emerging economies. The United Nations reports that “income and wealth are increasingly concentrated at the top. The share of income going to the richest 1 per cent of the population increased in 59 out of 100 [economies] with data from 1990 to 2015.”10 While the best way to increase incomes is through increased productivity, the pandemic has come after a long broad-based slowdown in productivity growth following the Global Financial Crisis. A report by the World Bank argues that a pro-active policy approach is needed to boost productivity (and incomes) to facilitate investment in human capital. 11

Amongst the Bank’s recommendations are on-the-job training; upgraded management capabilities; increased exposure of firms to international trade and foreign investment; and enabling the reallocation of resources toward more productive sectors. Of concern are mobility restrictions that slow the reallocation of workers from low-productivity firms and sectors to higher-productivity ones. Often these involved geographic relocation from rural to urban areas – the pandemic may constrain this mechanism.

Deepening inequality also lowers overall growth rates, the OECD estimates that between 1990 and 2010, rising levels of income inequality reduced growth rates for some advanced economies by as much as onefifth. 12 Therefore, there is strong incentive for governments in this low growth environment to address these issues.

The region’s governments have responded to the pandemic with unprecedented fiscal stimulus packages. The World Bank’s report on East Asia and the Pacific Economic Update suggests that some:

“systems of taxes and transfers do not worsen inequality, but they have had relatively little effect on mitigating it….(i)n parallel, there is of course need for expenditure reform, including of subsidies that are not socially desirable.”

There needs to be a deeper discussion about fiscal and social reforms. Some of these issues are not necessarily best suited to regional institutions such as APEC, but many are at least complementary to and supportive of APEC’s goals.

As we argue below, responding to the crisis, and capturing the benefits of cooperation in doing so, is more effective when there is a broad-based of support for an international orientation and recognition of the value of integration. The rise in inequality makes this more difficult to achieve. It risks the creation of disillusionment with an open regime. It creates the apparent basis for an argument to move in the opposite direction, providing an opening for protectionist policies and special interests. Anticipation of this response, and the presentation of practical illustration of the value of openness will be important, not just for stability, but also long-term growth as argued. Communities like those of the APEC leaders and officials with common long-term shared interests have a key role to play in this.

The External Sector

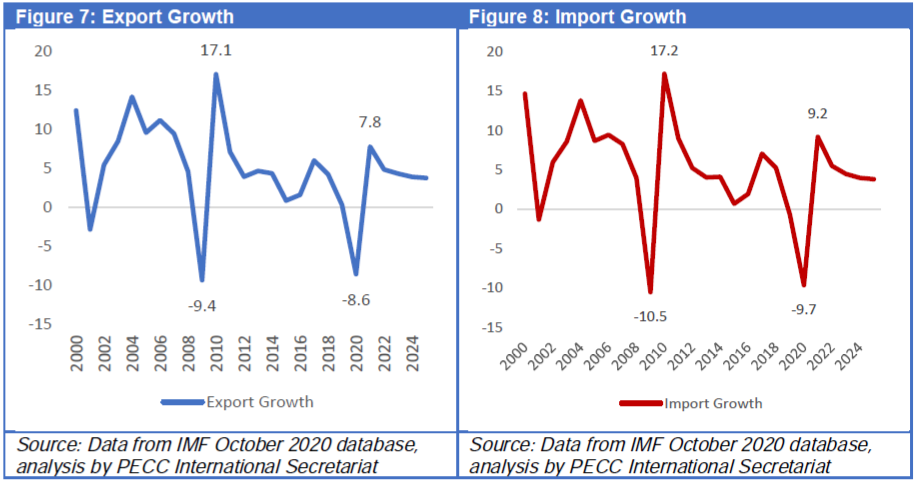

Asia-Pacific exports of goods and services are expected to fall 8.6 percent this year and rebound by 7.8 percent in 2021 (Figure 7). Imports are expected to drop 9.7 percent in 2020 and then grow by 9.2 percent (Figure 8). Notably, the rebound is markedly less sharp than the recovery following the Global Financial Crisis. The IMF said

“Subdued trade volumes also reflect, in part, possible shifts in supply chains as firms reshore production to reduce perceived vulnerabilities from reliance on foreign producers… foreign direct investment flows as a share of global GDP are expected to remain well below their levels of the pre-pandemic decade”.

Moreover, as we discussed in our previous report, protectionism and slowing trade growth have been regarded as risks to growth in our annual survey for a number of years. Their relative importance has also increased over time. As outlined in the sidebar, the multilateral trading system is faced with a number of challenges. Responding to these is a necessary part of the portfolio of policies to restore confidence and stability for a sustainable recovery.

|

Current WTO Challenges and APEC’s Role The Pacific Economic Cooperation Council’s survey on the impact of Covid-19 identified slowing trade growth and rising trade protectionism as the highest risks to growth over the next 2 years after the immediate problems of the pandemic and jobs. This section addresses the challenges facing the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the role that regional cooperation can place in addressing those challenges. The WTO, established in 1994, builds on the collective commitment first made in 1947 in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade to pursue “the substantial reduction of tariffs and other barriers to trade and to the elimination of discriminatory treatment in international commerce” with a view to raising employment and standards of living throughout the world. Through a corpus of some 60 agreements, members together established mechanisms for advancing this goal. First, in successive rounds of multilateral trade negotiations, the WTO has been remarkably successful in reducing tariffs, from around 22% in 1947 to around 5% by the end of the Uruguay Round when the WTO was established, in expanding disciplines on non-tariff measures such as technical barriers to trade and sanitary and phytosanitary regulation, in circumscribing subsidies, including on agriculture, that otherwise distort production and trade, and in adding rules on intellectual property, trade in services, and trade-related investment measures. Secondly, through its councils and committees and its Trade Policy Review Mechanism, the WTO has maintained vigorous surveillance and oversight of member compliance with the rules. Thirdly, the dispute settlement body and its appellate mechanism have been widely used, with over 600 cases filed since 1994, and decisions largely respected and implemented. The WTO has also played a key role in technical assistance and capacity building for developing economies, often in cooperation with bilateral donors and other international organizations. But on each of these fronts, stresses have grown, and many consider the multilateral rules-based trading system to be at risk.

In this context, APEC can be a significant part of the solution. Most importantly, APEC’s tradition of maintaining open and candid discussion at both the officials’ and ministerial levels, and of meaningful engagement with relevant stakeholders through ABAC and PECC, and ASEAN and PIF as sub-regional official observers, is indispensable to building consensus among member economies and beyond. All members should undertake proactive efforts to ensure meetings of Senior Officials, the Committee on Trade and Investment and the Market Access Group, Ministers Responsible for Trade, and Leaders are structured in a manner to foster such discussion. APEC’s track record in leading by example can move multilateral negotiations forward. Its endorsement of efforts to develop a zero-tariff Information Technology Agreement in 1996, and facilitating consensus including between the US and China in 2014 to expand its coverage, led to plurilateral agreement extended to all WTO members on a most-favored-nation basis on a range of products. Similarly, APEC’s pursuit of free trade on environmental goods triggered multilateral discussions at the WTO, still ongoing, and it maintains reporting on APEC’s list of such goods. Looking forward, building on APEC’s non-binding investment principles and Investment Facilitation Action Plan, APEC members can show the way to global agreement. In response to Covid, the APEC Trade Ministers’ commitment “to ensure that emergency measures designed to tackle COVID-19 are targeted, proportionate, transparent, temporary, do not create unnecessary barriers to trade or disruption to global supply chains, and are consistent with WTO rules”, and its Declaration on facilitating the movement of essential goods, is itself a basis for a WTO commitment. As early as 1998, when APEC produced a blueprint on e-commerce, APEC has promoted broader agreement on multiple dimensions of the digital economy. In each of these areas, work can be accelerated and taken to international tables. And APEC members have always considered regional and multilateral trade agreements to be complementary, not competitive. Its Roadmap for APEC’s Contribution to the Realization of the Free Trade Area of Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) provides a strong foundation for pursuing further liberalization on multiple fronts. APEC’s monitoring and surveillance of members’ trade-related policies in a range of fields contributes importantly to transparency and ultimately to compliance with the rules-based trade regime. One specific value proposition that APEC adds is its dialogue on WTO-plus provisions in regional trade agreements. These have covered such difficult issues as those on state-owned enterprises, SMEs and gender. These are issues where bridges and deeper understandings need to be built if progress is to be made at the WTO. APEC’s non-binding nature and emphasis on stakeholder engagement make it an ideal forum for developing that understanding without prejudice to negotiating positions. More generally, APEC’s ongoing attention to MSMEs, accounting for 90 per cent of all businesses in the region, can point the way to how best to modernize WTO rules to be more responsive to their needs. Similarly, the work of the Committee on Trade and Investment and the Economic Committee provides important evidence-based analysis of the relation between trade and investment, competition, and taxation, and the importance of good economic governance at home, including structural adjustment. On dispute settlement, APEC’s Expert’s Group on Dispute Mediation in its report to the Committee on Trade and Investment in 1996 recommended a framework for alternative dispute resolution13, providing Finally, capacity-building and promoting inclusion remains a core APEC competence, further to APEC’s Action Agenda on Advancing Economic, Financial and Social Inclusion, and should continue to be supported by member economies. More broadly, some APEC members are leading by example in foregoing claims of special and differential treatment, better aligning their level of obligation with their level of development, a practice worthy of being adopted by other advanced emerging economies. Jonathan Fried served as coordinator for international economic relations at Global Affairs Canada until August 2020. From 2017 to early 2020 he was Canada’s G20 Sherpa, from 2012-2017, he served as Canada’s ambassador and permanent representative to the World Trade Organization (WTO), where he played a key role in multilateral trade negotiations, including as chair of the WTO’s General Council in 2014 and chair of the Dispute Settlement Body in 2013. He was Canada’s representative to the APEC Vision Group. The views stated here are his own. |

The Covid Context for Regional Economic Integration

Previous editions of this report have laid out the potential economic benefits of region-wide economic integration, which were in the order of US$2 trillion annually.16 These gains would be shared more widely in the region depending on the breadth of the membership and the quality of the agreement. Given the need for growth boosting initiatives after the Covid-19 crisis, a fresh look at the role that trade integration can play in boosting growth needs to be taken.

More recent estimates focus on more specific arrangements under negotiation. For example, work on the economic benefits of Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) estimates not only the potential economic gains for member economies under normal ‘business as before’ circumstances but also should various trade tensions continue.17 With business as before circumstances, the CPTPP and RCEP15 agreements will raise annual global incomes in 2030 by US$147 billion and US$186 billion respectively. Should the trade war continue, global incomes in 2030 will be reduced by US$301 billion, with the trade agreements offsetting that loss by US$121 billion for the CPTPP and RCEP by US$209. Should India rejoin the RCEP the benefits (or offsetting of losses) become larger.

In spite of the entry into force of the CPTPP in 2018 and the likely signing of the RCEP in November 2020, progress towards more extensive integration in the region is challenging because of ongoing trade tensions between the region’s two largest economies, the United States and China, notwithstanding the Phase 1 Trade Deal between them. In the immediate term, the pathway might instead involve the strengthening of the existing agreements, for example deepening commitments in RCEP and extending membership of the CPTPP.

Since the entry into force of the CPTPP several APEC economies have indicated their interest in joining the agreement, notably but not limited to Thailand18. Interestingly, from outside of the region, the United Kingdom has also initiated talks with CPTPP members.19 There is also further positive momentum on the CPTPP with Chinese Premier Li Keiqiang stating that “China has a positive and open attitude toward joining the CPTPP.”20 It is worth noting that at the annual China International Fair for Trade in Services President Xi Jinping’s announced that China would “will continue to work on a negative list system for managing cross-border services trade” which would be a big step towards being able to join an agreement such as the CPTPP.

A major question for the next US administration, regardless of the winner of the November election, is the US position with regards to the CPTPP? A paper by the Asia Society Policy Institute laid out four options:

- Option 1: Returning to the Original TPP

- Option 2: Acceding to the CPTPP

- Option 3: Renegotiating the CPTPP

- Option 4: Pursuing Interim Sectoral Deals

These options are of interest to all current CPTPP members, who are also part of APEC, which thereby has an important role as a platform for engagement between them on issues of mutual concern and which impede more extensive regional integration. This contribution in a non-binding forum has long been APEC’s core, but often discounted, strength.

Returning to the question of the paths to region-wide integration, respondents in the PECC 2019 State of the Region report preferred the option of convergence in terms of product coverage and level of liberalization in various regional agreements. How to do so, and to how to maintain engagement with trading partners in the rest of the word, is another topic that APEC might usefully examine in the coming years.

International Travel

As this update is getting prepared, the resumption of some flights in the region through travel “bubbles” and “green lanes” was underway, a very welcome development. But the overall picture for international travel remained dire. An October update by the International Civil Aviation Organization saw a fall in air passengers (both international and domestic) of between 59% to 62% in 2020, and a 61% drop in revenue.21 The loss in tourism revenue globally this year is estimated at between US$910 billion and US$1.17 trillion, and tens of millions of jobs on the industry had been lost.

In our previous report, we suggested that a critical part of the transition to the post-crisis period is rebuilding confidence in international travel. Progress in making arrangements for reopening travel, like between Singapore and Hong Kong as well as Singapore and Jakarta, shows increased cooperation by governments and provides confidence more travel routes will reopen. However, as the pandemic has not been contained, there is a need to consider more ways of rebooting international travel. The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), representing 45 million companies, has issued a roadmap to restore travel, which includes:

- Recognized standards for testing.

- Accredited testing facilities.

- A standard platform for holding test certificates.22

An important underlying feature of this roadmap is systems that facilitate mutual recognition and trust. As more economies greatly reduce Covid-19 infection rates, the creation of more travel “bubbles” is possible.23 The development of protocols that encourage travel is a worthwhile agenda for regional cooperation. Investment

Last year’s State of the Region report focused on the ‘troubling characteristic’ of the post-GFC period of an ‘inability to move out of the stimulus stance’, noting that capital expenditure had remained disappointing. Even prior to the Covid-19 crisis, expectations had been for an overall contraction in capital expenditure over 2020 and 2021.24

Significant cuts to corporate capital expenditure in reaction to Covid-19 range are likely, and as much as 80 percent according to a McKinsey survey. 25 Doing so frees up cash to deal with the very uncertain business environment. After the primary problem of determining expenditure cuts, the second most cited challenge cited by McKinsey was the “Limited fact base to make decisions to defer or cut”. 26 A framework to help businesses and consumers make forward-looking decisions has value in this context.

The IMF argues that

“the recovery of private sector activity is being constrained by weakened private sector balance sheets, losses in human capital because of unemployment, and skill mismatches as demand shifts from high-contact sectors to those that permit social distancing. Public investment can encourage investment from businesses that might otherwise postpone their hiring and investment plans.”27

Further, the IMF contends that the pandemic

“creates an urgent need for smaller, shorter-duration projects, not only in the health care sector, but also to facilitate social distancing in work and school activities, on transportation, and in public spaces. Such projects include both physical adaptation (for example, greater spacing and transparent barriers) and greater access to digital technologies’

However, the IMF also asserts that public investment will be lower in 2020 than in 2019 in 72 out of 109 emerging markets and low-income developing economies. There is thus an urgent need for governments to work with the business community in rolling out these projects.

FDI Inflow Trends

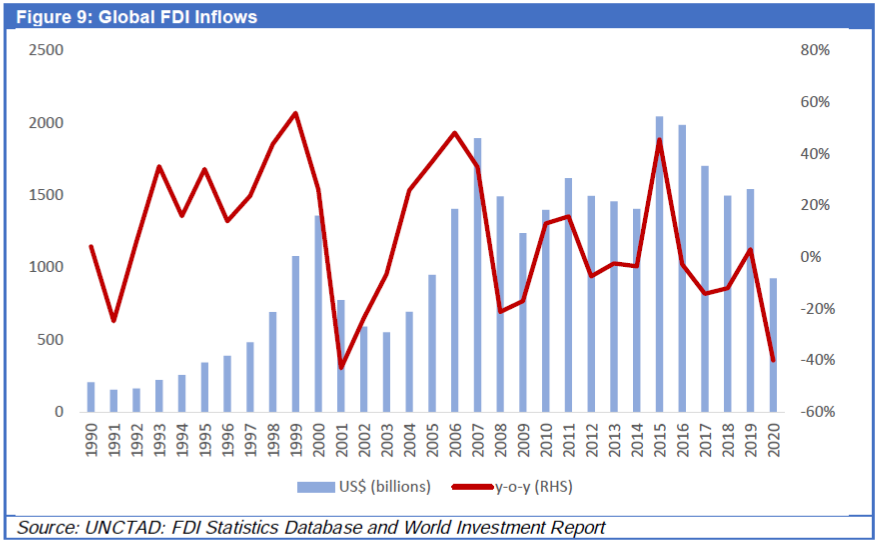

UNCTAD’s World Investment Report forecast a 40 percent drop in foreign direct investment (FDI) flows in 2020. This would bring global FDI inflows below US$1 trillion for the first time since 2009 (Figure 9). The drastic drop in FDI in 2020 can be traced to the pandemic, though UNCTAD argues that FDI has also been reduced due to trade and investment restrictions.

For 2020, UNCTAD forecasts a 30 percent drop in greenfield investment and a 21 percent fall in crossborder mergers and acquisitions. These corporate activities are already badly affected by the significant demand shock and lockdowns, but adding policy uncertainty to this, as a result of concerns over rising protectionism, is likely to leave more money on the sidelines. Regimes applying to FDI have also tightened, as economies seek to constrain foreign takeovers of domestic enterprises affected by the crisis. International law firm Ashurst reports that:

‘since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, certain jurisdictions have tightened their foreign investment regimes... More generally, whether or not specific changes have been introduced, we are likely to see a stricter application of foreign investment regimes for the duration of the current crisis, and potentially over the longer term.” 28

A prolonged shutdown of economic activities will discourage new investment, slows FDI from existing investors and possibly result in divestments. This could affect emerging economies that are highly dependent on foreign investors both for export-oriented industrial activity and in public-private partnership projects in infrastructure development (such as power generation plants and industrial parks).

Looking beyond the crisis, UNCTAD foresees twin pressures on the investment policy environment, asthere could be greater use of restrictive policies but at the same time there is also likely to be competition for investment as part of economies’ recovery plans. Platforms for multilateral cooperation for discussing investment policy then assume greater importance; in 2016, for example, G20 Leaders agreed to the Guiding Principles for Global Investment Policymaking, while APEC has longstanding Non-Binding Principles for Investment. These set a minimum benchmark for dialogue practice that could be taken further.

Digital sector

The picture for growth of the region’s digital sector is mixed. World Intellectual Property Organization’s World Innovation Index 2020 Report argues that compared to the period after the Global Financial Crisis

“…the good news is that the financial system is sound so far. The bad news is that money to fund innovative ventures is drying up. Rather than financing novel, small, and diverse start-ups, venture capitalists began focusing on so-called “mega-deals”—boosting a select number of large firms rather than giving fresh money to a broader base of start-ups.”

The WIPO report point about venture capital targeting mega-deals is of concern for three reasons: small firms have been most damaged by the crisis; there are risks of growing concentration in the sector; and the pipeline for innovation can be damaged.

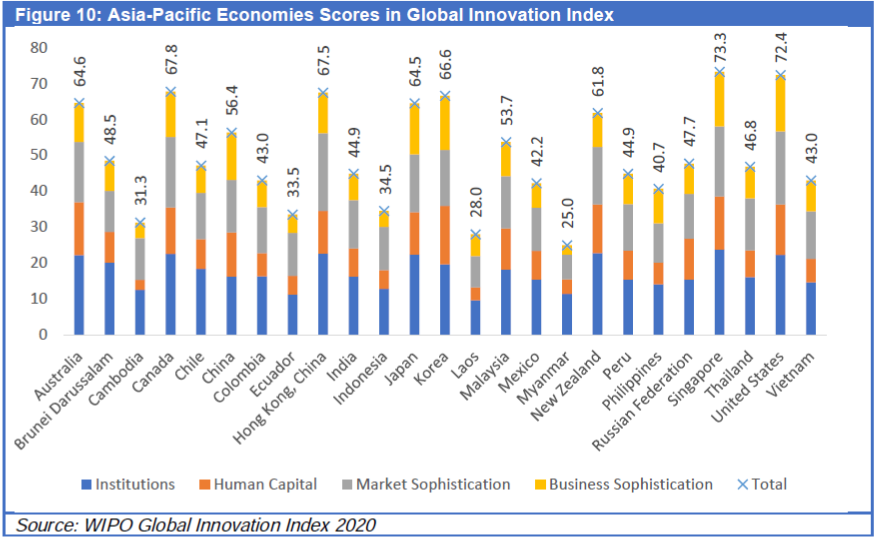

Figure 10 shows selected scores for WIPO’s Global Innovation Index. There is significant heterogeneity across the region in and across the different sub-pillars that should indicate areas where each economy could progress.

Over the years, China, Vietnam, India, and the Philippines have gained the most in the index ranking and are now in the top 50. Given innovative growth is one of the pillars of APEC’s growth strategy, initiatives that focus on improving performance in various dimensions of the index would be one way to improve the region’s overall performance. However, understanding the reasons why the market prefers to invest in larger firms would be a key to channeling funding towards the MSME sector. This points to a need for regional economies to make improvements to the environment for innovation.

The Covid-19 crisis has intensified attention to returns to investment in telecoms infrastructure. GSMA, an industry grouping of more 400 companies reports that the mobile industry delivered a 7% improvement in download speeds during the pandemic, thanks to increased investment in mobile networks, which totaled US$180 billion in 2019. A further US$1.1 trillion is expected to be invested between 2020 and 2025. However, for these investments to materialize to close the coverage gap between those with high speed and reliable Internet and those without, the mobile industry argues that

“governments and regulators need to provide the best possible enabling environment by ensuring

pro-investment and pro-innovation policies that reduce costs and uncertainty around spectrum

allocation and assignments, remove obstacles to network deployment, and adopt international best

practices on tax policy.”29

Some of these enabling policies for the digital economy are identified in WIPO’s Global Innovation Index, others more specific to the telecoms sector are available elsewhere.

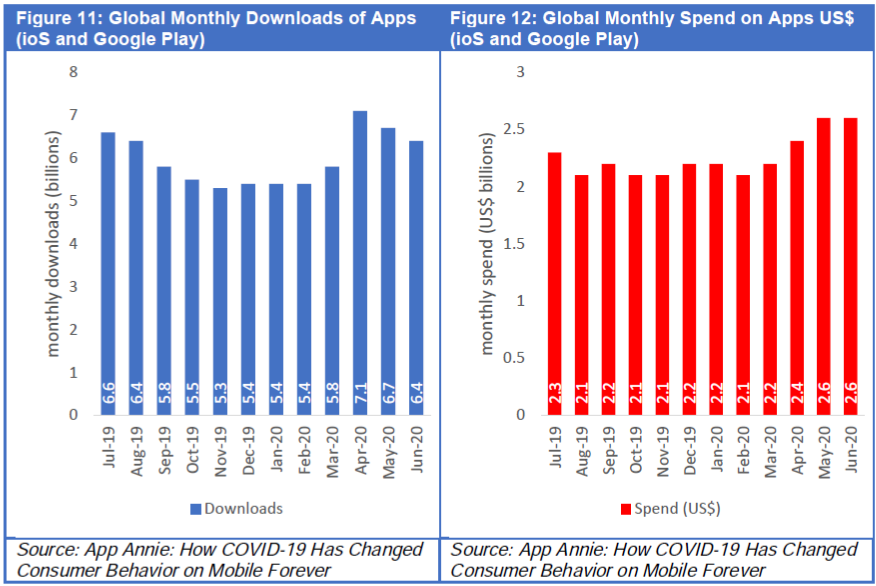

There are several reasons for the changed dynamic in investment in telecoms infrastructure. One is the onset of 5G technology, but a related cause is the acceleration of the use of digital technology caused by the Covid-19 crisis. Downloads of mobile applications exceeded 7.1 billion in April when global lockdowns were at a peak, and global expenditure on applications was over US$2.6 billion.30 (Figures 11 and 12). Importantly, these trends are likely to be sustained after the pandemic has gone, for example, 83% of those shopping online say they are likely to continue spending that way after social distancing restrictions are lifted, according to a study by Bain.31

Expectations that the tech sector will keep growing rapidly are drawing in more funds for investment. US private equity firm KKR recently raised over US$13 billion for an Asia-focused fund, exceeding its US$12.5 billion target. Likely investments will include the tech sector as well as consumer and manufacturing firms.32

The allocation of resources towards more productive sectors faces specific policy challenges. As noted, the digital economy has been critical to enabling effective responses to the pandemic and will be an area of growth for the foreseeable future. However, a lack of regulatory coherence, continued constraints due to the pandemic, rising protectionism and uncertainty about the future of the WTO moratorium on electronic transmissions add up to an environment in which businesses may be unwilling to invest even if interest rates stay near zero.

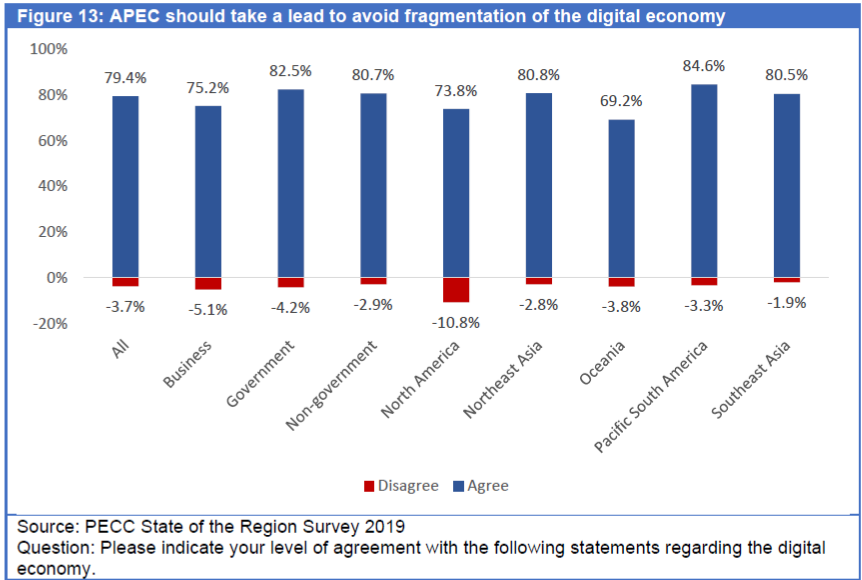

Even before the Covid-19 crisis and the ramped-up demand for digital services, there were deep concerns about the increasing fragmentation of the digital economy. PECC’s survey on the post-2020 vision for the region found extremely broad support across stakeholder groups and sub-regions for APEC to tackle that issue (Figure 13). Understanding why this is important for businesses and consumers alike is critical as well as the drivers of policies behind the fragmentation or the splinternet as it has become popularly known. Given the increased role of the digital economy in light of the Covid-19 crisis resolving those tensions takes on an even higher degree of importance. As discussed in detail in the next chapter, trade agreements are trying to grapple with this issue, but are they fit for purpose?

The Evolution of the Pandemic

One key point in our earlier report was that assumptions for a global economic recovery were based on a belief the pandemic would ebb and containment measures would be loosened in the second half of 2020. Still, there were warnings a second or even third wave was possible. That risk has indeed materialized, though the prognosis for economic growth is largely better than earlier this year.

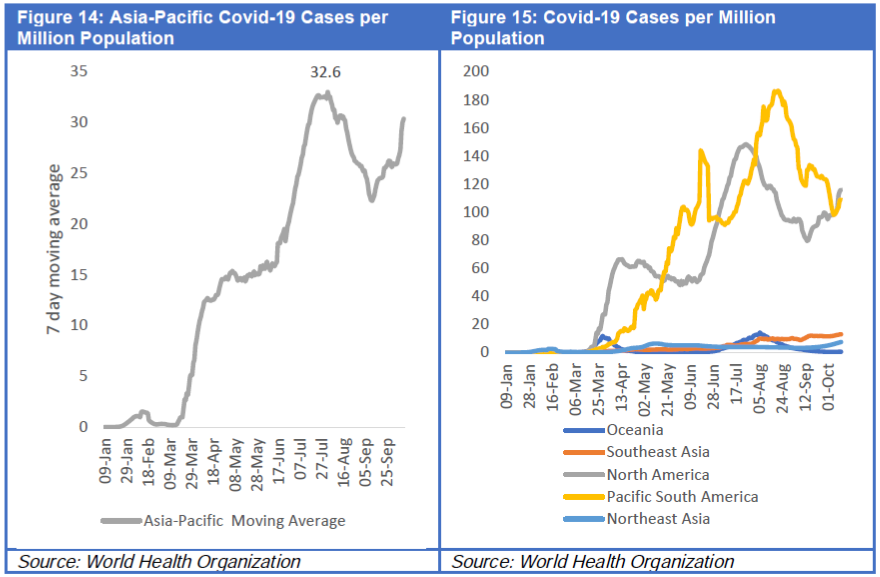

Looking at Asia-Pacific as a whole, the pandemic seemed to have reached a peak of 32.6 infections per million of the population in July before dropping dramatically through August and began to rise again in late September (Figure 14). However, a more detailed look at specific sub-regions and economies shows that infection rates for Oceania, Southeast Asia, and Northeast Asia are at a fraction of North America and Pacific South America levels (Figure 15), and within a sub-region like Southeast Asia, specific economies are faring much better than others

Analysts have been at pains to try to understand the differing performances battling the pandemic. World Bank analysis points out that East Asia and the Pacific sub-regions have, on average, employed more stringent mobility restrictions and done more testing. 33 Their analysis points out that a more stringent lockdown policy has immediate effects in containing the virus while a “smart-containment” policy such as open testing is observed with a lag. Of equal importance but perhaps less well understood is an integrated policy approach:

- Containment

- Testing

- Economic support for lost pay

- Information Campaigns

Without this package, it becomes difficult to gain the political support for policies over a sustained period.34 These approaches have been developed through previous experience with pandemics. One of the variables that seems to distinguish more successful handling of a pandemic is a clear and strong information campaign. A deeper analysis of all of the policies – including how successfully they were implemented - will help future planners learn from the region’s experience with Covid-19.

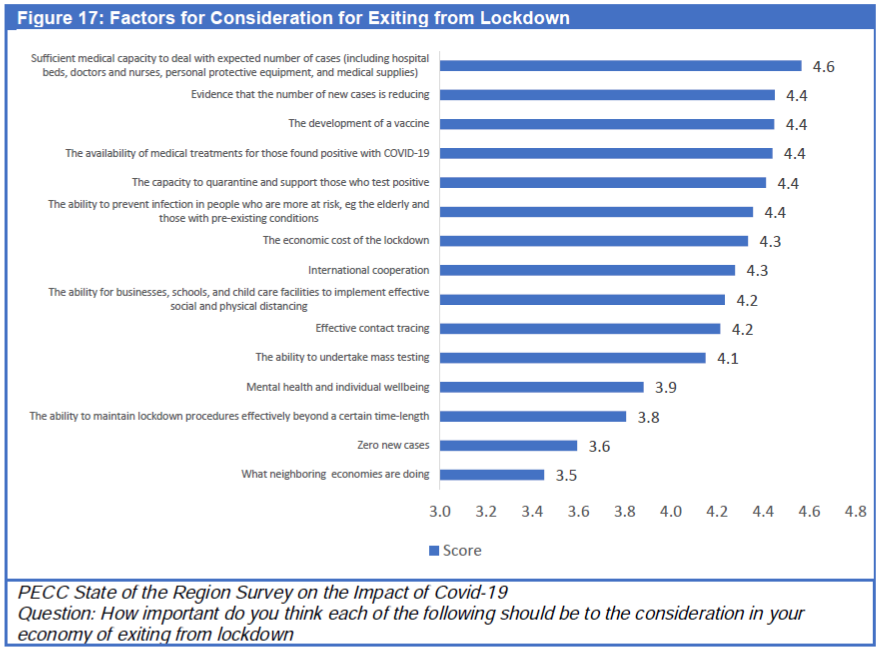

While there are naturally hopes that vaccines can be deployed quickly, the responses to PECC’s survey show the ending of the lockdown was not seen as contingent on that one variable; indeed what was considered as most important was the medical capacity to deal with cases. A vaccine came third in the list, indicating a common view it cannot be available very rapidly.

The Wall Street Journal in October, in an article on how life was largely back to normal in much of Asia, quoted Ashish Jha, dean of the Brown University School of Public Health, as saying:

“If you can control the virus, you can get 95% of your life back … In the U.S. and Europe, we wanted to get our lives back, so we acted as if the virus was under control. In Asia, they were not in denial. They understood they can have their lives back if they follow certain precautions.”

To contain the spread of the pandemic, governments across the region and the world have implemented stringent lockdown policies that have curtailed economic activity, ranging from closing borders, closing schools, stay at home policies and reducing the size of public gatherings.

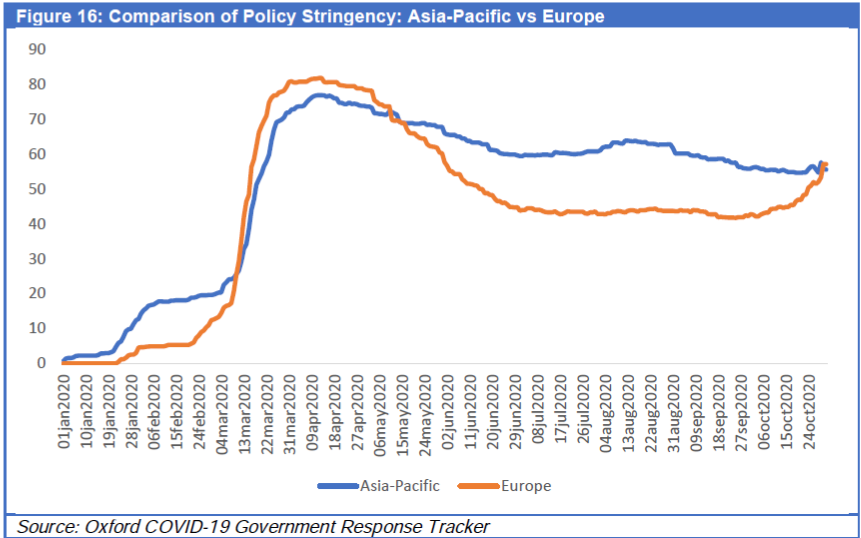

Figure 16 traces the average restrictiveness of those policies since the beginning of the year. The index tracks the level of government policies on school closures; workplace closing; cancelling public events; limits on private gatherings; closing of public transport; stay at home requirements; restrictions on internal movement between cities/regions and restrictions on international travel. As shown in Figure 16, the average level of ‘stringency’ for the Asia-Pacific and Europe since the beginning of the year. As seen in the chart, the level of policy stringency for both peaked in April but declined much faster for Europe. There is no guarantee that the stringency level will not rise again if infection rates increase, for example, parts of Europe have heightened lockdown measures such as imposing curfews and limiting gatherings due to rising infection rates. As seen in the chart the levels of policy stringency for Europe began to climb again at the end of October.

Vaccine development

In May, we asked the regional policy community to evaluate factors to consider for exiting lockdown conditions. The most important were related to medical factors the top 3 being: the ability of the medical system to cope with the number of infections; evidence that the number of infections was going down; and development of a vaccine (Figure 17).

The next step to resolution involves the distribution of vaccines but building the supply chains across multiple modes of transport is a challenge, with respect to the scale of the task and also the policy processes involved.

The WHO estimates that as much as half of vaccines are wasted globally every year because of temperature control, logistics and shipment-related issues.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) estimates that providing a single dose to 7.8 billion people would fill 8,000 Boeing 747 cargo aircrafts. Dealing with these issues might get shipments to the borders of economies, but distributing vaccines to the billions who require them will be an enormous logistical and infrastructure challenge.35 DHL estimates that ensuring global coverage for 2 years would require 15 million deliveries in cooling boxes. Warehouses not designed for medical projects are now being used for medical products, which has led to damage due to inappropriate storage conditions. Different vaccines also require different storage protocols, one of the important factors being storage at temperatures ranging between minus 18°C to minus 80°C. Moving the “last mile” in places where infrastructure is lacking and it is the hardest to meet requirements for special equipment and training36. It is estimated that supply chains account for nearly 25 percent of pharmaceutical costs and more than 40 percent of medical-device costs37.

On top of these physical issues, customs clearance matters, such as supplier certification, have become a problem. Lessons to be learnt here include the need for greater emphasis on reaching agreement on the equivalence of certification processes. Doing so is a longer-term project to build trust among regulators. APEC’s Alliance for Supply Chain Connectivity, which engages the private sector, could be a useful platform for identifying chokepoints in the delivery of vaccines around the region. Before the pandemic, the APEC alliance already had discussed some potential technological solutions to the temperature storage issues that vaccination transportation will pose and the customs-clearance issues that technology will face.

In summary, the development of a vaccine needs to be accompanied by rollout plans that identify potential bottlenecks in distribution and how to address them.

Information Sharing and Minimizing Supply Chain Disruptions

One of the recommendations in PECC’s earlier report was that APEC members should hold a Public- Private Dialogue to explore the creation of a Medical Equipment Market Information System using the G20 Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS). Meanwhile, APEC Trade Ministers agreed to the Declaration on Facilitating the Movement of Essential Goods, in which their economies committed to working together to facilitate the flow of essential goods.

AMIS was a response to the food price crises in 2008 and 2010. It was designed to improve market information about existing stocks. Based on existing structures and resources to avoid increasing costs and duplication of efforts, it consists of three organs:

- The Global Food Market Information Group

- The Rapid Response Forum; and

- The Secretariat

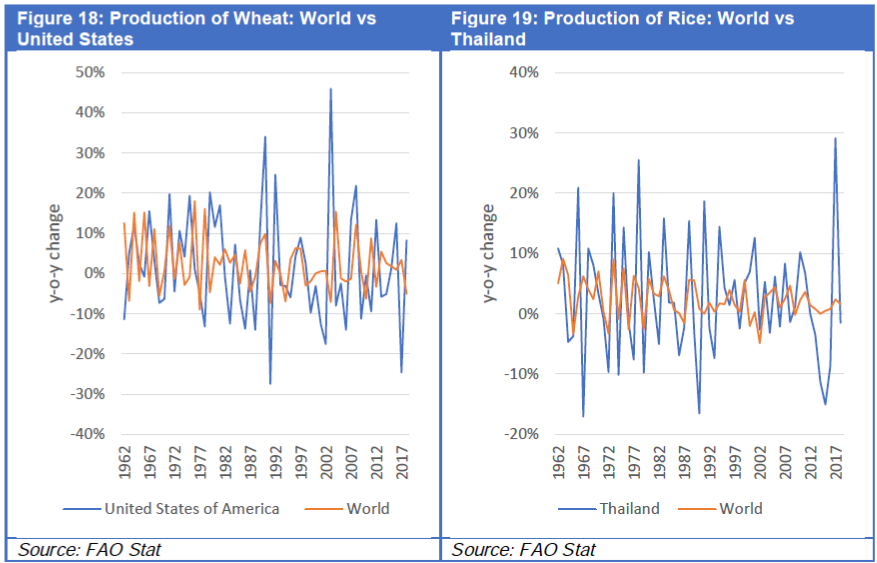

The underlying premise of AMIS is that fluctuations in output at the global level are far smaller than those at the regional or single-economy level. Changes in one region are offset in another. When the global trading system is working, the impact on prices and on volumes is distributed across the world. This is illustrated in Figures 18 and 19 where the variation of the world production of wheat and rice is far less than that in a major producer of each (the United States and Thailand, respectively). Its purpose is therefore to share information across regions, and to avoid inefficient responses to shocks in any one region that might in turn worsen the global situation. An illustration might be the imposition of export quotas following a drought in a large producing economy.

As an evaluation of the funding for AMIS provided by the World Bank points out:

“[t]he turnaround time to design and put together an initiative in response to the food crisis of 2007–2008 was limited - a few months. This led to a situation where the organizations that agreed to form the AMIS Secretariat did not consider who would use AMIS’ outputs and what were the needs of participating countries, in particular the non-G20 ones and more broadly, the entirety of its users.”38

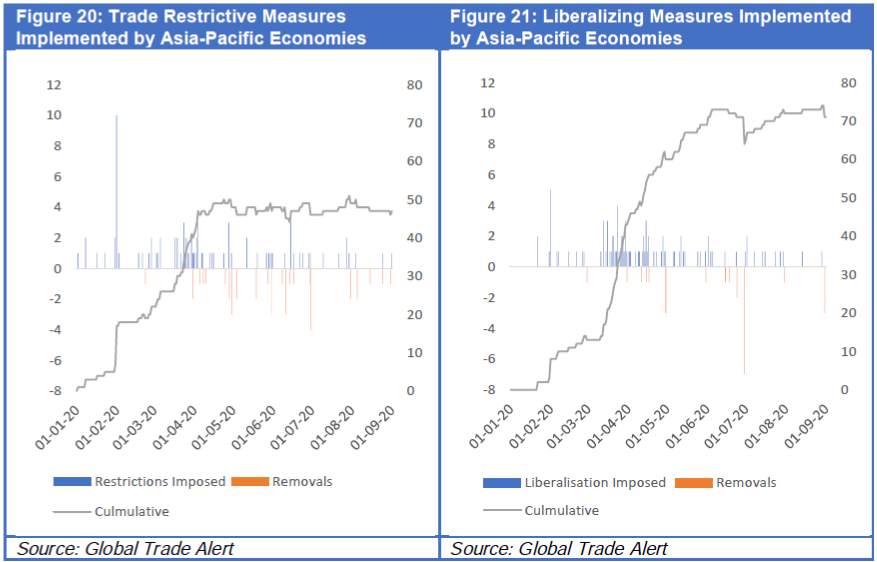

Can this model be translated to medical products, where we also saw the imposition of export controls in anticipation of local shortages? Production of medical equipment is not as vulnerable as crops to the vicissitudes of weather, and as in the Covid-19 case, the changes are more likely to come on the demand side. Even so, the value of an information system remains, at least in principle. To illustrate this point, Figures 20 and 21 are based on data gathered by the Global Trade Alert, the European University Institute and the World Bank to track trade policy measures taken in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. They show the changes in policy for exports and imports of medical and food products during 2020.39

The problem, evident in Figure 20, is that the lack of information or at least opacity in medical goods supply markets can potentially (and indeed did) lead to poor decision-making. The closure of borders as well as factories constrained international production and trade in medical supplies, while the pandemic led to a massive surge in demand. Fear of no access to products led to stockpiling, which exacerbated the issue.

This spurred different policy measures that restricted trade because of a lack of confidence in international markets to supply. At the same time economies were also liberalizing trade – as shown in Figure 21, these include trade facilitation measures to expedite the processing of essential products through customs. However, as “Evenett and Winters (2020) have recently observed, “the benefits derived from lowering import barriers on medical products and medicines during this pandemic are reduced if there is littleavailable to buy at affordable prices as a result of the export bans imposed by trading partners.40”

The original G20 mandate emphasized the key role the private sector plays. Compared to food products, the medical products value chain is populated by a smaller number of large producers. Data from the WTO suggests that, at least for finished products, the top 10 exporters of medical products account for 74 percent of world exports. The model, however, involves the sharing of information along the value chain, which may be constrained by private sector views on the commercial value of that data.

Managing a system like AMIS in this sector means addressing the technical difficulties of dealing with an even more heterogenous set of products. A further challenge for medical products is the complex nature of the value chain. According to Harvard Business Review, for those products, managing a system such as that proposed involves an effort to:

“lay the groundwork by doing advanced planning, analyzing markets to assess the global availability of PPE and ventilator components, and creating sourcing plans for every key need that might arise. To do this kind of planning, it must have abundant, dependable, real-time information from a broad array of sectors on the status of supplies, pandemics, terrorist events, and other unexpected disruptions. And it must be able to validate and integrate this information.”41

Doing so may involve going down into second to third tier suppliers. The world now has a better understanding of what happens during a demand surge, and we need to develop the same visibility on the supply side. Recognizing the differences between food and medicine, the PECC recommendation was to start with a public-private dialogue on the practical question of making this idea work. This is generally a well-tried and utilized Asia-Pacific approach to addressing problems.

There is support for this effort. In PECC’s survey, information on stockpiles of medical supplies was ranked 8th among priorities for regional cooperation. Topping the list were the sharing of pandemic preparedness practices, development of a vaccine, trade facilitation on essential products and the removal of export restrictions on essential products, which survey participants most often rated “very important”. Of activities considered of the second order and “important”, cooperation on medical supply stockpiles was the top priority.

We have made the case for consideration of an information system for medical products, the design of which could be guided by a public-private dialogue. Even if such an initiative proceeded, some governments may still choose, or be unable, to resist domestic pressure to subsidize production, or otherwise tailor procurement that would favor domestic producers. There are, however, constraints on these responses, since in either case, these actions would run into criticism from trading partners and possible disputes that could be taken to the WTO. The defense may be to argue that a special situation exists under Article XX of the GATT, necessary to protect human life or even Article XXI, a security exemption. In this situation, there is also value in a dialogue on the application of these articles.

In summary, there are better solutions than subsidies or distorted procurement regimes that favor domestic suppliers, and information sharing across economies may be a valuable option. The purpose of exploring this option is to:

a) Provide the same if not equal levels of security

b) Reduce costs for consumers

c) Require less government subsidization

d) Do less damage to international markets, if not improve them

Climate Change

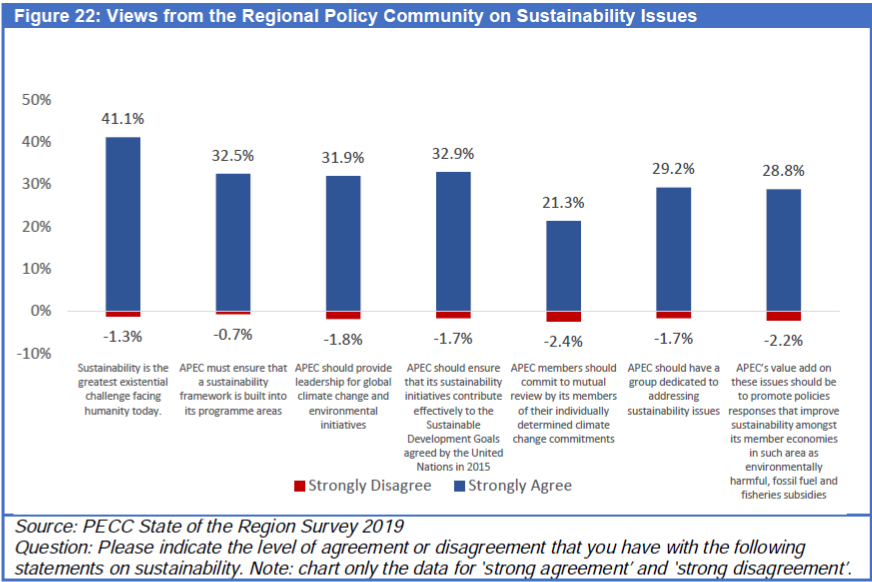

Part of PECC’s recommendation for achieving the post-2020 vision for APEC was “(c)ommitted long term policy initiatives that promote sustainability.” The PECC survey in 2019 found strong support for a number of measures, which was extraordinary, making it difficult to set a priority on which actions might be most useful for a group like APEC to pursue (Figure 22). There was solid support for the general proposition of a threat to humanity, followed by the need for APEC to ensure that sustainability is built into its program areas. There was less support for the idea that APEC economies should review each other’s individually determined commitments but more support for focusing on more practical issues such as environmentally harmful subsidies.

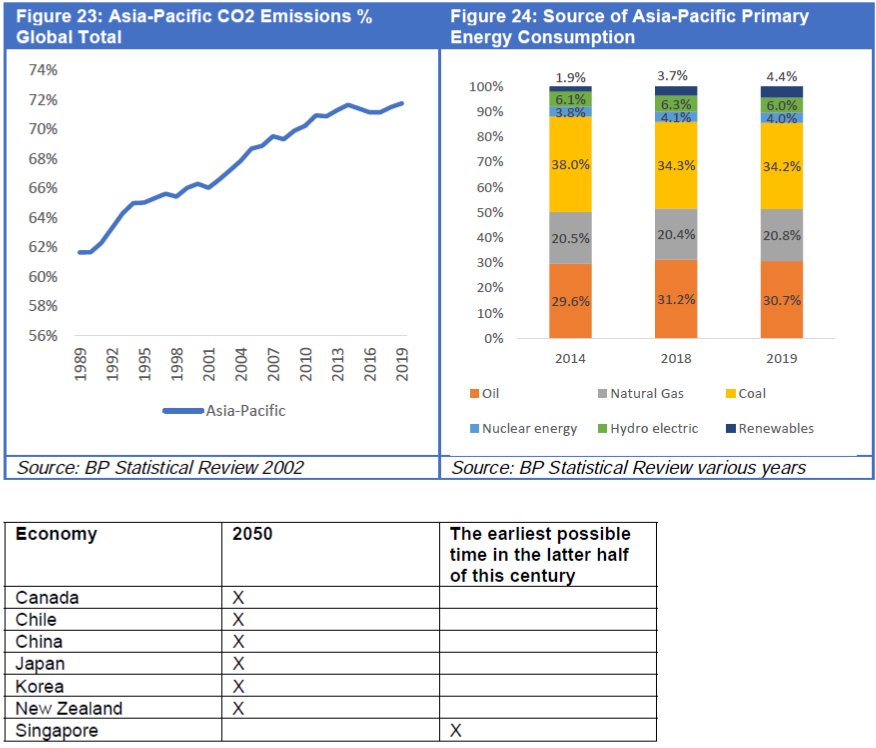

Given the region’s high and rising share of total global CO2 emissions (Figure 23), a solution to climate change without Asia-Pacific ‘on board’ is impossible. Addressing these issues is not new to the APEC agenda, indeed the first APE'C Leaders’ Summit in 1993 envisaged a

“community in which our environment is improved as we protect the quality of our air, water and green spaces and manage our energy sources and renewable resources to ensure sustainable growth and provide a more secure future for our people.”

Since 1993, a number of targets have been set. As part of the APEC Growth Strategy adopted in 2010, APEC economies agreed to

“seek growth compatible with global efforts for protection of the environment and transition to green economies.”

Part of that work included the assessment of the potential for reducing the energy intensity of economic output in APEC economies between 2005 and 2030, beyond the 25 percent aspirational goal agreed to by APEC Leaders in 2007. In 2011, they agreed to further reduce APEC’s aggregate energy intensity by 45 percent by 2035, and in 2014 agreed to double the share of renewables in the APEC energy mix by 2030. The estimated share of renewables in primary energy consumption has already doubled (Figure 24) since 2014. However, the ambitions of APEC members have also increased. At present, 7 out of APEC’s 21 economies have committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions, with 5 out of the 7 committing to that target by 2050 (see table below). Others may choose to join that list. Various forms of regional cooperation can support the effort to reach those goals.

One example of a field of cooperation is the design of infrastructure investment strategies. Economist Nicholas Stern argues that spurring low-carbon growth requires

“the redirection of financial flows and investment in the supporting infrastructure that will form the backbone of economic development, mitigation and adaptation.” 42

Estimates suggest that over the next 20 years, the required investment in infrastructure will be in the region of US$ 100 trillion or more, an average of US$ 5 trillion – US$ 6 trillion per year 43 In short, the argument is that planning would not have us investing in the same models we have been that led us to the current situation. The Covid-19 crisis likely will lead to an even deeper re-examination of the desirability of those trends. As stated elsewhere, people have grown accustomed during the crisis to a working from home model, which changes the dynamics of urban development.44 As earlier discussed, the IMF argues that public investment at this time can also crowd in private sector investment, and this provides a unique opportunity for addressing climate change issues and spurring growth at a critical juncture.

Another area of discussion and cooperation comes at the intersection of sustainability policies and trade policies. For example, the EU Green Deal includes measures to address carbon leakage – a carbon border adjustment mechanism. 45 The language in the European Green Deal specifies that the measure would be designed to “comply with World Trade Organization rules and other international obligations of the EU”. However, WTO rules have not caught up with commercial realities and the WTO itself now lacks a

functioning dispute settlement mechanism.

APEC, working in a crowded field, needs to address some key issues raised in 2009 by the late long time PECC contributor Dr Hadi Soesastro. The first is the need to avoid ‘green protectionism’. The second is the systemic importance of APEC members building confidence between advanced and emerging economies on an often-divisive issue. The recommendation back then was to view the reduction of risk and vulnerability as a key development issue, and to develop cost-effective ways to foster adaptation. It has not changed since 2009.

Efforts in these and other areas are likely to resonate with the business sector. In a survey undertaken in 2018 by the Carbon Disclosure Project of the world’s 500 biggest companies about climate-related risks and opportunities, 225 estimated that the opportunities represented a potential market of over US$2.1 trillion – mostly in demand for low emission products and services, as well as the potential for a better competitive position against shifting consumer preferences coming over the short- to medium-term. In addition, companies expressed the concern that

“Not only does a company need to speak to the efforts they’re making, they also need to show through their actions that they are making improvements or taking mitigation measures. Not

addressing climate change risks and impacts head on could result in a reduced demand for our goods and services because of negative reputation impact,” said Alphabet [the parent of Google].46

In other words, companies not only need to respond to shifting consumer preferences, but they also have to take into account possible reputational damage by inaction.

Finance for Sustainable Development

Attention to issues of sustainability is more evident in financial markets. A report issued to APEC Finance Ministers this year by the OECD notes that Environmental, Social, and Governance (“ESG”) investing has increased dramatically, such that assets under management of institutional investors committing to ESG practices has risen to US$30 trillion globally. However, there is very little clarity of what ESG investing is in practice, and the range of objectives, approaches and metrics that all loosely associated with the term ESG raises attention about the integrity of the investment process.

In a survey of 18 APEC economies that produce guides for listed companies, three main disclosure standards were seen: The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), the Sustainable Accounting Standard Board (SASB) and the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). ESG ratings are at an early stage of development in the region. This represents an opportunity for dialogue and learning from each other’s experience. This work would be valuable in a post-crisis recovery and help provide basic information and metrics that would promote financing for sustainable development.

Conclusions

While recent forecasts for the region’s economic performance in 2020 are less gloomy than earlier ones, growth remains largely contingent on massive government support. Furthermore, the pandemic has not been contained in some places where high infection rates require at least partial lockdowns, blocking any quick economic rebound. The lessons learnt globally for dealing with the pandemic need to be taken on board for a semblance of normality to be restored as the medical community works on a viable vaccine. However, that is only Phase 1 of dealing with the health crisis. Phase 2 -- the rollout and distribution of the vaccine -- needs much more attention.

While it is likely that there will be multiple vaccines on the market, the problems of distribution require the same amount of international attention. A multi-stakeholder approach that identifies chokepoints to distribution is one step in this process. APEC has a long history in identifying chokepoints in supply chains and has a successful track record in working with the business community on these issues.

Our emphasis has been to promote a framework that provides the restoration of confidence. Unfortunately, the current environment does not lend itself to international policy coordination – even though this is a time when that is absolutely crucial. Uncertainty fueled by the pandemic and protectionism is making many businesses cut spending and jobs. The region needs investments that help tackle the digital divide, climate change and inequality. Such investments can nurture sustainable growth – as well as generate both short and long-term dividends.This is important not only for the recovery but for addressing the weaknesses that had characterized growth before the pandemic struck.

One element of this framework is strong support for the multilateral trading system based on agreed values and norms reflected in updated rules and the more effective settlement of disputes. Chapter 2 of this report discusses how the next generation of trade agreements are attempting to create rules for digital trade and whether they are fit for purpose. We addressed the challenges currently facing the WTO. None of these issues are easy to address but importance of addressing them cannot be understated, nor are they insurmountable. The history of Asia-Pacific cooperation is valuable and instructive. At the time of APEC’s formation the world was divided and seemingly facing increasing trade disputes but economies of this region nonetheless did come together in pursuit of a common vision.

International cooperation must play a critical role in the later-pandemic and post-pandemic periods. The current economic environment is one of great uncertainty, and uncertainty is one of most important inhibitors of robust growth.

1 The definition of Asia-Pacific in this report is broad, including the members of APEC, PECC and the East Asia Summit.

2 The forecasts contained here are largely based on the International Monetary Fund’s October World Economic Outlook

3 https://www.pecc.org/resources/publications/regional-cooperation-1/2608-pecc-apec-2020-vision

4 https://www.apec.org/Publications/2019/05/APEC-Regional-Trends-Analysis---APEC-at-30

5 https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/asia-pacific/asias-future-is-now

6 https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/10/06/sp100620-the-long-ascent-overcoming-the-crisis-and-building-a-moreresilient-economy

7 Fiscal Monitor April 2020, “Policies to Support People During the COVID-19 Pandemic”, accessed on 7 July, 2020,

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2020/04/06/fiscal-monitor-april-2020

8 Michelle Jamrisko and Gregor Stuart Hunter, “When $8 Trillion in Global Fiscal Stimulus Still Isn’t Enough”, Accessed on 1

May 2020, https://www.bloombergquint.com/china/when-8-trillion-in-global-fiscal-stimulus-still-isn-t-enough

9 https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/updated-estimates-impact-covid-19-global-poverty. We also note that in some economies in which social security systems have been deployed in stimulus packages then poverty rates could fall: see for example the case of the United States in https://www.economist.com/united-states/2020/07/06/americas-huge-stimulus-ishaving-surprising-effects-on-the-poor

10 https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/02/World-Social-Report2020-FullReport.pdf

11 World Bank, Global Productivity: Trends, Drivers, and Policies, 2020:

https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/publication/global-productivity

12 Federico Cingano, Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth, OECD, 2014.

13 Dispute Mediation Experts’ Group Reports on a Voluntary Consultative Dispute Mediation Service, 35 I.L.M. 1102 (1996); see also the 1998 Committee on Trade and Investment Annual Report to Ministers, APEC#98-CT-01.1

14 APEC#99-CT-03.2

15 https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds488_e.htm; WTO, Indonesia – Safeguard on Iron or Steel Products, Understanding Between Indonesia and Vietnam Regarding Procedures Under arts 21 and 22 of the DSU (27 March 2019) WT/DS496/14, para 7; WTO, Indonesia – Safeguard on Iron or Steel Products, Understanding Between Indonesia and Chinese Taipei Regarding Procedures Under arts 21 and 22 of the DSU (15 April 2019) WT/DS490/13, para 7, see also

https://tradebetablog.wordpress.com/2019/08/21/bother-at-wto-court/#noappeal

16 These benefits refer to modelling of a scenario of the Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP). See https://www.pecc.org/state-of-the-region-report-2014

17 https://www.piie.com/system/files/documents/wp20-9.pdf

18 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cptpp-thailand-idUSKBN23I1PM

19 https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-takes-major-step-towards-membership-of-trans-pacific-free-trade-area

20 http://english.www.gov.cn/premier/news/202005/29/content_WS5ed058d2c6d0b3f0e9498f21.html

21 https://www.icao.int/sustainability/Documents/COVID-19/ICAO_Coronavirus_Econ_Impact.pdf

22 https://iccwbo.org/content/uploads/sites/3/2020/10/tourism-ministers-letter-061020.pdf

23 https://www.mot.gov.sg/News-Centre/news/detail/singapore-and-hong-kong-reach-in-principle-agreement-to-establishbilateral-air-travel-bubble

24 https://www.pecc.org/state-of-the-region-reports/282-2019-2020/847-chapter-1-asia-pacific-economic-outlook

25 https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/capital-projects-and-infrastructure/our-insights/resetting-capital-spending-in-the-wakeof-covid-19

26 Ibid

27 IMF Fiscal Monitor October 2020, Chapter 2 - Public Investment for the Recovery,

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2020/09/30/october-2020-fiscal-monitor

28 https://www.ashurst.com/en/news-and-insights/legal-updates/global-foreign-investment-control-regimes---changes-in-light-ofcovid-19

/

29 2020 Mobile Industry Impact Report: Sustainable Development Goals:

https://www.gsma.com/betterfuture/2020sdgimpactreport/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/2020-Mobile-Industry-Impact-Report-SDGs.pdf

30 https://www.appannie.com/en/insights/market-data/covid19-consumer-behavior-mobile/

31 https://www.bain.com/insights/how-covid-19-is-changing-southeast-asias-consumers/

32 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kkr-asia-fundraising-idUSKBN1XH1RF

33 From Containment to Recovery: Economic Update for East Asia and the Pacific, October 2020,

https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eap/publication/east-asia-pacific-economic-update

34 Ibid

35 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/sep/10/we-have-too-few-planes-to-deliver-any-covid-19-vaccine-warns-aviationgroup

36 https://www.dhl.com/global-en/home/insights-and-innovation/thought-leadership/white-papers/delivering-pandemicresilience.html

37 http://mddb.apec.org/Documents/2020/CTI/A2C2/20_cti_a2c2_009.pdf

38 http://www.amis-outlook.org/fileadmin/user_upload/amis/docs/resources/WB%20evaluation.pdf

39 The problem identified by this initiative is that ‘governments often announce to the media changes in their trade policies before publishing official decrees and implementing regulations and in advance of notifying the World Trade Organization.’ Moreover, the total of trade restrictions picked up by this initiative are significantly higher than those reported to the WTO.

40 Cited in Richard E. Baldwin and Simon J. Evenett, COVID-19 and Trade Policy: Why Turning Inward Won’t Work https://www.globaltradealert.org/reports/download/53

41 https://hbr.org/2020/09/why-the-u-s-still-has-a-severe-shortage-of-medical-supplies

42 http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/728181464700790149/Nick-Stern-PAPER.pdf

43 https://www.brookings.edu/research/driving-sustainable-development-through-better-infrastructure-key-elements-of-atransformation-program

/

44 http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/728181464700790149/Nick-Stern-PAPER.pdf

45 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1576150542719&uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN

46 https://www.cdp.net/en/research/global-reports/global-climate-change-report-2018/climate-report-risks-and-opportunities